Recap: Libya 2017

Political developments in 2017

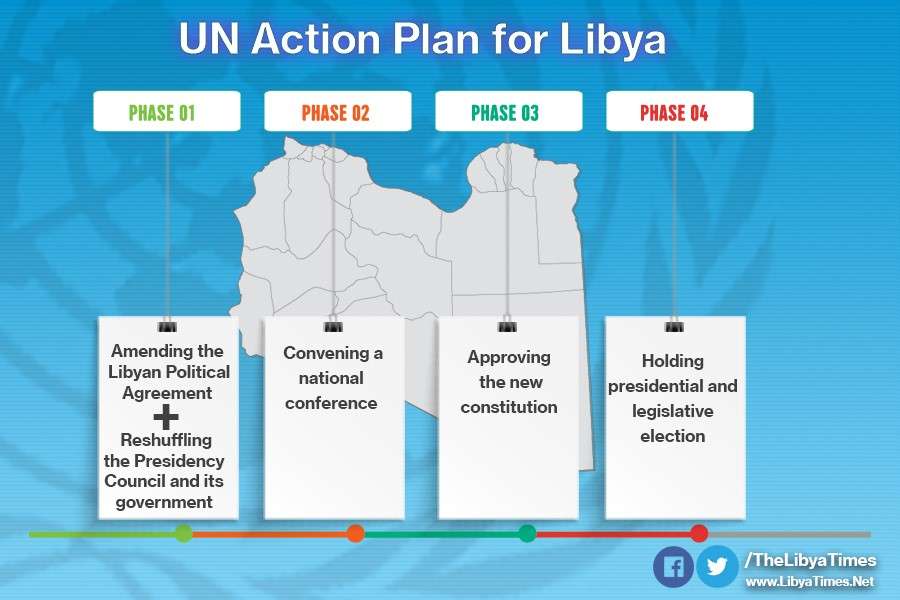

UN Action Plan

The HoR are yet to vote to include the LPA in the constitutional declaration. Quorum was not reached on two recent attempts to vote. That too without consensus, Serraj also recentlycalled on the international community to push factions hindering the implementation of the Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) to commit to it. Prior to Serraj’s call, Haftar, in a televised speech, declared the LPA’s mandate, and bodies formed by it, would expire on December 17th 2017. Under the 2015 accord it was renewable only once – UNSMIL denied that it had expired.

The Libyan economy

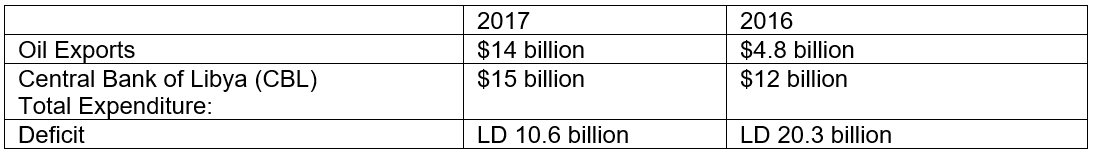

Total spending and the budget deficit was down from 2016 and there was no deficit on balance of payments. However, spending on development projects was down and state sector salaries still take up 62 percent of spending. Together with operational spending and subsidies they take up 96 percent of total state spending.

The uptick in oil exports is encouraging. However, the lack of liquidity in banks prevents Libyans from accessing their salaries, the dinar’s value has deteriorated and use of black market currency exchange is entrenched. The causes and propagating factors behind the monetary crisis are, broadly speaking: structural, political, security and even social/cultural. Despite this,the CBL governor, Sadiq al Kabir, painted a positive picture in early 2017, stating the amount of liquidity circulating outside the banking industry had increased to approximately LD 30 billion, up to 70 percent of the total compared to 9 percent in 2010. The civil war, he said, has eroded confidence in the banking sector and left many businesses incapable of operating. Kabir said the healing of political divisions, uniting of key institutions (the Al Bayda HoR government has set up parallel institutions), curbing of public spending, reviving the private sector and boosting growth and investment opportunities is necessary to solve the country’s economic problems. The CBL has come in for criticism from the NOC, Audit Bureau and PC for its policy, or lack thereof, related to the connected issues that are the black market currency exchange, the liquidity crisis and currency devaluation. Kabir has since been replaced by Mohammed Shukri, a banker with credible experience, appointed by the HoR in contentious circumstances but is now accepted by UNSMIL and the HCS. Shukri is yet to take up the role as CBL governor.

The Audit Bureau, the state body responsible for monitoring financial performance of state institutions, was damning of the lack of oversight by the HoR of institutions playing a major role in the country’s financial affairs. This, as is argued in the 2016 report (released in the first quarter of 2017), is borne out of the HoR’s failure to vote in favour of the LPA and GNA. This failure led to numerous financial entities (the Ministry of Finance, Planning, the Central Bank of Libya) operating in isolation, without coordination thus leading to overlap, confusion and poor performance. Lack of harmony between the legislature and executive led to weak performance of state authorities.

The report also stated corruption is practiced by 86 percent of Libyan society and corruption specifically in the banking sector is a threat to the economy. In the banking sector, corruption is practised in at least nine ways: money smuggling through LCs and banking transfers, false or undervalued imports, banks accepting money laundering transactions through LC manipulation, manipulation in the use of debit cards, fake deposits through the manipulation of the clearing system, manipulation and misuse of guaranteed cheques, over-extending credit and loans, extending loans and cover without collateral, accepting bad cheques and debiting them from state accounts. The CBL has, since the revolution, been criticised for not doing enough to combat corruption. However, it argues that it is not its job to police financial crime.

Tripoli

The security situation has improved slightly in 2017 in that there were fewer, intense skirmishes between pro-GNC and pro-GNA militias/armed groups. While armed groups carry out roles that would otherwise be fulfilled by police, they have also been involved in a number of illicit activities and operate with no transparency or accountability. Throughout Libya, armed groups, while not all are directly involved in criminal activities such as weapons, narcotics or people smuggling, many will facilitate their movement through checkpoints and territory they control. An EU internal report described intra-ministry divisions, a lack of coordination as well as broader divisions/challenges in Libya is inhibiting the execution of an EU-backed security plan in Tripoli and complicating EU security personnel from supporting capacity-building efforts. The EUbam mission is also working with the GNA ministry to establish a link to Interpol’s global police communications system and Europol have sent an expert to support the Libyan police in the fight against trafficking and smuggling of human beings. Interpol may also send facial identification systems to improve Libya’s counter-terrorism efforts.

The major pro-GNA forces in Tripoli at present are:

RADA Special Deterrent Force – a group which adheres to the Madkhali Salafi strain and led by Abdul Rauf Kara. They are now in control of Mitiga airport, after they expelled the Buni militia (a GNC-affiliated militia that previously secured the airport). They are suspected of being behind attacks on Sufi Shrines in Tripoli and extra-judicial killings of Islamists. They frequently carry out raids on alcohol manufacturing facilities, arrest drug dealers and criminal gangs in mainly northern Tripoli, but have recently cooperated with forces in the Aziziyah area of Tripoli during the GNA Western Military Zone’s operation to ‘cleanse the area of criminals’. They also execute counter-terrorism operations in Tripoli. Madkhali Salafists are fervently opposed to all forms of political Islam. In Mitiga, they operate a prison where, according to the UN, 300 to 500 individuals with alleged affiliations with ‘terror organisations’ are being held.

Tripoli Revolutionaries Brigade – The largest militia in Tripoli, also known as the First Security Division of the Central General Security Administration, it is led by its commander, Haithem Tajouri. They operate out of their HQ in the Shara al Shatt area near the Mahary Radisson Blu hotel, and the Mazara‘at al-Na‘am camp in Tajoura, a private detention centre where after the revolution the brigade detained numerous regime officials. The UN Panel of Experts report in 2017 detailed Haithem Tajouri’s involvement in LC (Letters of Credit) fraud and corruption; kidnap, detention and torture of journalists and activists; and the extortion of large sums of money from visitors to the Mazara‘at al-Na‘am camp and of Central Bank employees. One case shows extortionists connected to TRB and its associates were granted LCs worth $20 million. Tajouri has been described as less a political figure but an individual seeking to protect interests he has amassed since the revolution.

301 Battalion – A powerful Misratan militia now part of the GNA MoD, the battalion mainly operates in south-western areas of Tripoli such as Sawani, Al Krama and Al Hadba with HQ on Airport Road in Tripoli. Together with the 303 and 302 Battalion, they form the Halbous Brigade which has a large presence in Misrata. Its commander, Mohammed Al-Haddad, was appointed the chief of the Central Military Zone (that is supposed to stretch from Tripoli to Zuetina – in reality, Misratan presence does not extend further east than Sirte).

Abu Salim Central Security Force (Ghenaiwa militia) – Led by Abdulgani Kikli, operates mainly in the Abu Salim area where he controls a detention facility. Several individuals held at the facility, which has a torture room, ended up with severe injuries. They recently cooperated with the 301 Battalion and an anti-terror unit to diffuse a VBIED in the Edraiby area of Tripoli.

Nawasi Brigade (also known as Central Security Force or Eighth Force – not to be confused with Central Security Forces that are part of the interior ministries in eastern and western Libya) – The brigade was previously part of, or linked to the RADA SDF. Though in recent battles in Tripoli, it has fought alongside the TRB and RADA SDF. The Brigade is vehemently opposed to Haftar. They have clashed with the Ghazewy Brigade in the Old City area of Tripoli and the TRB. Interestingly, clashes with the Ghazewy Brigade, who had a heavy presence in the Old City area, may have been related to rival black market currency dealers, which both sides protect.

Presidential Guard – The Presidential Guard was set up as a transitional force to be integrated into a future Libyan army once consensus is reached on a command structure. The PG is led by Najmi Al-Nakowa. It is securing a stretch of the coastal road between Zawiya and Tripoli as well as Tripoli International Airport.

Tripoli Security Directorate – The Tripoli Security Directorate are a unit part of the GNA interior ministry. They have set-up checkpoints in various areas of Tripoli, such as Hay al Andalus, Gurji, Al Nasr street, Airport Road and Aziziyah. They and other interior ministry and security directorate units such as Central Security and the CID, have carried out arrests of those responsible for kidnap, robbery/theft and murder, however, their power is dwarfed by that of militias. Security directorates – not just in Tripoli – frequently carry out campaigns targeting vehicles with tinted windows or with no number plates. Those using such vehicles are usually involved in kidnapping, murder and other criminal activities.

GNC-Affiliated Militias – In May, Libya Herald reported larger GNC-affiliated militias mostly from western Libya withdrew from Tripoli to its outskirts and smaller, irregular units remained in Tripoli, according to Khalifa Ghwell. The major militias, such as the Kani Brigade (now active mainly in Tarhouna, Garabulli and Souq al Khamis) and Amazigh-led Mobile Forces (previously active mainly in Janzour and Gurji), withdrew to Zawiyah, Sabratha and Tarhouna. Misratan militias, meanwhile, withdrew to Misrata. Large quantities of weapons and ammunition were reportedly moved out of Tripoli to Zawiyah.

In early December, The Guardian reported that Saif Gaddafi intends to make a return to the political scene and is leading a military campaign against ‘terrorist groups’ around Tripoli. His force has taken control of Sabratha. To what extent this is true, especially with regards to the military campaign he is supposedly leading, remains to be seen. The Counter/Anti-IS Operations Room is currently in control of Sabratha after they defeated the Dabbashi Battalion and its sister group: the 48 Battalion. The ops room was created by the Presidency Council to combat the threat of IS.

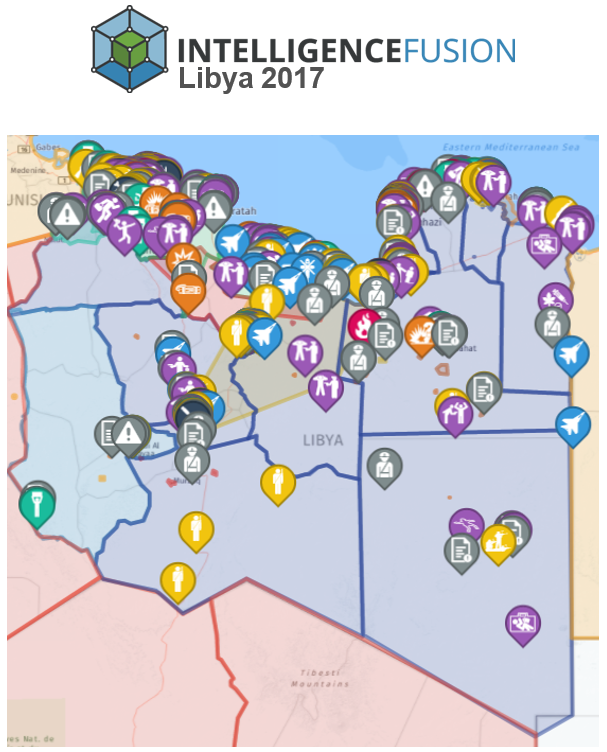

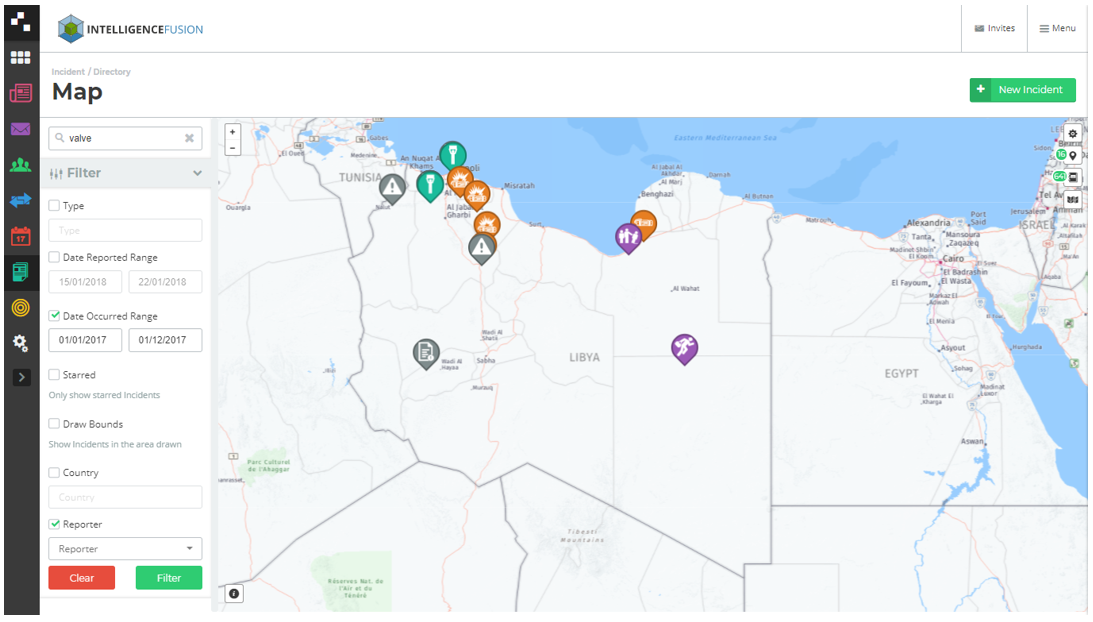

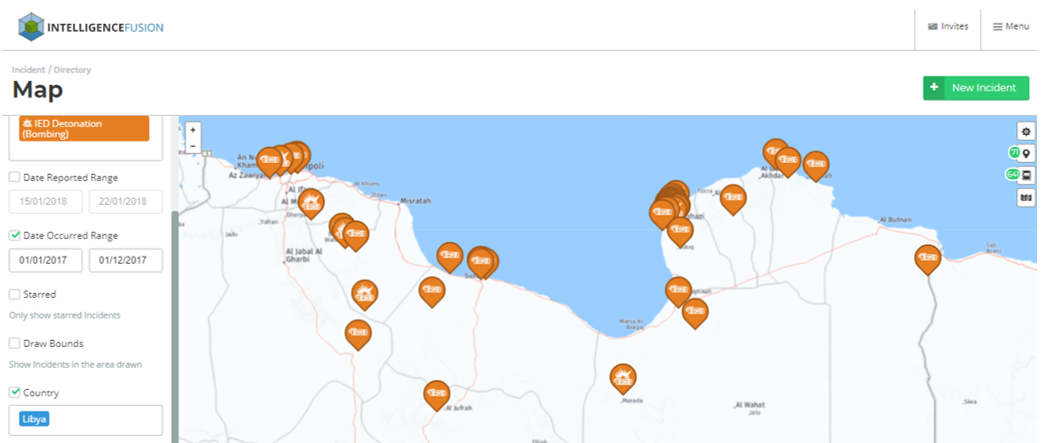

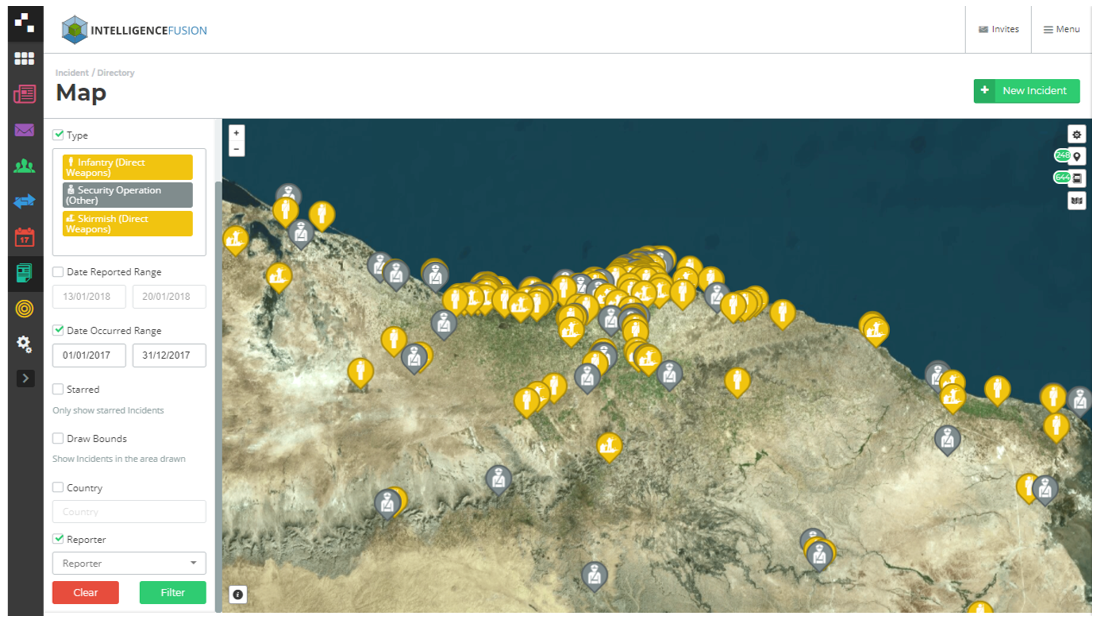

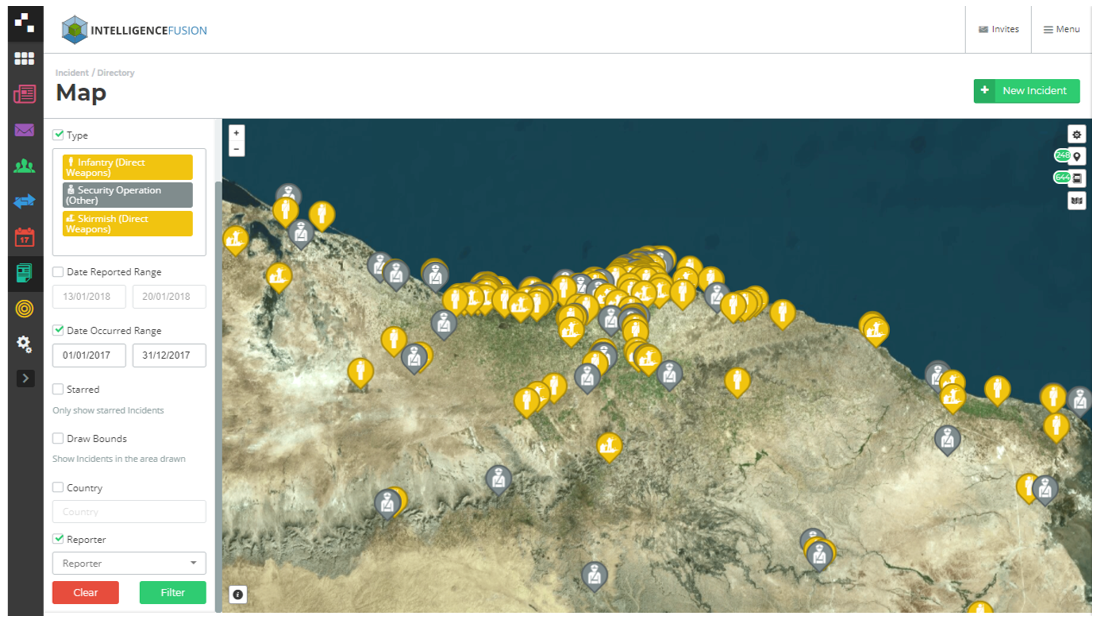

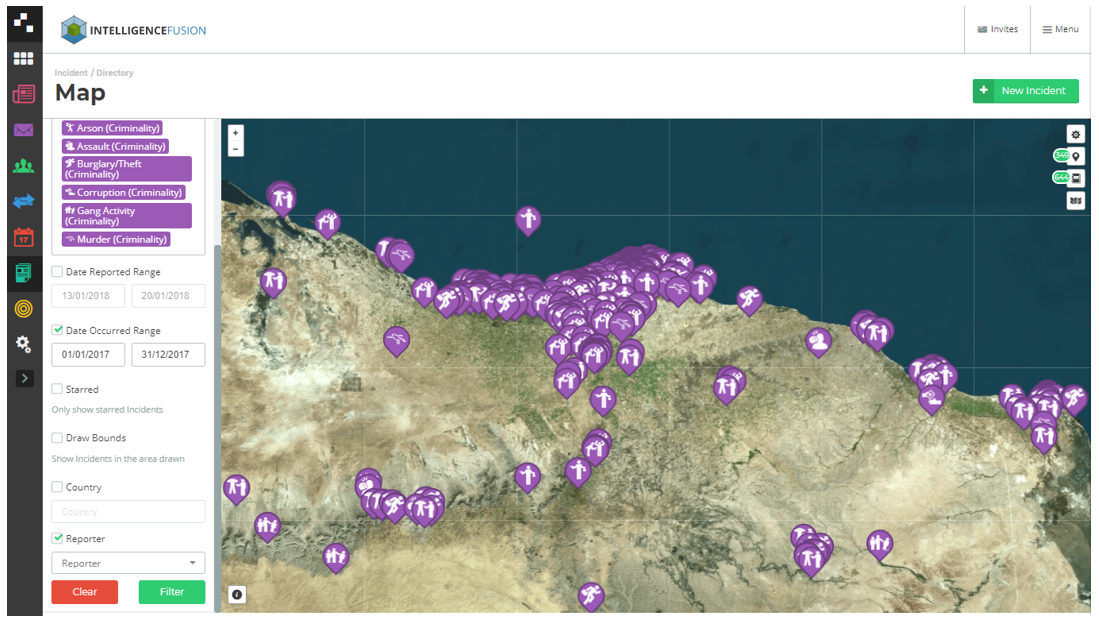

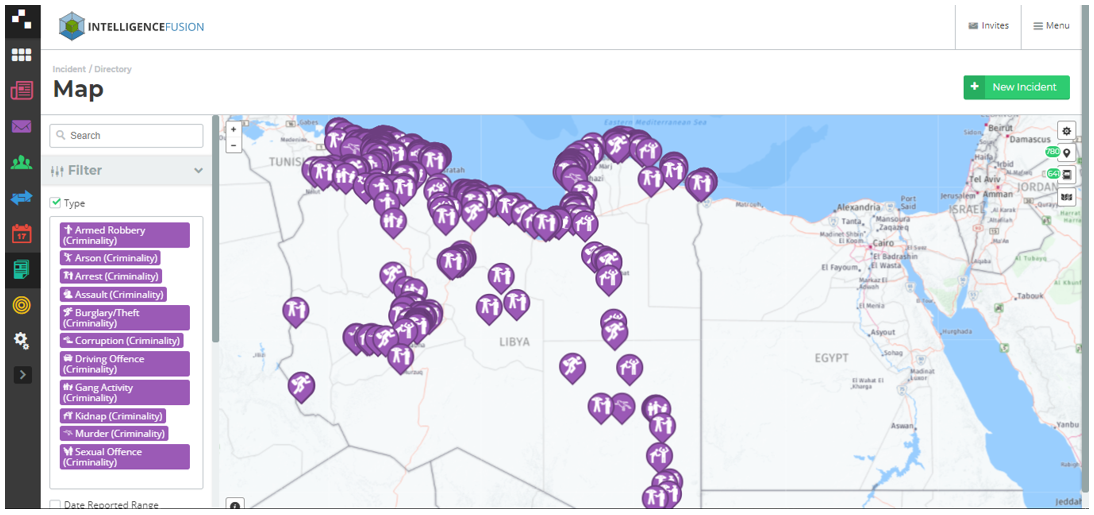

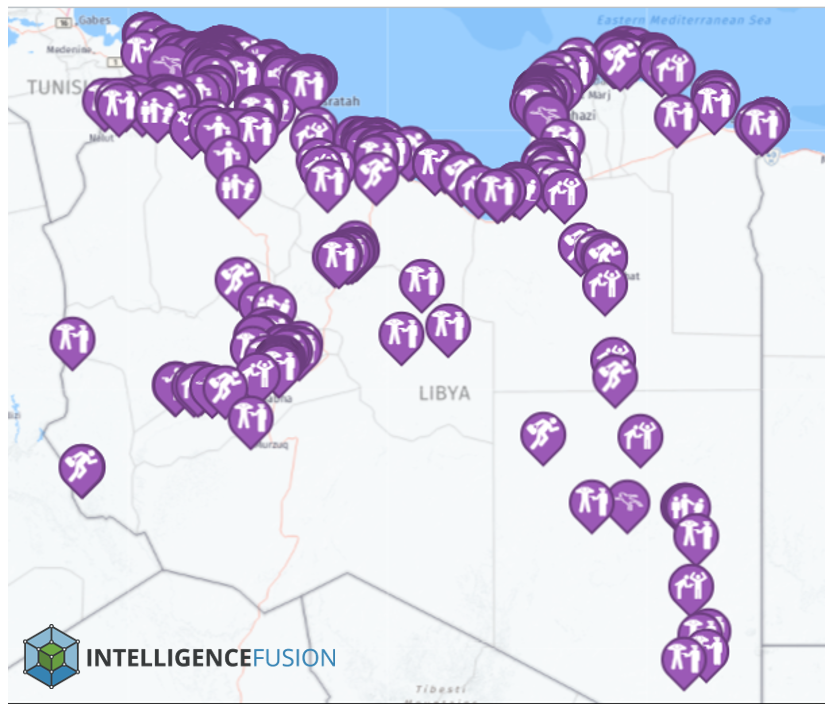

Skirmishes between militias have claimed hundreds of lives in Western Libya and have affected the lives of many more. Armed groups or sometimes demonstrators (see picture below of selected incidents) also often close or sabotage oil/gas/water valves or attack electrical infrastructure, block roads usually in protest against, for example, load shedding (power outages), marginalisation (real or perceived), non-payment of salary or in protest against an arrest thereby exacerbating living conditions and development. Criminal groups usually target electrical infrastructure to extract copper and/or other metals.

While the threat of terrorist attacks or sabotage in the oil crescent region has not subsided, the NOC is eager for oil production to rise.

Benghazi

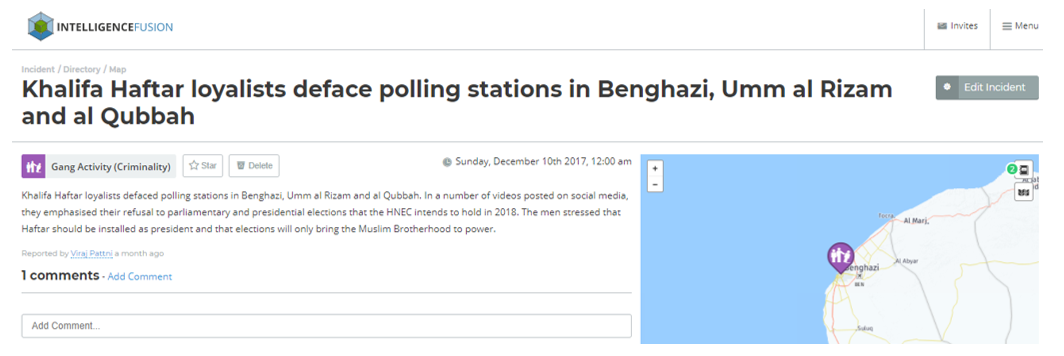

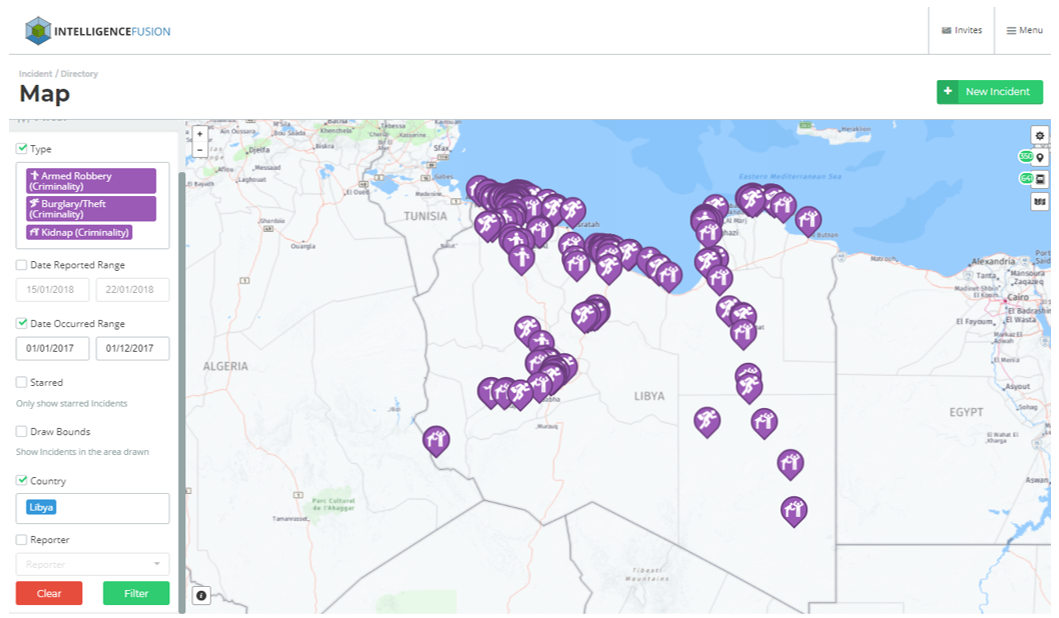

The LNA and Saiqa Special Forces defeated remaining BRSC militants from Sabri and Souq al Hout, and lastly in Sidi Khrebesh and around the municipal hotel towards the latter end of 2017. However, the crime rate, specifically kidnap for ransom and armed robbery, has increased as fighting between the LNA and BRSC has slowly dissipated over the past few months. Reports state there were 45 armed robberies in the first week of November alone. It is believed many young men part of the LNA have turned to crime for financial income. The self-proclaimed Field Marshal and Head of the LNA, Khalifa Haftar, issued instructions for a central operations room to be set up to combat crime. The LNA western military governor and chief of staff, Major General Abdul Razzaq Al-Nazhuri, has also vowed to crackdown on crime in Benghazi. The Saiqa Special Forces are playing a leading role in policing and securing Benghazi. Wanis Bukhamada, Commander of the Saiqa Special Forces, has been placed as the head of the central operations room. Others part of this inter-agency coordination room include: Brigadier Mohamed Al Magrous, the head of military intelligence, Brigadier Ahmed Salem of the Control Commission, Colonel Faraj Al-Zbu, head of the military police and military prisons, and Colonel Salah Huwaidi, the former head of Benghazi security directorate and still head of criminal investigation authority (CID) in Benghazi.

Other notable incidents in Benghazi include the systematic arrest, torture and extra-judicial killings of individuals some of which are known to have opposing political views.

At least one family, whose member was identified as one of the victims, said the Tareq Bin Zayed Brigade – said to be Madkhali Salafist unit – was responsible for his kidnap.

Many bodies of kidnapped individuals have been dumped on Al-Zayt Street in Benghazi.

Islamic State

Since Al Bunyan Al Marsus (BAM) forces took control of Sirte in December 2016, BAM affiliated forces have taken on the role of securing the city. The 604 Battalion are securing central Sirte, while Misratan forces are securing the entrances of the city. Earlier in the year there were reports of tension between the 604 Battalion and Misratan forces who suspected the former (a Madkhali Salafist unit trained and equipped by RADA SDF in Tripoli) of cooperating with the LNA. According to the UN Panel of Experts 2017 report, the battalion’s emir made several trips to Al Bayda and warned the Muslim Brotherhood and armed groups associated with the now defunct LIFG not to opening a second front against “forces of the east”. Since its liberation from IS, BAM security forces have been unable to effectively assert their authority, and theft and armed robberies have been rife. Forces securing Sirte have called on the Presidency Council to provide them with ‘resources’ to enable them to carry out their duties more effectively. There have been several demonstrations with residents of destroyed neighbourhoods, of which there are more than two thousand families, demanding financial aid to pay for temporary relocation and/or rent, for bodies of dead IS militants to be recovered and the acceleration of the clean-up operation, redevelopment of destroyed neighbourhoods and for safety and security to be restored.

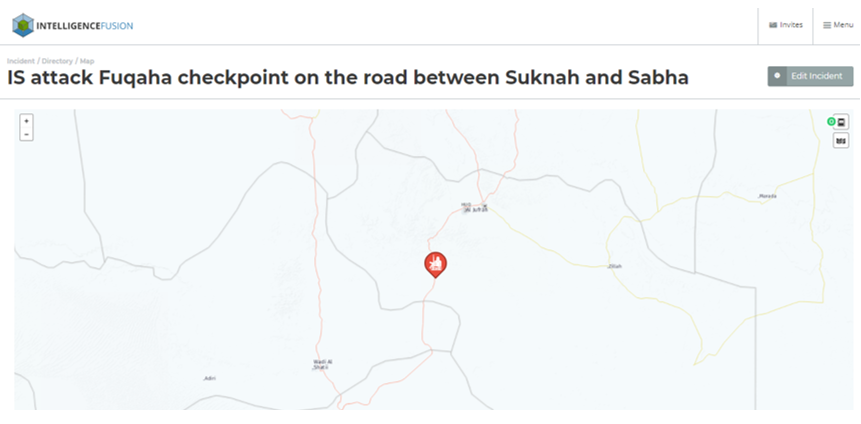

There have been consistent reports of IS setting up fake checkpoints on the Jufra-Sirte road, two separate reports stated fake checkpoints were set just 17 and 20 km south of Sirte, and on the Abugrein-Sirte road. An IS propaganda video in August 2017 purports to show an IS checkpoint between Abu Grein and Jufra. During interrogation, the two recently arrested IS members who attempted to detonate a VBIED claimed they arrived in Tripoli from the desert regions near Sabha where their orders were received. In 2017, U.S. airstrikes targeted IS camps south of Sirte and near Fuqaha, a checkpoint IS attacked on 23rd August 2017.

The Libyan Attorney General, Sadiq As Soor, in a press conference said Mahmoud al-Barasi and Hashim Abu Sidra are members of IS that escaped Sirte to the desert area. At the time of the press conference, Soor said they were alive. It is unclear if they have since been killed by USAF airstrikes. Up to 830 arrest warrants have been issued for suspects linked to IS in Libya, a further 50 arrest warrants have been issued for suspects outside of Libya – a list that has been handed over Interpol.

An infographic released by the BAM operations room showing the numbers of foreign fighters that joined IS in Libya. Over 100 each from countries in the top tier, between 50 and 100 each from countries in the second tier, between 10 and 50 each from countries in the third tier and between 1 and 10 each from countries in the fourth tier. Maps below, also released by the operations room, show routes IS fighters/recruits took into Libya.