South East Asia’s Amphetamine Crisis

Overview

Second only to opioids such as heroin, amphetamines have become the most prevalent drug group in counter-narcotics operations across the world. In South East Asia in particular, methamphetamine addiction has become the most severe regional narcotics issue, having surpassed even the North American trade for the first time in 2015.

The Greater Mekong Subregion, which spans parts of Southern China, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar, is especially significant. There, police seizures of crystalline or tablet amphetamines have multiplied fivefold since 2006, whereas heroin seizures have increased comparatively slowly, by 75% in the same period. At the borders of nearby high-income markets such as Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea, shipment interceptions are dramatically increasing, and further exports to the Philippines have fuelled new Pacific intelligence partnerships.

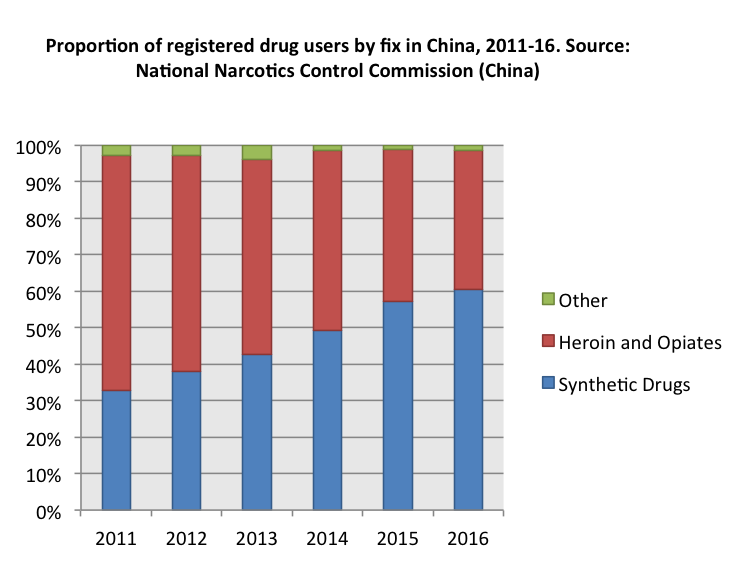

As the largest stakeholder in the region, China features heavily at all three levels of the trade: production, transit, and consumption. Chinese organised criminal networks, particularly the Triads operating mostly out of Guangdong Province and Taiwan, are the initiators of a lucrative production process that ends with over a million consumers. Over 80% of Chinaâs 450,000 newly registered drug users in 2015 primarily consumed methamphetamine. They now constitute over 60% of all users nationwide.

The declining retail price of methamphetamine, in spite of its stable purity, indicates a surge in production that has been reflected in consumer-level pathologies such as addiction and disease, as well as police crackdowns. This transnational illicit industry can shed light on the public health, crime, and security dynamics of a growing regional crisis.

Production, Transit & Consumption

Unlike for heroin, cocaine, and cannabis, the production of methamphetamine has no environmental requirements beyond a laboratory. No form of agriculture is needed, and as long as the skills and precursor chemicals can be acquired, money can be made on sites that are invisible to common counter-narcotics techniques such as crop surveys. Clandestine laboratories have been raided in apartment blocks, on pig farms, and onboard ships in the South China Sea.

The largest labs can produce a daily output of 200kg of methamphetamine, each kilogram having a street value of $120,000. Low-level producers can earn Â¥10,000 per day at this rate, which is equivalent to the monthly intake of many white-collar jobs. Professional âcooksâ can make twice that.

Since at least 2015, Guangdong Province in mainland China has been the epicentre of production, and its exports play a major role in the regional âiceâ crisis. The province has an abundance of international transport links, and a large legitimate chemicals industry that makes the diversion of precursors such as ephedrine, P-2-P, and benzaldehyde difficult to trace. Zhaoqing and Shanwei are both major hubs, with the latter accounting for half of the domestic consumption of Chinese methamphetamine.

Outside of Guangdong, the mountainous border area between Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand known as the âGolden Triangleâ is of central concern. There, producers benefit from a high addiction rate, a well-established narcotics network that has operated since the 1950s, and the backing of local paramilitary groups.

From these two regions, methamphetamine is exported throughout South East Asia and outwards to Australia, Europe, and North America. According to the Drug Abuse Information Network for Asia and the Pacific (DAINAP), almost all samples seized by police that are traceable to Guangdong have a purity of over 90%, while the Golden Triangle average is over 80%.

Once cooked, methamphetamine is distributed to dozens of destinations across the region. Individual online sales are increasingly prevalent, but most wholesale shipments are transported to Australasia and the Philippines, or beyond to the U.S., Mexico, and Western Europe. Cargo can be hidden among legitimate goods, or absorbed into onboard materials in order to be secreted later.

“If you want to smuggle a product into a country, whatever the illicit commodity is, you have to have a large trade stream to hide it. If you only have 100 packages coming in then you only have 100 packages to hide your stuff. Now, if you have 100,000 packages âand the same amount of drugs â the chances of getting caught are much less.”

– John Coyne, Head of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute

The gambling trade in South East Asian metropolises such as Manila and Macau provides a straightforward laundering mechanism for amphetamine traffickers. Narcotics sales are frequently conducted with wealthy individuals at casinos, after which the money is exchanged for chips and distributed largely without risk. Regulation of the casino and banking industries is often lax, particularly in the Philippines, where such institutions have effectively been made exempt from anti-laundering monitoring in an attempt to increase business.

When it comes to amphetamine consumption, it is Australian drug users who pay the highest retail price per user; typically, 1g of crystalline methamphetamine there costs $58 (a 33% decrease since 2013). As is invariably the case across the world, the majority of regular consumers are the most vulnerable in society, such as sex workers or street children. They suffer the brunt of the public health consequences of amphetamine proliferation, including rapid dental decay, sexually transmitted infections, and psychiatric disorders. The nations of the Greater Mekong Subregion faced spikes in health and social care spending during the last amphetamine epidemic between 1997 and 2001, and are undergoing similar surges in requests for treatment.

Regional Counter-Narcotics

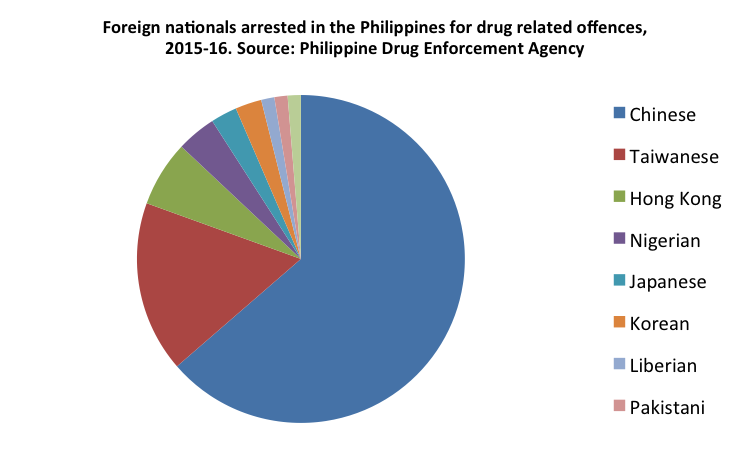

Three of the most prominent actors in the counter-narcotics of South East Asia are China, the Philippines, and Australia. Commissioner of the Australian Border Force Roman Quaedvlieg has warned against a further rise of airborne amphetamine trafficking from China and Hong Kong, and each of the three powers has expressed mounting concern over the production and consumption of methamphetamine. It is the Sino-Filipino partnership that is leading the way in intelligence-led suppression, however.

China has vowed to step up âreal-time information exchange, close case coordination, [and] timely joint combat operationsâ to fight trafficking. In practical terms, thousands of arrests have been made and hundreds of laboratories dismantled. In 2016, for instance, 168,000 suspected traffickers were detained. However, many of the Chinese cooks are Triads, so counter-narcotics is necessarily linked with broader police efforts against organised crime that are similarly hindered by official corruption.

In addition, Beijing offered to provide the Philippines anti-drug training, test equipment and technical support – a promise equalled by the American DEA in Manila in spite of frosty diplomatic relations. China may seek to continue appeasing Duterte, as he has led a political pivot away from the West, but the partnership fluctuates regularly. Alleged high-profile corruption is also an issue in Filipino counter-narcotics. Davao Vice Mayor Paolo Duterte, the son of the President, has been linked to trafficking activities, but denies the allegations.

A senior Filipino justice official has described the country’s current and past efforts as “whack-a-mole”, which encapsulates the chronic inadequacy of hard-power-based responses the world over. While tackling the producers and criminalising the consumers is often a populist move with short-term superficial results, it may only be the long-term, softer approaches that undermine the industry. Drug education and the regulation of licit chemical industries appear to be reasonable steps, and the international cooperation shown by China and the Philippines, and by the three Mekong States, is an encouraging development.

Sources:

UNODC

DAINAP

The Drug & Alcohol Review Journal

Chinese National Narcotics Control Commission

Reuters

GMA Network

China Daily

PRI Global Post