The Complexity of Libyan Unity

The recent Libyan political process has by no means been a smooth one. Critics have pointed to its weak legal basis and say the agreement does not fairly represent Libyans, within the three Libyan regions (Tarabulus, Barqah and Fezzan). Nouri Abu Sahmain, Dar al-Ifta (headquarters of Grand Mufti Sadiq Al Ghariyani) and Salafist groups (such as BRSC, DMSC and perhaps local, lesser known Salafist groups), except for the Justice and Construction party (Libyan Muslim Brotherhood), oppose the agreement. Barqah is less developed than western Libya despite the countryâs wealth originating from the region and tribes and people have long called for greater autonomy. It remains to be seen if the GNA can meet federalist demands led by Cyrenaica Defence Forces and Ibrahim Jadhran.

There was reluctance in the GNC, with its Prime Minister Khalifa Ghweil backtracking on earlier comments about ceding power to Prime Minister designate Serraj. Nevertheless, the GNC released a statement declaring it was âceasing the activities entrusted to us as an executive powerâ in order to âpreserve the higher interests of the country and prevent bloodshed and divisionsâ. They also announced the creation of the State Council. Yet, reports have emerged claiming the GNC has not completely dissolved and that they do still congregate (Abdulrahman Sewehli, president of the State Council, took control of Rixos Hotel complex formerly the location where the GNC used to convene) at an unknown location, possibly with Nouri Abu Sahmain (president of the GNC) at helm. As exemplified in a GNC statement released on April 12th 2016: âThe GNC calls for reformation of the Presidency Council which entered Tripoli and is trying to impose itself by force, thus it became a party in the conflict. The GNC rejects the formation of the so-called High State Council by its members. It confirms that this council should represent all constituencies and political parties who took part in the GNC elections. The GNC also asked the Salvation Government to continue working according to the constitutional declaration, considering it as the only legitimate government in Libya.â

House of Representatives (HoR)

The HoR on the other hand, have received persistent support from the UAE and Egypt. Within the HoR there is a significant pro-GNA faction, however in order to vote on the unity agreement, HoR president Aguila Saleh needs to convene the house for a vote to take place. However, bylaws and pressure may force a vote and signs are positive. On Thursday 21 April, 102 MPs expressed confidence in the GNA. One can infer that if there is support for the GNA, then a preceding vote on a constitutional amendment will also be passed by the HoR. Another dominant faction is one that supports General Haftar. Those that oppose the unity agreement denounce it on grounds that it is a product of western interests. Opponents in the GNC and HoR earlier this year called for a separate track of negotiations often referred to as Libyan-Libyan dialogue. Therefore, any question of a foreign intervention is a sensitive issue.

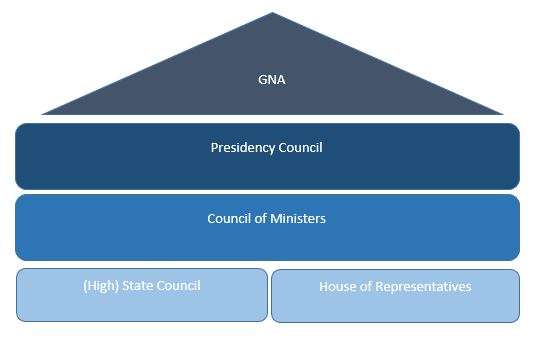

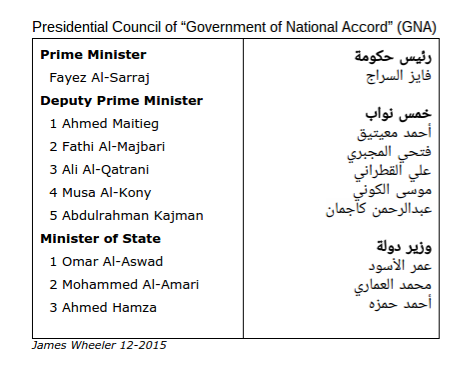

GNA

The state council had their first meeting on Friday 22nd April. On 31st March 2016, the GNA also received the backing of ten municipalities (Sabratha, Surman, Ajaylat, Zawiyah, North Zawiyah, South Zawiyah, Zuwara, Zelten, Riqdalin and Jumayl). Furthermore, the GNC had become increasingly isolated internationally, and they couldnât muster enough local support to justify military action towards the GNA. This is partly because the Libyan population taken as a whole are growing in frustration with the impact political division is having on everyday life. The GNA has also received the backing of key institutions, the Libyan Central Bank and the National Oil Corporation and key ministries. On 7th April 2016, the GNA took administrative control of seven ministries (housing and public utilities, transport, social affairs, local government, youth and sports, and Islamic affairs) in Tripoli including the foreign ministry. The planning, labour, and education ministries will soon be under GNA control. What is fundamentally important is that a strategy is drawn to immediately address other urgent problems in Libya (economic, unpaid salaries, humanitarian aid, infrastructure, medical situation) if the GNA are to win support among the population.

Militias

Given that there was no major conflict in Tripoli in the aftermath of the GNAâs arrival, we can assume that the GNA has the backing of strong militias in Tripoli, perhaps from most militias in the country. Conversely, according to the BBC, there is a split within the Misratan militias over support for the GNA. The Tripoli home of Ahmed Maetig, member of the presidency council, was attacked possibly by Haitem Tajouriâs Tripoli Revolutionariesâ Brigade. Juma Sayehâs Tripoli home was also attacked after he had announced his support for a rival State Council. The extent of the challenge the GNA faces in appeasing militias is extremely complex. Every militia have their own interest and conditions they want met. The complexity is perfectly summed up by recent reports of roads in Tripoli being blocked, electricity shut down in Tripoli by a militia in Khoms, other militias can turn off the water supply to the capital or natural gas pipeline to Italy, as has occurred, should they choose to.

General Haftar

Perhaps the biggest sticking point for Misrataâs militias and former Libya Dawn members, is General Khalifa Haftar, leader of the Libyan National Army (LNA). The LNA provide the muscle to the House of Representatives. Having gained massive support in Benghazi since the start of the Blood of the Martyrâs operation earlier this year, the LNA and General Haftar hold a lot of political leverage in Benghazi, though his popularity among tribes in eastern states of Al Bayda and Tobruk is by no means solid. General Haftar, former dissident and member of the armed forces under the Gaddafi regime, lived in exile in America until the revolution and is thought to have links to the CIA, is wary of his position or influence as part of the GNA. If General Haftar was to take up a role in the GNA, he would operate under Minister of Defence, Mahdi al-Barghathi. An obstacle going ahead, one that has been highlighted during the drafting of the Libyan Political agreement, is the fate of General Haftar. Article 8 of the political agreement states that all military positions should immediately become vacant after signing of the agreement. Given that Haftar is a former military officer under the Gaddafi regime and part of the Anti-Islamist bloc, it would be better if the Libyan Armed Forces appointed a neutral candidate. Such an appointment, without compromise from General Haftar, is far-fetched given the enormous influence he holds in the HoR. Haftarâs credentials have been questioned by Mohamed Al-Hejazi, ex-high ranking LNA officer who accuses Haftar of stealing, killing and torture. Nonetheless, according to prominent Libyan analyst Mohammed Eljahr, a compromise could be reached to drop or freeze Article 8 altogether. Moreover, Misratan militias showed their pragmatism when they released Mohammed Bin Nayel one of the most despised pro-Gaddafi generals in a prisoner swap with the LNA in Fezzan Still, Haftar has supporters within the GNAâs presidency council, from figures such as Ali al-Qatrani.

Recent troop movements indicate that a Sirte offensive will likely be launched by the LNA and Misratan militias, it is unlikely LNA and Misrata will coordinate, what is clear is the GNA oppose any such action by either side. It seems that both are trying to strengthen their bargaining position and their popularity in the eyes of many Libyans.

International Support

Internationally, the western powers have put their political weight behind the unity government as have Algeria. A former Algerian intelligence network may still be effective and Algeria maintain good links with Tuareg families on both sides of the border. They are well placed to intervene in times of conflict in the south of Libya, and they have sizeable military resources on the Libyan border (30,000 to 40,000 Algerian soldiers). The GNA were previously based in Tunis before making the move to Tripoli, in and of itself a show of support, and Tunisia will likely support any government that ensures stability taking into account the fact that Libyan trained IS fighters have contributed to a downturn of Tunisiaâs economy. The Egyptian Foreign Minister, Sameh Shoukry, pushed the HoR to endorse the GNA but have made clear they do not want Western military intervention. They also remain fervent supporters of Haftar along with the UAE. The Sisi regime are probably keen to avoid an Islamist government on their western border, given the post-revolution events in Egypt and the impact an Islamist Libya might have inside Egypt. Chad and Niger maintain good relations with the U.S. and France. Along with Sudan, all bordering nations have shown support for the UN-led process.

Along with Sudan, all three lack good governance and border security for a number of reasons. Undeniably, poor governance (depending on how it is defined) and porous borders are features attributed to many if not all states in Africa and while programs can be put in place to mend such weaknesses, they must do so in parallel with initiatives to combat socio-economic woes in the region. Such a holistic strategy is ambitious yet warranted due to cross border communal linkages (mainly among the Tuareg and Tebu peoples) along Libyaâs southern border nations. Officials in the intelligence community have warned that IS fighters are moving to the Fezzan region to avoid airstrikes (U.S. reconnaissance drones are expected to hover over Libyan skies soon). There have been reports of Boko Haram smuggling fighters to Libya, and weapons flow to Boko Haram through Chad.