The New People’s Army – The Communist Insurgency in the Philippines

The following is a five part series looking at the Communist insurgency being conducted by The New People’s Army in the Philippines and how it developed in 2017. The series is broken up as follows:

Part 1: released 22nd Jan 2018.

The Philippines in 2017.Methodology.The New People’s Army. Fighting Environment.

Part 2: released 23rd Jan 2018.

The NPA’s Activity in 2017. Jan – Jun 2017.

Part 3: released 24th Jan 2018.

Jul – Dec 2017.

Part 4: released 25th Jan 2018.

Arson Attacks. The Use of Explosives.

Part 5: released 26th Jan 2018.

The Year Ahead.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Part 1: released 22nd Jan 2018.

The Philippines in 2017.

Intelligence Fusion recorded over 6,000 security incidents in the Philippines over the course of 2017. These incidents for the most part revolved around President Duterte’s war on drugs, common crime, and the activities of non-state armed actors including the Abu Sayyaf Group, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters, the Maute Group, the Ansar Al-Khilafa group, and the New People’s Army.

In regard to the war on drugs, international and national headlines revolved around the high number of deaths of suspects and users at the hands of security forces and vigilantes. This high number led to demonstrations in the Philippines and criticism from abroad that pushed President Duterte to take the Philippine National Police (PNP) force away from combating drugs, and letting the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) take the lead. While by the end of 2017, the PNP had rejoined the efforts, there was a decline in the number of deaths attributed to the operations of security forces under the leadership of the PDEA. However, the deaths attributed to vigilantes stayed steady throughout, and will be a problem that will need to be addressed strongly in 2018. These vigilantes for the most part kill drug users or suspects in the drug trade by doing drive-by killing on motorcycles. For the most part, activities related to the war on drugs were concentrated in Metro Manila, Cebu City, and Bacolod City, similar to the incidents of common crime recorded by Intelligence Fusion.

Besides the war on drugs and common crime, the activities of Islamic militants and communist rebels caused the biggest problem for the government and the Armed Forces of the Philippines. The first few months of the year saw, predominantly, activity from the Abu Sayyaf Group concentrated in Basilan and Jolo Islands in the Sulu Archipelago. While the groups activity has remained fairly constant throughout the year, March and April saw the rise in the number of incidents attributed to another Islamic militant group, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters, primarily located in Maguindanao. The groups activity has not been as steady as Abu Sayyaf, but the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018 saw a rise in attacks with improvised explosive devices on their part. Despite the two aforementioned groups’ activity, international media’s interest in the activity of Islamic militants in the Philippines significantly grew at the end of May when the Maute Group, an Islamic militant group based in Lanao del Sur, took control of Marawi City. The group managed to retain control of large swaths of the city for 5 months, resisting near daily bombardments by government planes and artillery. The siege led to the deaths of over 150 soldiers, wounding more than 1,000 others, and furthermore killed dozens of civilians.

The siege was a significant scale up from the attacks that had been perpetrated by any non-state armed actor since the beginning of the year. Furthermore, it showcased the weaknesses that the Armed Forces of the Philippines have, particularly heir inexperience in urban warfare. Soldiers that had been fighting for years in jungles, were now faced with narrow streets, sniper fire, and a high number of improvised explosive devices, which led to a high casualty count for the government troops. Of additional significance was the imposition of martial throughout Mindanao the day after fighting began. Martial was not well received a large portion of the population and other armed groups such as the New People’s Army. In December 2017, martial law was extended until December 31st, 2018 in Mindanao.

While Islamic militant groups pose a significant threat to the Philippine’s national security and receive the better part of international media coverage due to the current global security climate, a group that has been active for over close to 50 years in the country and poses a similar threat, is the New People’s Army. Their activity in 2017 continued to be nationwide and have an impact on the policies of the government and the lives of civilians. The following report takes a deeper look at the group’s methods and activity over the past twelve months.

Methodology.

The following report is a look back of the activities of the New People’s Army in 2017. The basis for the analysis stems from collecting and mapping 693 incidents over the course of 12 months. The incidents were collected through local and international news sources, the websites and social media accounts of the parties involved in the conflict, and the social media accounts of other sources, primarily local journalists sharing information through Twitter. While the author has collected these incidents, it is by no means a complete dataset, as there are likely incidents that have occurred that may not have been recorded on any platform the author has access to. Additionally, there are incidents that may have occurred that may not have been attributed to a group mentioned in this report, and should have but for a lack of detailed information on open source platforms.

The data is divided into 20 categories: Arrest, Arson, Attack Helicopter, Close Quarter Assassination, Grenade, Improvised Explosive Device (IED) Detonation, IED Find, Infantry, Kidnap, Other, Security Operations, Skirmish, Small Arms Fire, Statement, Surface to Air Fire, Surrender, Theft, Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)/Mine, and Weapons Trafficking. These categories, for the exception of ‘Surrender’ are the same as those used on the Intelligence Fusion platform. The decision for the additional category of ‘Surrender’ was that rebels who surrender to authorities, while detained by them, are later released and reintegrated into normal civilian society, and therefore did not match with any other incident categories. Incidents are categorized by the author of this report, and is done so by what the author believes is the most significant aspect of the incident. This means that some incidents categorized as one thing, could also fit in another category (i.e. a skirmish which leads to significant find of explosives, may have been categorized as an ‘IED Find’ rather than a ‘Skirmish’). Moreover, some incidents may have been deconstructed and put into two or more categories (i.e. a skirmish between government troops and rebels would have been categorized as a ‘Skirmish’, but if government troops also used attack helicopters during the clash to launch airstrikes at the same time then the incident will also be mapped under ‘Attack Helicopter’. The occurrence of this is minimal, and is only done so when an incident has two or more significant parts.

The New People’s Army.

The New People’s Army (NPA) was founded in 1969 by Jose Maria Sison and Bernabe Buscayno, and serves as the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines which was founded in 1968 by Sison. Due to the relationship between the political party and the armed wing, they are often referred to as one, the CPP-NPA. Since its founding, the group has been waging an armed insurgency in the hopes of changing the leadership of the Philippines to favor the working class, and expel U.S. influence from the country. The ideology reflects earlier activities undertaken by Sison as a student activist who organized boycotts, and led a guerilla army to fight Japanese and U.S. colonialism and the Filipino elites, as part of the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP). The PKP, which was later banned, was the jumping point for Sison to create the CPP after he was forced out due to speaking against its leaders.

Since its beginnings, the CPP-NPA has been run on the Maoist ideology of protracted people’s war, which aims to maintain the support of the populace, while drawing the government into the countryside and fighting them using guerilla style warfare. This warfare involves making the most of its environment, hiding in jungles, caves, and the mountainous areas of the Philippines to attack and evade government forces. To maintain the support of the public, the CPP-NPA has avoided civilian targets and casualties when possible, and primarily targeted government forces, those who they consider sympathizers of the government, and those who go against their beliefs such as drug suspects. Additionally, large local and multinational corporations have been the target of arson attacks by the group, as they are seen to be an antagonist to the way of life of smaller scale farmers and workers whom the CPP-NPA derives its power from. Moreover, authorities say that these corporations also get attacked if they refuse to pay the NPA’s ‘revolutionary tax’, which helps fund the NPA’s war against the government. The Defense Secretary of the Philippines, in July 2017, revealed that the NPA can obtain P1.2 billion ($23 million) each year from extortion activities, in Eastern Mindanao alone. The methods of the CPP-NPA have allowed them to survive and be able to wage a campaign against the government for close to half a century.

The Government of the Philippines and the communist insurgents have engaged in peace talks for several decades, but the talks have yet to bear fruit. During these talks, the CPP-NPA negotiate under the banner of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines, which is a coalition of organisations with progressive social and economic causes, trade and agricultural unions, indigenous groups, and leftist political parties, among others. The umbrella that it provides for the CPP and NPA leads to the groups sometimes referred as one, as the CPP-NPA-NDFP. The most recent significant success of the group was the ceasefire agreed to by both sides in August 2016. However, the ceasefire broke down in the first months of 2017, leading to an uptick in violence between both parties.

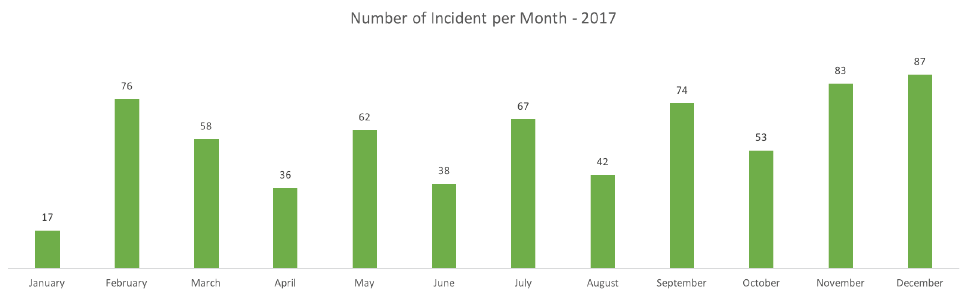

The above graph represents the number of incidents recorded by Intelligence Fusion regarding the activity of the communist insurgency in 2017. (Click on above image to expand)

Fighting Environment.

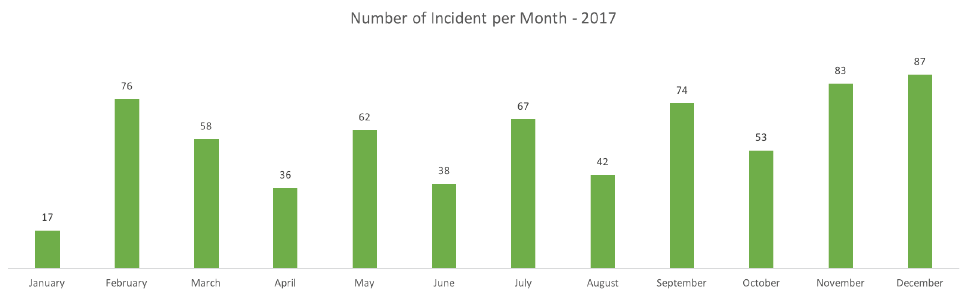

The Philippine archipelago is made up of over 7,000 islands, and has a total land cover of close to 300,000 square kilometers. Due to the country’s position in the Pacific Ring of Fire, the islands are volcanic in nature and are for the most part mountainous. This environment has been of great advantage to the New People’s Army in its fight with the government. The guerilla tactics used by the NPA aim to draw the government forces into the hills, mountains, and jungles of the Philippines to have the upper ground during assaults, have tree cover to be able to avoid being targeted by air strikes, in addition to having cover to retreat when needed. This environment is congruent to a strike and run mentality which has been successful in keeping the NPA fighting for over four decades. The map below shows the areas where the NPA has been most active in 2017 showing that they have been active in all three island groups: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. Additionally, each circled area on the map is on or near hills or mountainous area, confirming the NPAs tactics of using the highlands as bases of operations to launch ambushes and engage government troops. While the terrain is an advantage for the rebels, it is also not without hardships. The living conditions, particularly in the rainy season, has been cited by surrendering rebels as one of the reasons for their return to the law.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Part 2: released 23rd Jan 2018.

The NPA’s Activity in 2017.

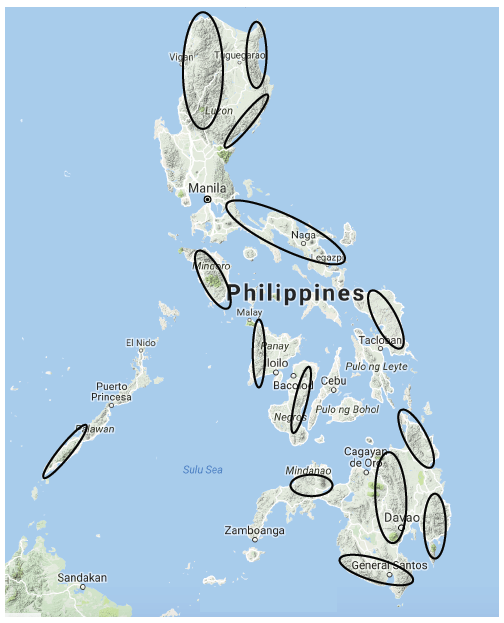

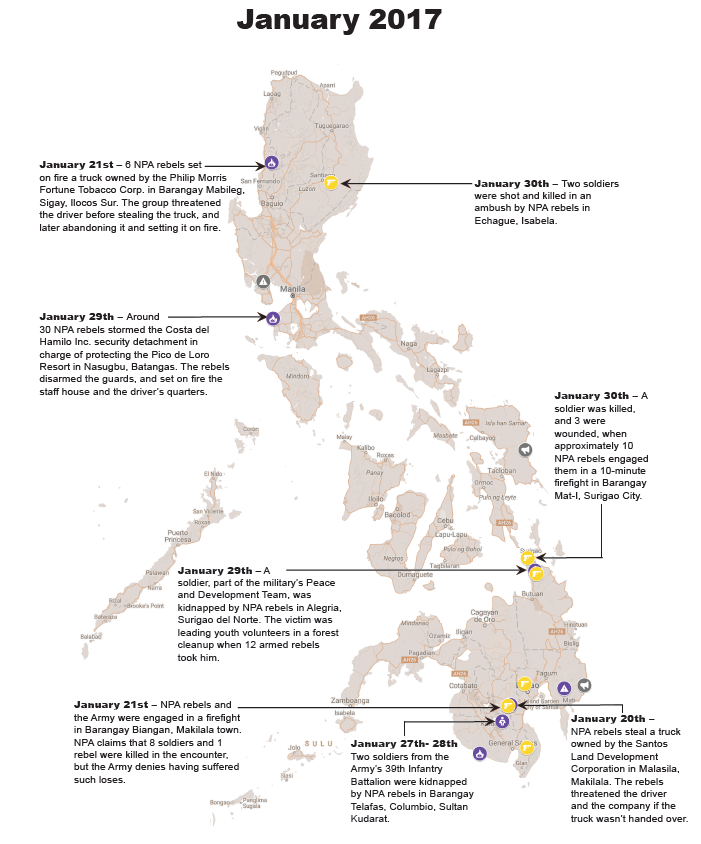

The year started off calm, with peace talks scheduled in Rome between the NDFP and the Government of the Philippines’ negotiators from January 16th through 25th. However, the security situation started to deteriorate around the same period, as the talks led to no significant progress being made, particularly regarding the government releasing close to 400 prisoners. The resumption of hostilities was seen with skirmishes, small arms fire, thefts, and kidnappings in Mindanao, as well as arson attacks in northern Luzon. The deadliest clash between rebels and government forces took place on January 21st, where 8 soldiers and 1 rebels were killed. The Army has denied that it suffered that many casualties. However, January 30th saw the most incidents with nine coordinated attacks nationwide. The frequency of incidents that took place in the second half of January, during the Rome Peace Talks, only increased in February.

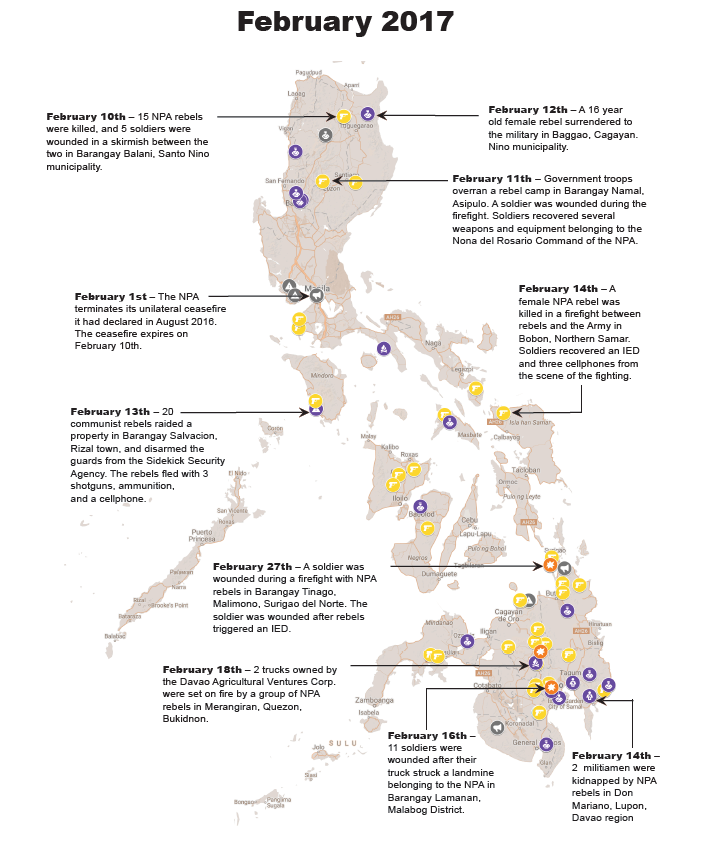

On February 1st, the NPA announced it would be terminating its unilateral ceasefire, and the move would take effect on February 10th. The unilateral ceasefires had been signed by both parties on August 26th, 2016, and in the period between its signings and the beginning of 2017, there had been very few incidents involving the groups. However, in November of 2016, the NPA has threatened to terminate the ceasefire due to the deployment of government soldiers in areas under NPA control. A couple days after the groups termination of the ceasefire, President Duterte undid the government’s ceasefire himself, allowing military operations to resume full fledge against the rebel group. With both parties doing away with the ceasefires, the month saw a significant spike in the incidents recorded (from 17 in January to 76 in February). Out of the 76 total incidents recorded that month, 29 were skirmishes, representing the highest number of clashes per month in 2017.

January – February 2017

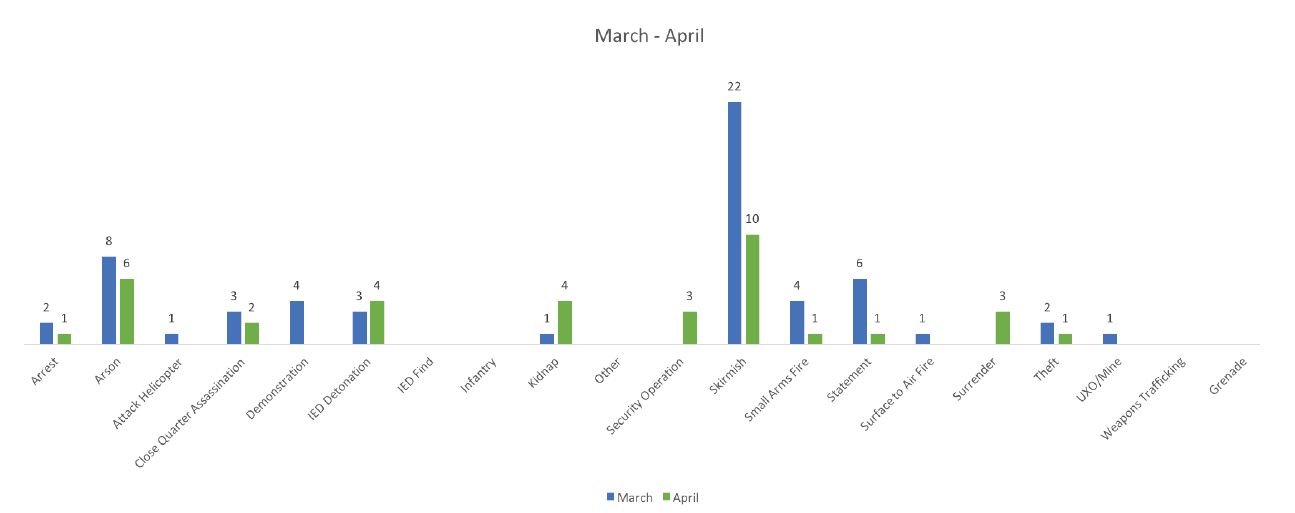

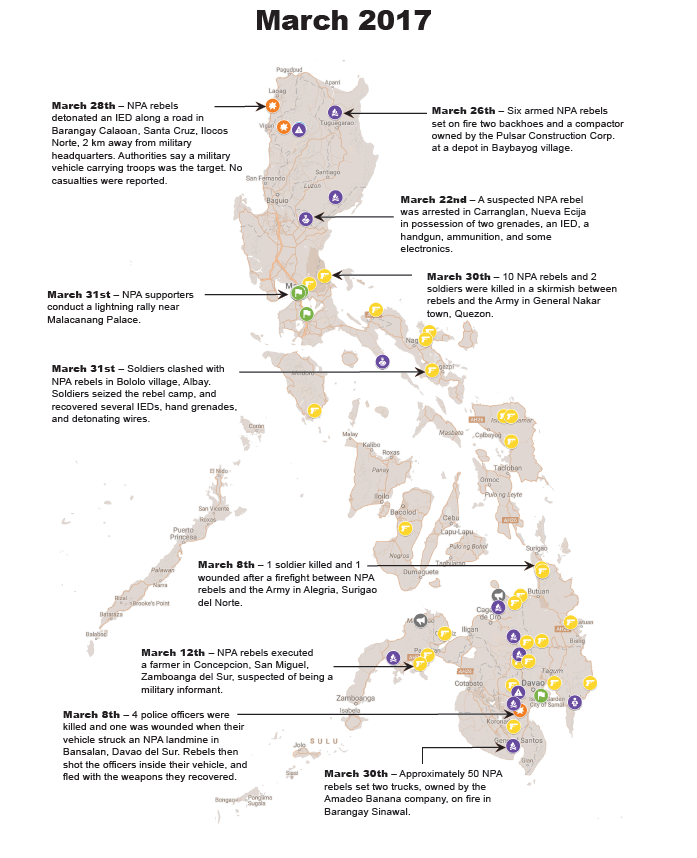

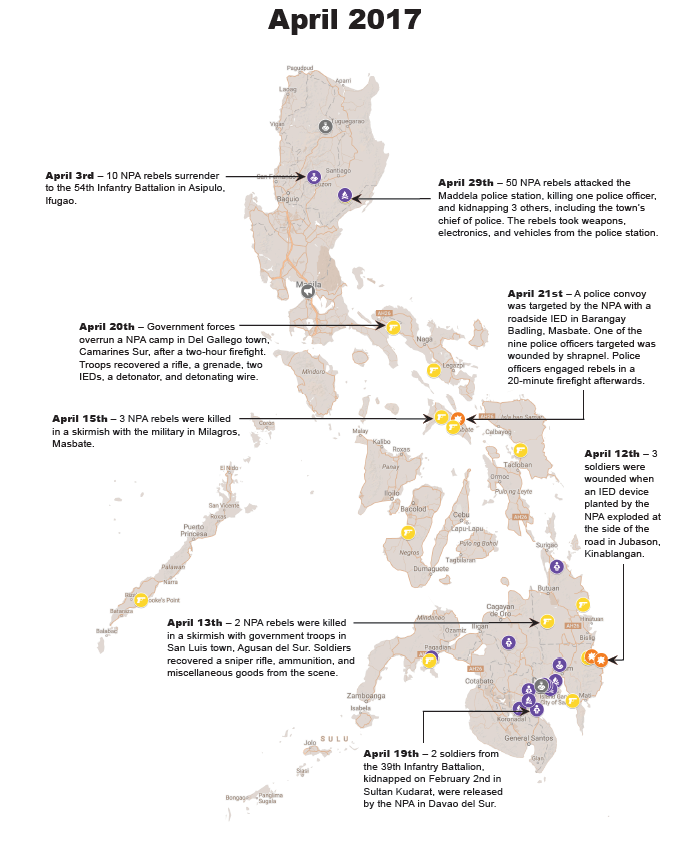

March – April 2017

The spike in incidents that was observed from January to February decreased in March through April. This downward trend can be attributed in part to the back-channel discussions between NDFP and government negotiators on March 10th and 11th in Utrecht, Netherlands. Their discussions led to both sides agreeing to continue formal peace talks, and to reinstate their unilateral ceasefires. However, the ceasefires never materialized as hostilities continued, and the government backed out of implementing theirs, in turn leading to the CPP-NPA to not put theirs in place either. Nonetheless, both sides met again in April in the Netherlands for the fourth round of peace talks, and on the 5th of April agreed on a joint unilateral ceasefire. The agreement would allow both sides to discuss other issues such as the collection of revolutionary taxes by the NPA, the strength of both side’s forces, and the release of political prisoners. However, like the times before, the ceasefire did not hold, and hostilities would begin to increase once more.

Of significance in this two-month period was the Communist Party of the Philippines’ celebration of the 48 years of existence of the New People’s Army on March 29th, and the days before, during, and after saw multiple lightning rallies being held in Manila, Quezon City, Calamba City, and Davao City to commemorate the day. Additionally, the day was marked by announcing that the CPP held its Second Party Congress in October and November of 2016, and had elected new members to its central committee and political bureau, with a special focus on young and middle-aged cadres being elected. The central committee is the highest policy-making body within the CPP, and the election of young members will allow for new leadership to guide the party for future generations.

Whilst the political side of the communist insurgency held lightning rallies, attacks carried out by the NPA continued nationwide, with an increase from earlier in the year in the areas of Samar, Northern Samar and Masbate. Also on an upward trend was the use of improvised explosive devices by the group in its attacks on government soldiers. A significant incident during this period was the coordinated attacks near Davao City of several facilities of the Lapanday Foods Corporation, of the Macondray Plastic Factory, and of the Lorenzo Ranch. The attacks on April 29th led to significant damage to the facilities and the theft of weapons from security guards, but no casualties were recorded.

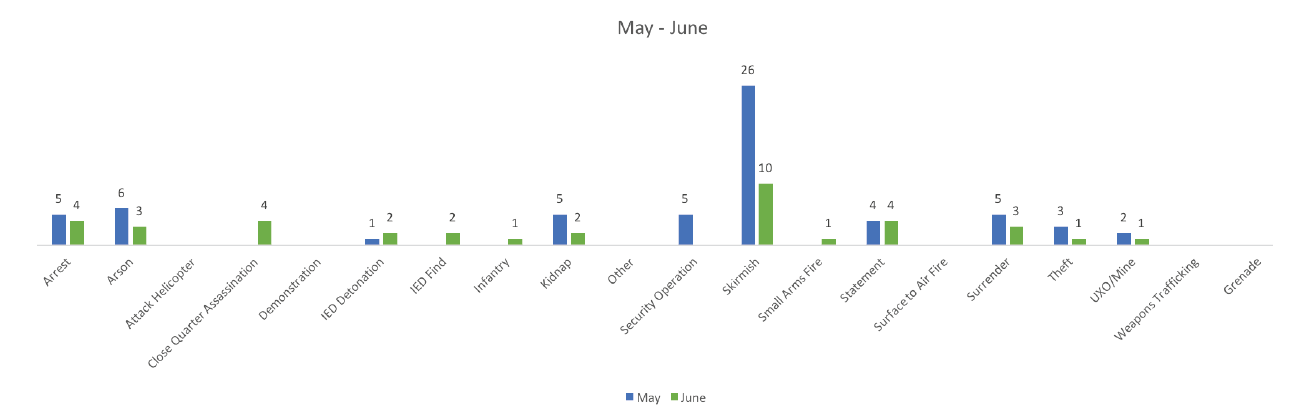

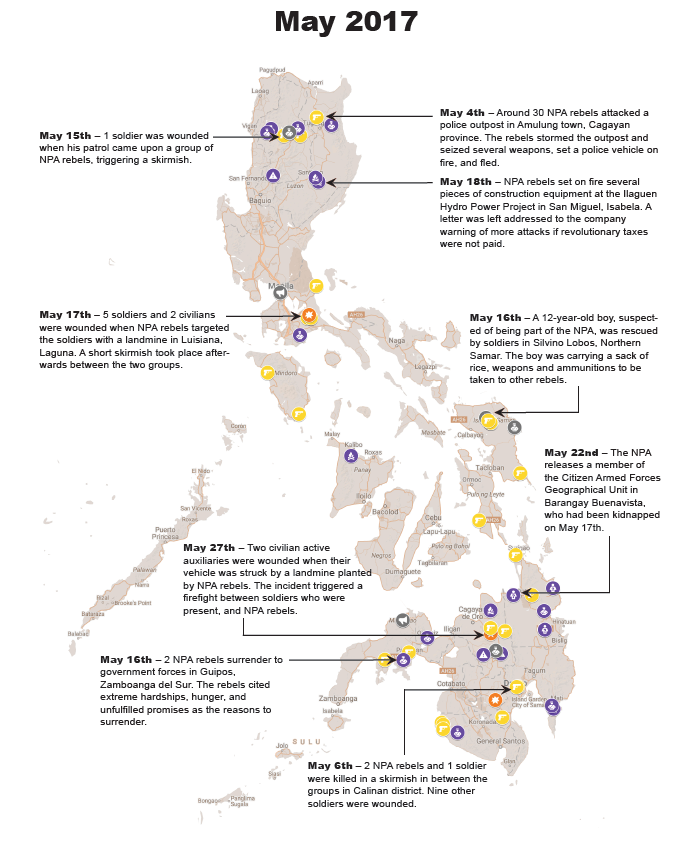

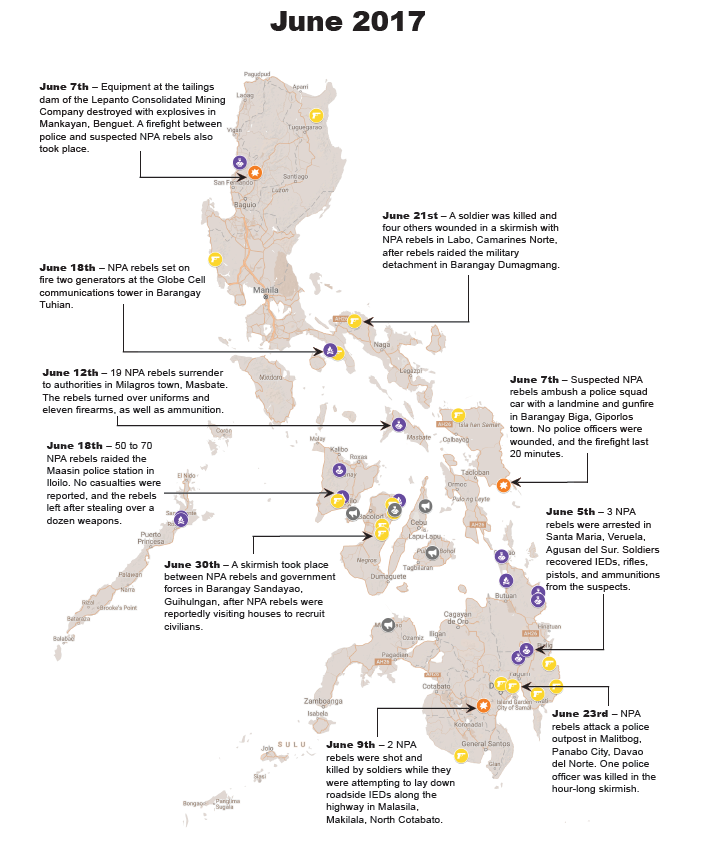

May – June 2017

After a decline in the number of incidents between February and April, the number of incidents rose again in May. However, 51 incidents out of the 62 incidents that were recorded in May took part before May 23rd, which is when the Maute Group and members of the Abu Sayyaf Group began to lay siege to Marawi City in Lanao del Sur. This shows that there was a rapid deceleration in the number of confrontations between the Army and communist rebels starting on May 23rd, as government resources began to be diverted to Marawi City to fight the Islamic militants. A day after the siege began, President Duterte declared martial law in Mindanao, a move that led communist leadership to order their own forces to carry out more attacks. This, in turn, led to the fifth round of peace talks being put on hold by the government. While the call was made for more attacks to be perpetrated by the New People’s Army in response to declaration of martial law, the NDFP which was handling back-channel negotiations with the government attempted to de-escalate the tension between the sides.

On June 7th, the NDFP asked for the NPA to redeploy to help with the fight against Islamic militants in Mindanao, despite President Duterte saying, days earlier, that he was not keen on their help. He also said that he wouldn’t negotiate with them without them implementing a unilateral ceasefire. With the offer made by the NDFP to the government, and President Duterte refusing the NPA’s help in fighting the Islamic militants, there were no recorded incidents of confrontation between communist rebels and Maute Group or Abu Sayyaf Group fighters. The first half of June continued to see a reduced number of incidents take place between the New People’s Army and government soldiers, but starting on June 18th, activity began to increase once more.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Part 3: released 24th Jan 2018.

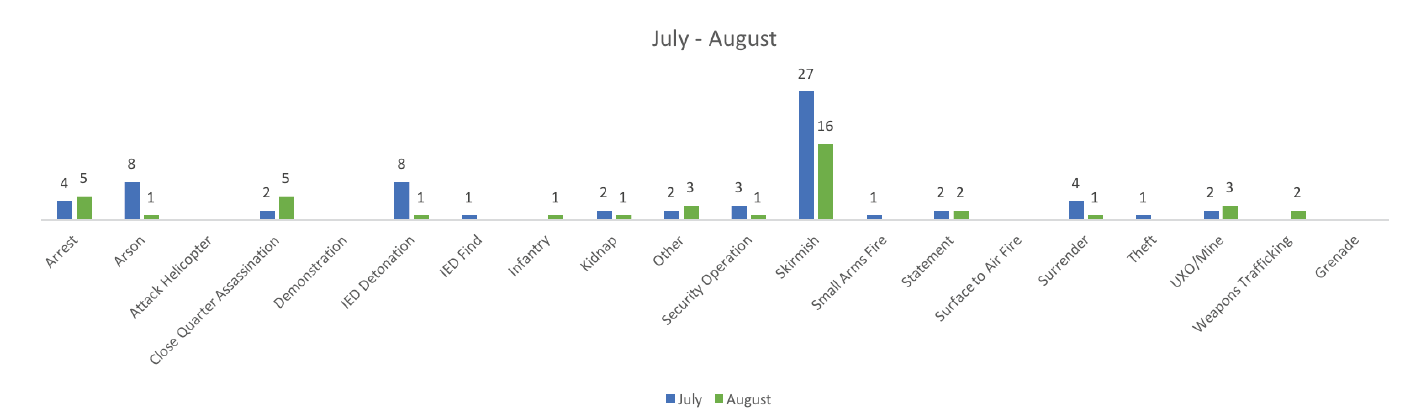

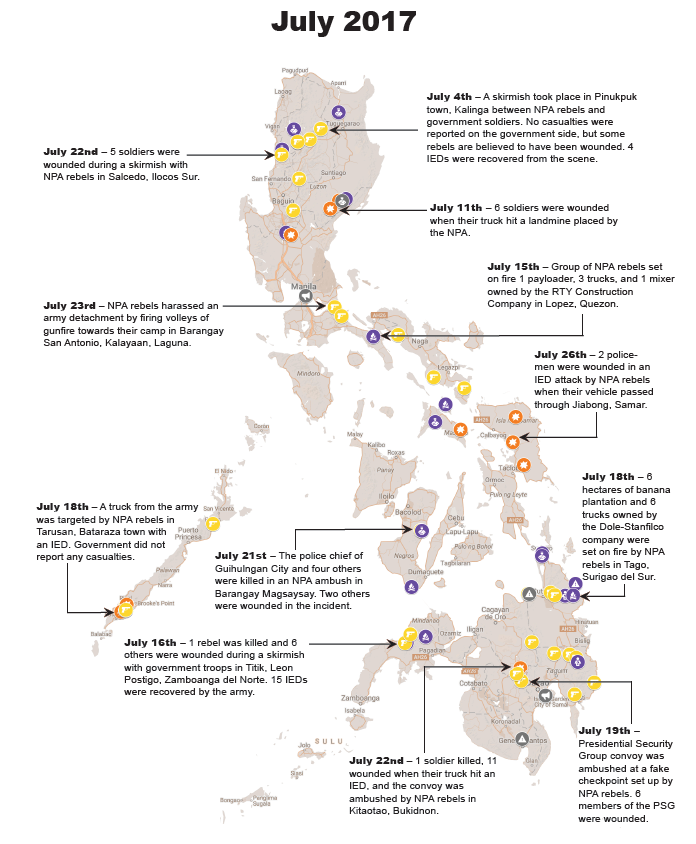

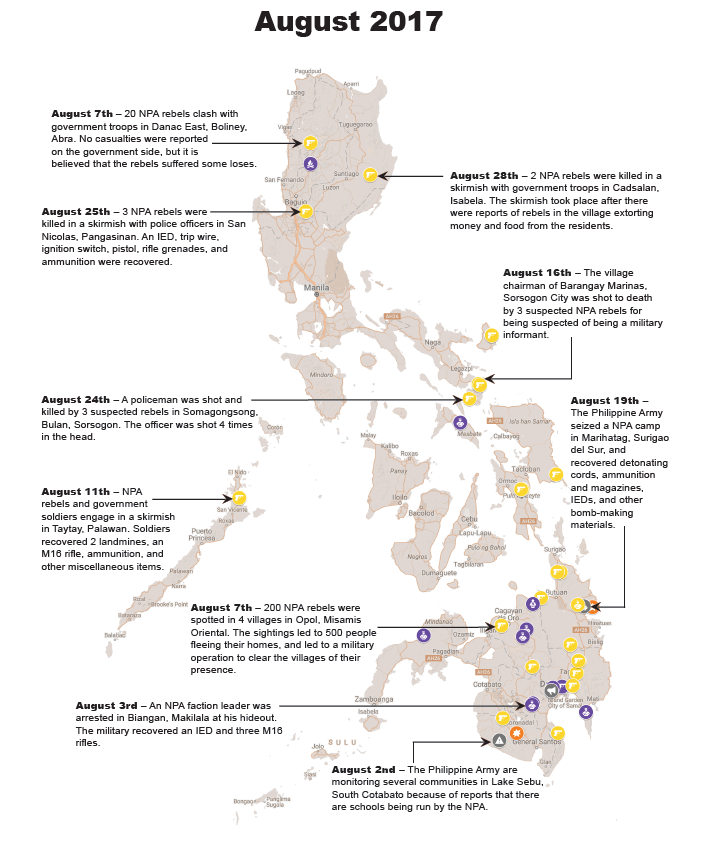

July – August 2017

The activity of the New People’s Army rose once more in July, particularly with the number of skirmishes and the use of explosives by the communist group. The 27 skirmishes recorded in July were concentrated in the regions of Luzon and Mindanao. One of these skirmishes, in Barangay Mount Diwata in Monkayo, Compostela Valley, led to the death of one soldier and the wounding of 13 others. Elsewhere, the provinces of Samar, Northern Samar, Masbate, Palawan, and Quirino saw a large number of incidents related to improvised explosive devices and landmines. Two IED detonations in Quirino province in the middle of the month saw 11 members of security forces wounded. Towards the end of July, peace talks were indefinitely suspended due to the number of attacks perpetrated by the NPA. One attack in particular, an attack on a convoy of the presidential security group, led to the government saying they would not negotiate, as well as terminating back channel talks. The attack on the convoy took place days after President Duterte asked Congress to extend martial law until the end of the year. The number of incidents recorded decreased the following month, with no significant clusters, and the majority of incidents recorded in Mindanao. The most significant skirmish in August took place in Gubat town, Sorsogon, where 2 soldiers were killed and 7 were wounded. The attack combined the use of gunfire and explosives. Finally, August saw only one Arson attack which was the lowest number of attacks since the beginning of the year.

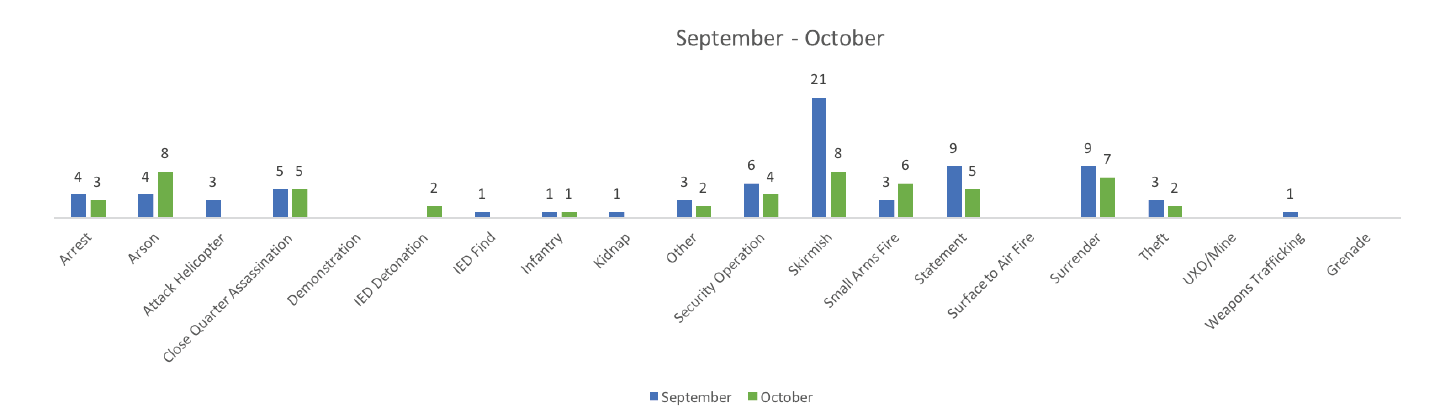

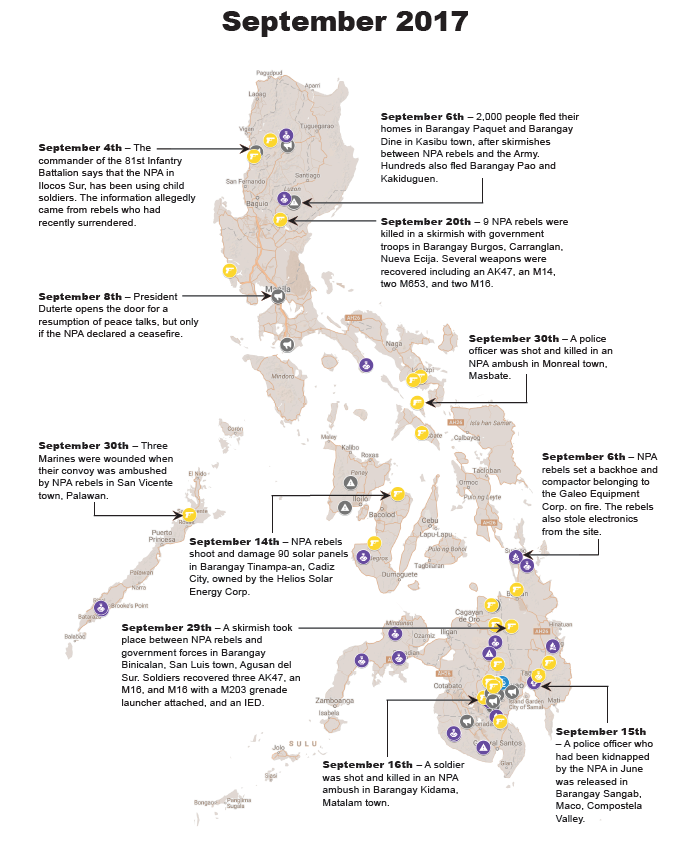

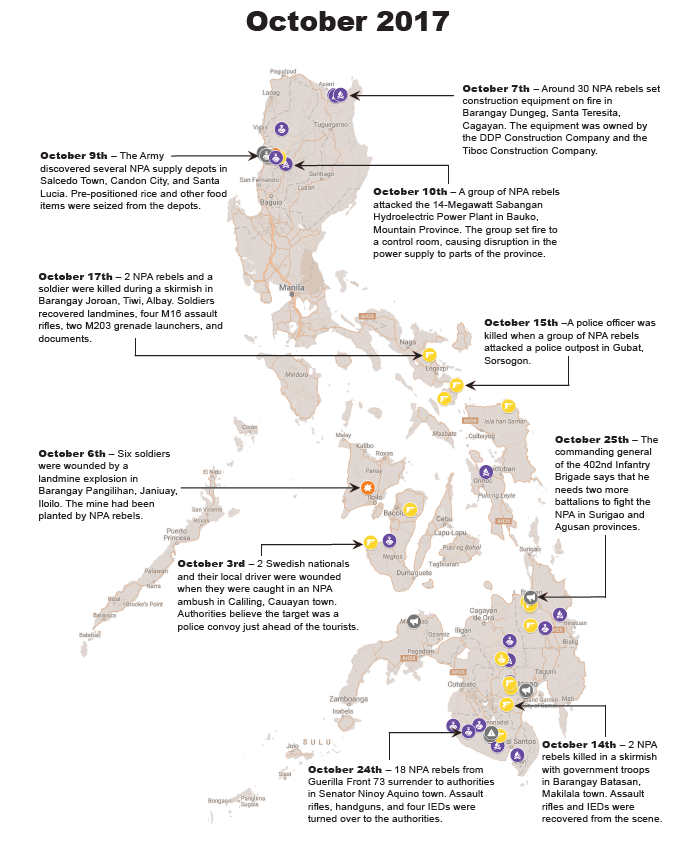

September – October 2017

Similar to what has been observed in the months prior, the number of incidents recorded rose back up in September (74) after a fall in August, and then fell again once more in October (53). Of significance was the rise in arson attacks compared to August. September saw four attacks, while October saw eight. Of these attacks 50% involved targets relating to construction companies, 33% involved equipment and products of agricultural companies, and the rest were attacks on a vehicle of unidentified use or infrastructure. A particular important arson attack took place on September 28th when communist rebels set on fire close to a dozen pieces of heavy machinery being used in the construction of the Bicol International Airport in Daraga, Albay. Police officers responded to the attack, and engaged rebels in a 30-minute firefight, but by the time they reached the airport, it was too late. Furthermore, the period of September and October saw an overall drop in both IED finds and IED detonations compared to August and September, which saw the most. Despite the overall decrease, the number of IED finds (8) remained above IED detonations (2) by a large margin. Finally, another significant decrease between the prior period and this one was the drop-in skirmishes, particularly between September (21) and October (8). The number of skirmishes recorded had never been below 10 besides for January 2017 when armed engagements between both groups had restarted. Significant incidents in this two-month period included a skirmish on September 20th, where 9 NPA rebels were killed and 1 soldier wounded in Barangay Burgos, Carranglan; a concentration of incidents around Arakan, President Roxas town, and Magpet where the army made use of attack helicopter to push back NPA activity; a concentration of incidents in Ilocos Sur where security forces discovered several supply depots of the NPA. Finally, on October 6th, a landmine explosion wounded 6 soldiers in Janiuay, Iloilo. While the two-month period ended on the decline in regard to the number of incidents, it would be the calm before the period of November and December which saw the highest number of incidents recorded this year.

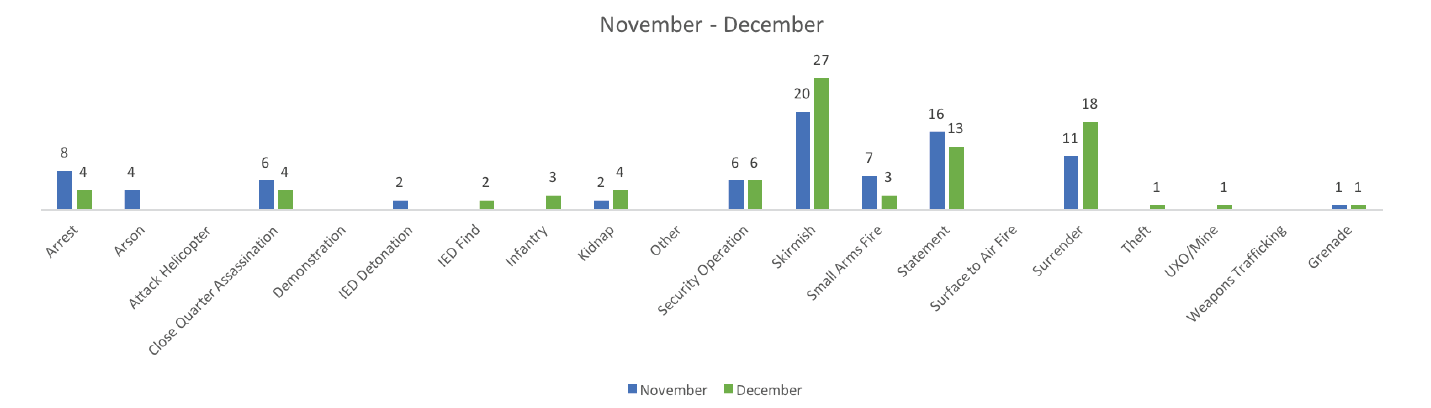

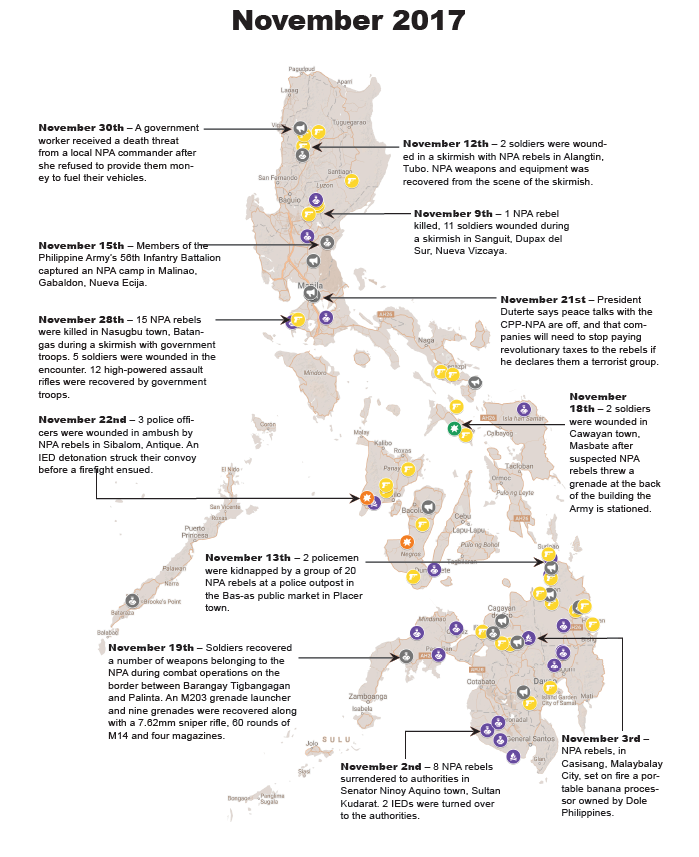

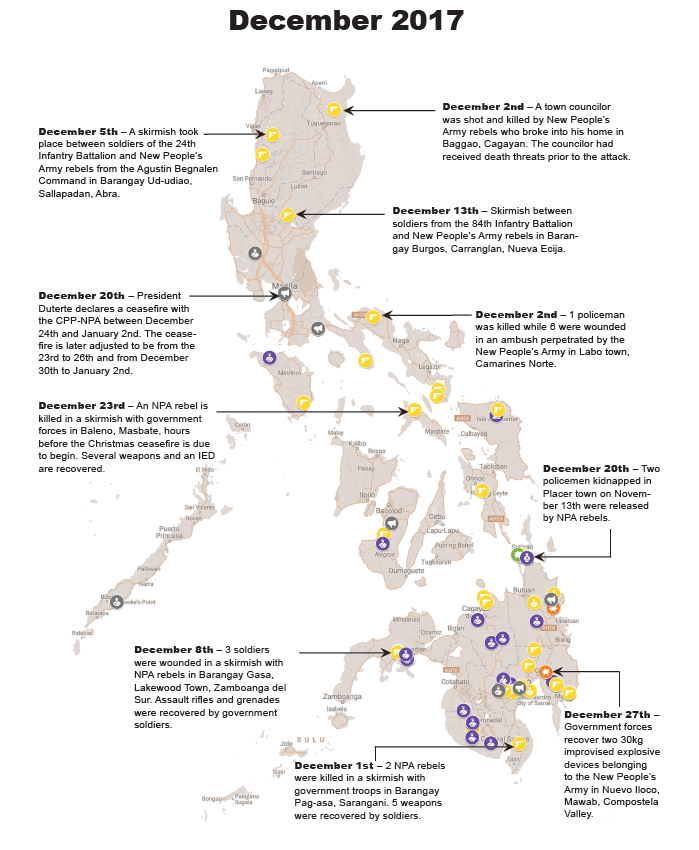

November – December 2017

November (83) and December (87) saw the largest number of incidents per month in 2017, as well as being a sharp rise in incidents from the previous month of October (53). Three important categories saw an increase from the previous months skirmished went back up to 20 and 27 for November and December respectively, but despite this, there was also an increase in the incidents of NPA rebels surrendering to authorities. Finally, Intelligence Fusion recorded an increase in the number of statements recorded. Statements include significant rhetoric from either side, and political or strategic decisions. The statements recorded in this two month period explain why the number of incidents significantly increase. Tired of NPA aggression, President Duterte put an end to peace talks with the CPP-NPA on November 21st. This move was confirmed by those in charge of the peace talks the next day. With peace talks off, the government made threats toward the CPP-NPA saying that those from the CPP, who had been released from prison to participate in the talks as consultants, may be sought and jailed once more. The rhetoric from the government side culminated with President Duterte declaring the CPP-NPA a terrorist group on December 5th. Along with this declaration was a warning that companies should cease paying extortion money to the rebels or face consequences from the government. The court case to officially classify the CPP-NPA as a terrorist group will take place in 2018.

The end of the peace talks and the labelling of the CPP-NPA as terrorists led to an increase in the groups activity against government forces as they were said to be ready to face a full-scale offensive from the government side. The majority of incidents were seen in Visayas and Mindanao, whereas the previous months had seen a more even spread in the country including in Luzon. The end of the year finished with both the government and the CPP-NPA declaring unilateral ceasefires for Christmas and for the transition to the New Year. The ceasefires took place from December 23rd to 26th and from 30th to January 2nd, 2018. Violations of the ceasefire were recorded over the Christmas period, while there was a significant armed engagement on December 28th in Davao Oriental. Several skirmishes took place on either side of a landmine exploding and damaging a military transport truck. One soldier was wounded in the skirmishes. No violations of the ceasefires were recorded between December 30th and the 2nd of January.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Part 4: released 25th Jan 2018.

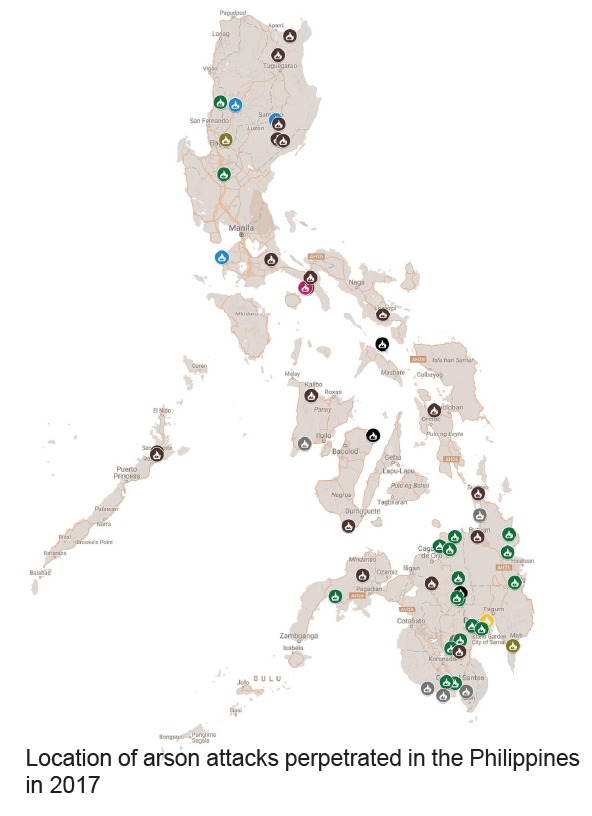

Arson Attacks.

The year saw 58 arson attacks recorded, attributed to the New People’s Army. Of these, 21 targeted construction equipment and companies, 19 impacted agricultural plantations or equipment, 7 targeted general transportation such as buses, 4 targeted abandoned military bases, 3 struck buildings of various purposes, 1 was a manufacturing plant for plastic products used in agriculture, and 1 targeted telecommunications infrastructure. The New People’s Army attacks the companies who own these vehicles, buildings, and lands in order to threaten them or in order to punish them for not paying ‘revolutionary taxes’. In regard to the attacks on agricultural targets, two of the companies most targeted were Del Monte Inc. and Dole Food Company Inc. and their subsidiaries in the Philippines. These companies are both founded and operated from the United States, and attacking them goes with the Communist Party of the Philippines and New People’s Army’s ideology of wanting to rid the Philippines of American influence. The agriculture sector makes up a large portion of the group’s arson attacks because the group sees the large companies taking over large swaths of Mindanao as being dangerous not only for small scale farmers, but also the environment. The construction sector, which makes up 36% of attacks, is attacked because the CPP-NPA does not want large scale infrastructure projects to take place which could impact the influence they might have on the rural communities from which they recruit.

The Use of Explosives.

The use of explosives has often been a part of the New People’s Army modus operandi, and in recent years the leadership of the New People’s Army has told its members to use them more often. News reports and military statements often say the attacks perpetrated by the New People’s Army, using explosives, are done so with landmines or improvised explosive devices. However, another term used by the rebels is command-detonated explosives. The use of this language is important to counteract the accusations that the rebels’ use of landmines and IEDs are in violation of international humanitarian law. Having control of the detonation of the explosive means that they are not violating the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mines Convention which bans all victim-activated anti-personnel mines. Additionally, the New People’s Army has said many times that they do not target civilians with their explosives. The use of explosives has often been used in ambushes. Rebels will detonate a roadside IED, targeting a military or police convoy, and then fire at surviving soldiers or police officers from an elevated position, usually under tree cover. This allows rebels to have the advantage in the firefight, as well as escape routes.

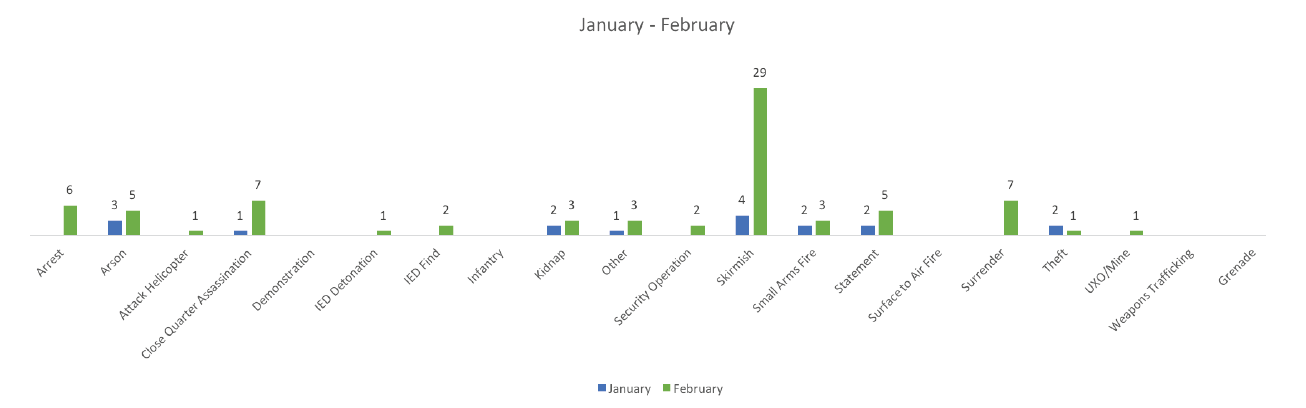

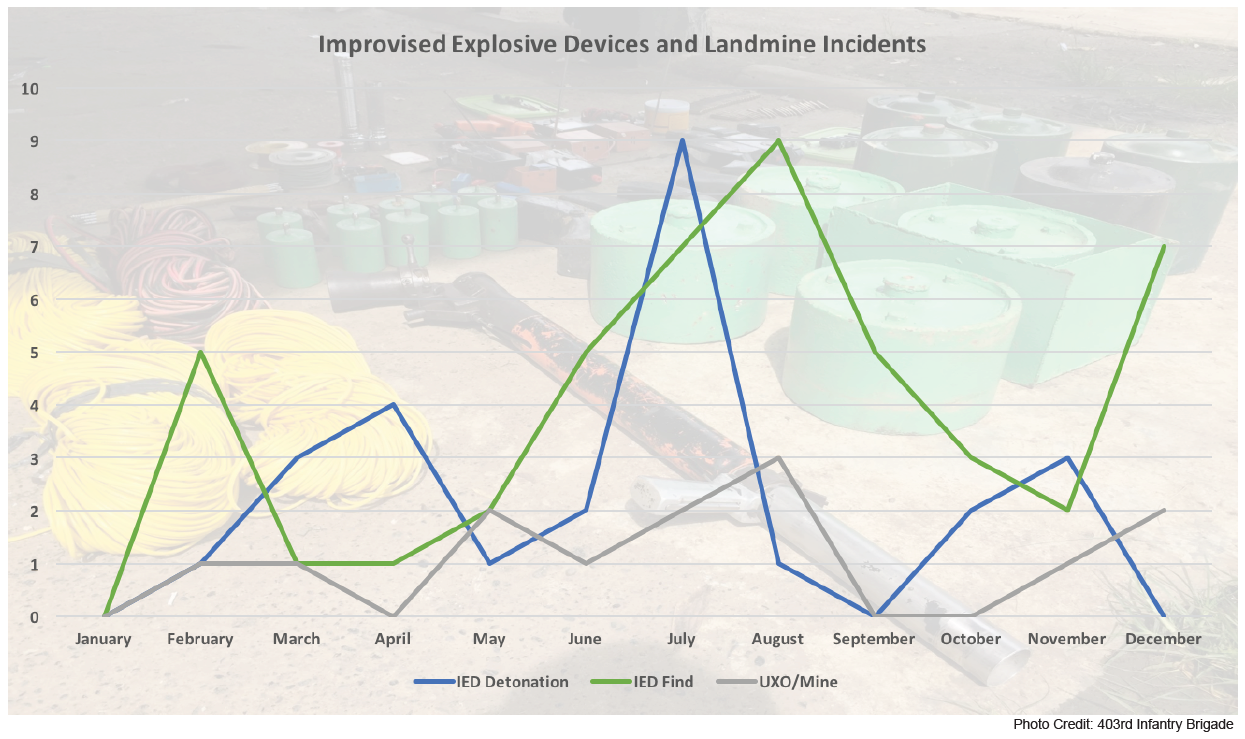

The graph above shows the number of incidents in 2017, per month, in which the NPA detonated an IED, the number of incidents where a landmine was used, and the number of incidents where IEDs or landmines were found. From April through August, the trend of IED and landmine finds by government soldiers went up, reaching a peak of 9 incidents of IED finds in August. The number of IED finds declined after August, but remained above the number of detonations recorded, that is until November when IED detonations once again surpassed IED finds, before inverting once again in December. A significant spike in IED detonations was observed in July, with many incidents taking place in Samar, Northern Samar, and Masbate provinces. Additionally, significant IED and landmine detonations were seen in July in northern Luzon, with two attacks recorded in Quirino province, wounding 6 soldiers and 5 policemen respectively. Regarding IED finds across 2017, the majority of IEDs were found when government forces were successful in overtaking NPA camps. A high number of improvised explosive devices were found in the early days of December when security forces increased their operations

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Part 5: released 26th Jan 2018.

The Year Ahead.

The New People’s Army has been engaged in an armed conflict with the Government of the Philippines for now close to 50 years. At the start of 2017, the Government and the Army were confident in having a strategy that would help defeat the group. However, the progress made to defeat the group was hampered by the activity of Islamic State aligned militants from the Maute Group and Abu Sayyaf in the form of a siege on Marawi City. The siege lasted five months, and used resources from across Mindanao that may have otherwise been used to fight the communist rebels. With the siege occurring, little attention was able to be focused on the communist rebels, but nonetheless the rhetoric from the government would be that they wanted the group to be defeated by the end of 2018. If the government’s track record on setting timelines on when they’d defeat an enemy continues, 2018 as an end date is more than likely not going to be respected. The first two weeks of January saw that target altered to instead halve the strength of the NPA, from their currently estimated 3,700 fighters. Progress, however, will be made baring any major setbacks like another Marawi-type siege by Islamic State-aligned militants in the southern region of Mindanao.

Other factors may impede any progress made against the New People’s Army. Besides worrying about a Marawi-like siege from Islamic State-aligned militants, the Armed Forces of the Philippines will have to continue regular operations against these groups which had taken place prior to May. This involves a large presence of troops in the Sulu Archipelago where the Abu Sayyaf Group has its core presence. In the beginning of 2018, it was announced that 11 battalions were back in the province to take on the militant group, and had set itself a timeline of capturing or killing senior leaders of the group by the first quarter of the year. Elsewhere, the government will have to deal with another Islamic State-aligned militant group, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters. The group ended 2017 and began 2018 with a number of attacks against government forces and civilians using improvised explosive devices and rocket propelled grenades. The activity of the group will take up time and resources for the government to defeat. Finally, there were reports after the siege of Marawi City that surviving members of the Maute Group were recruiting from the youths of Lanao del Sur in order to replenish their ranks. Government forces will need to work with local communities to ensure that the group cannot regain a foothold in the province, so as to launch new attacks against government and civilian targets. The government will also need to stop any foreign fighters from arriving in Mindanao after transiting through Malaysia and Indonesia. The siege in Marawi and the rhetoric from the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria had and continue to make the southern Philippines the ideal destination for terrorists in southeast Asia, a trend that the Army will attempt to reverse.

Besides the activity of non-state armed actors having an impact on the government’s efficiency in defeating the communist rebels, there are also factors which only the politicians and not the Army can do to help. In order to ensure future stability in Mindanao, the government must, as a priority, pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law, a final step in the implementation of the peace deal between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. The bill would create a new political entity, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region, which would replace the current Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. The past year saw little progress in its passage, but reports have said that Senators are committed to its passage, and that it will be discussed and debated in March 2018. A failure to make any significant progress in 2018, may result in youths of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front who are losing patience to splinter from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front or to join the ranks of the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters, whose origins began as a splinter group from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. Members defecting and joining such a group would make the work of the Armed Forces of the Philippines in Maguindanao much harder. Furthermore, the political goals that the Government of the Philippines may have in regard to armed groups in Mindanao may be made harder by the extension of martial law until the end of 2018.

Despite all these other armed groups in Mindanao waging some sort of conflict against the government, the New People’s Army will have to continue waging its own. The end of 2017 saw both sides of the conflict declare unilateral ceasefires, and several violations of their own ceasefire by the New People’s Army. In the period between truce periods, the New People’s Army engaged the government forces with skirmishes and landmines, particularly in Compostela Valley and Davao Oriental. In the first weeks of January, the situation has not improved, and the group’s use of explosives against the government is on the rise compared to previous months. The groups activity, while focused in Mindanao during the first couple weeks, will likely spread to the Visayas and Luzon regions. Arson attacks, after having none in December, will more than likely restart, as the group looks to finance its offensive against government forces. If the rhetoric from the past two months is any indication, the peace talks are more than likely not going to resume in the first quarter of 2018. Political pressure from politicians at the national and local level may lead to attempts at discussion, but any form of ceasefire or peace deal also depends on the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army. The group has seen a large number of defections in the last year, and a drop in their numbers could put pressure on them to seek a solution other than a full-out offensive from the government. Additionally, the CPP’s Second Party Congress in 2016, which was focused on increasing the number of youth and middle-aged individuals in cadre positions may have an effect on the route the CPP and the NPA takes, but 2017 did not show a differing perspective to previous years. Only time will tell which route both parties will take, but the near future only promises continued violence.