The Economics of Libya

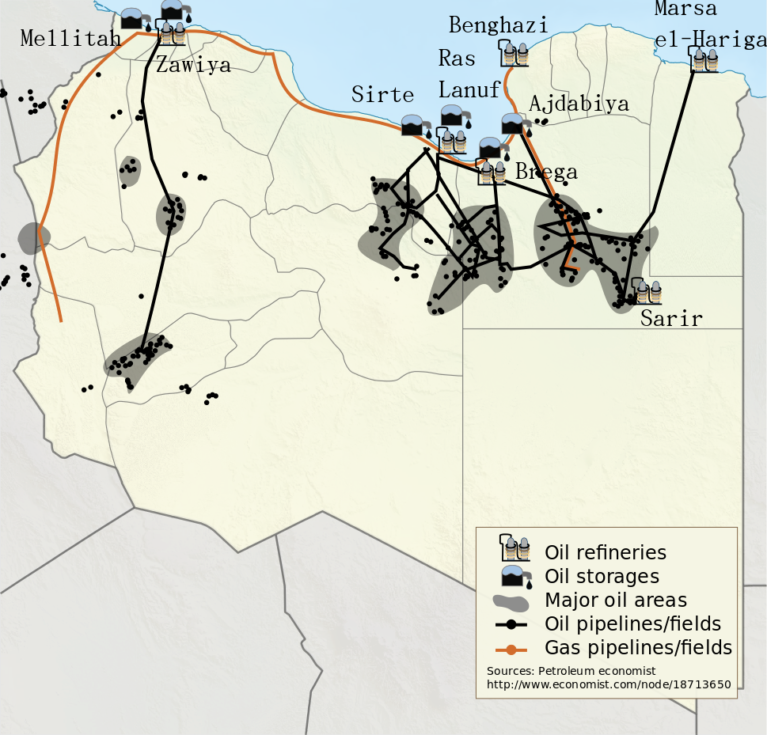

Oil has been the driver of the Libyan economy ever since its discovery in the 1950s and since it obtained exporter status, 1961. At the height of its economic power, pre-Libyan Revolution, oil exports accounted for 95 percent of export earnings and 60 percent of GDP (including gas), according to OPEC. Other exports can be seen here.

âIn 2010, before the Arab Spring and the popular uprising in Libya, the EU was an important trading partner for Libya accounting for 70% of the countryâs total trade, which amounted to approximately â¬36.3 billion in 2010. However, between 2012 and 2014 EU imports from Libya decreased by 38%.â

Libyan exports have since dropped, falling at an annual rate of -12.5%.

Libya averaged about 1.7 million BPD. Oil output dropped considerably to 300,000 bpd in October 2015. At present, oil output lies at less than 400,000 bpd. The latest standoff between eastern and western governments threatens to drop this figure to around 120, 000 bpd. The fall in global oil prices have had an almost catastrophic effect on those economies that are highly dependent on oil exports. Granted there are varied dynamics that influence oil prices, demand, oversupply, energy alternatives and technological change look to be key drivers of oil change in the coming years, if not the short-term then the long-term. For now, however, oil prices look set for a gradual increase over the coming years, and a shift in demand towards Asia means oil will remain a valuable commodity.

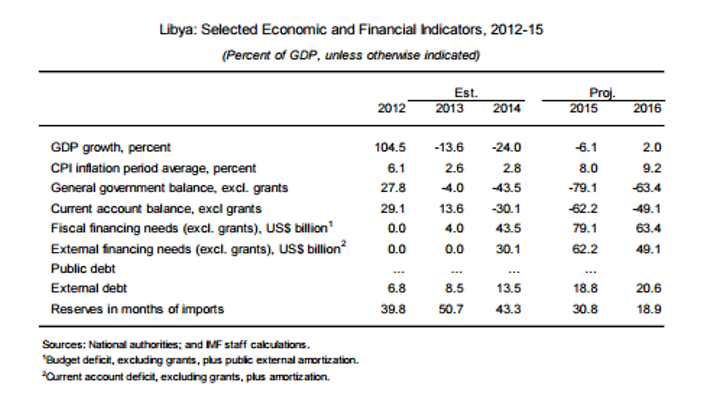

Further instability in Libya will continue to push Libya towards economic debt and collapse as the risk of bankruptcy increases. Diversification of trade exports would certainly strengthen Libyaâs economic resilience.

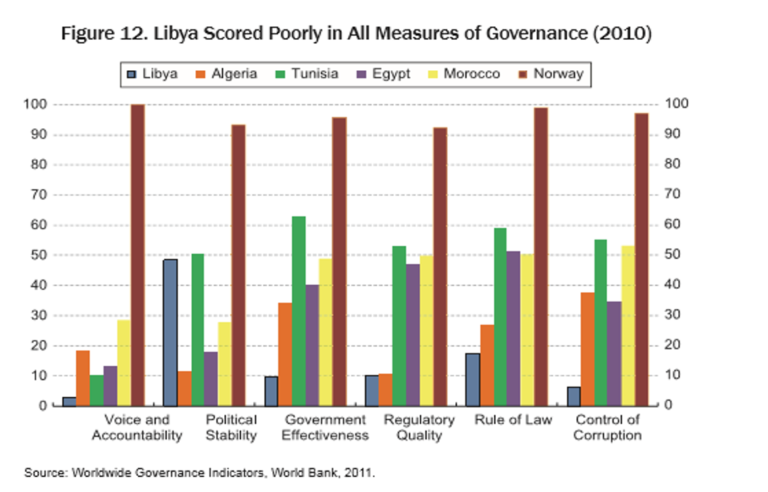

The Libyan economic structure during the Gaddafi reign was one based on the economic ideology set forth in the second volume of his âGreen Bookâ. Consequently, the economy, in all vital sectors, was run according to untested, inefficient principles. Reforms, produced a system rife with corruption and mismanagement, and devastated the traditional merchant class. The highly centralised, socialist economy never developed a middle class. No privately-owned companies were established that were capable of operating in the oil or even non-oil related fields. The public sector accounted for approximately 70 percent of economic activity. Policies of liberalisation were instituted in the 90s and in 2008 the country opened its stock market. Some argue that policies of liberalisation, that continued throughout the 00s, were heavily inclined towards the oil and gas industry. Nevertheless, liberalisation initiatives continue to this day and it is fundamentally important that they do if the country is going to transition to a market-based economy. Moreover, public sector reforms must also be accompanied by decentralisation of the state for reasons of local empowerment and transparency, and streamlining of the public sector to improve state efficiency (the upskilling of the Libyan economy is also a necessity for future investment in the country). A host of challenges facing Libya is enumerated by the IMF in their comprehensive report.

Economic/fiscal reforms must run in parallel with political and governance reform. The road to a market-based, resilient economy is a long and complex one. In the short-term, however, Libya and the GNA must resolve the liquidity crisis and satiate short-term needs of the population. This is by no means an easy task as various actors jostle for power, but time is running out on the economic front given the magnitude of structural changes that must be made in the country.