Key Threats To the Future of the Afghan Government

Part 1: The Taliban and Funding (Posted 2nd May)

Part 2: The Rising Influence of the Islamic State in Afghanistan (Posted 3rd May)

Part 3: The Weakness of Centralised Government (Posted 4th May)

Part 4: Threat Posed by External Actors and Conclusion (Posted 5th May)

Introduction

The future of Afghanistan looks to be a lot like its past, difficult, violent and charged by foreign intervention. The Taliban, who were weakened by the NATO combat operations which concluded in 2014 have been able to significantly increase their position within the country in the absence of strong governmental influence across the country. The revival of the Taliban has been accompanied by the formulation of the Islamic State of Korosan Province, who whilst affiliated with the more contemporary ISIS still represent a continuation of the tribal conflict which has featured so heavily in Afghan history. The National Unity Government (NUG) fight a desperate conflict against well funded, well equipped and powerful insurgencies. To further complicate Afghanistanâs already difficult position, Afghanistanâs neighbours grow increasingly concerned about the insecurity emanating from the country and have used this to justify their often unwelcome input in the country. This piece will aim to highlight and explore four of the most prominent threats which contribute to the growing insecurity in Afghanistan since the end of NATOâs combat operations. As long as these threats, identified as the revival of the Taliban, the rise of IS-KP, the poor performance of the NUG and the input of foreign states are permitted to continue, violence and instability will prevail in Afghanistan.

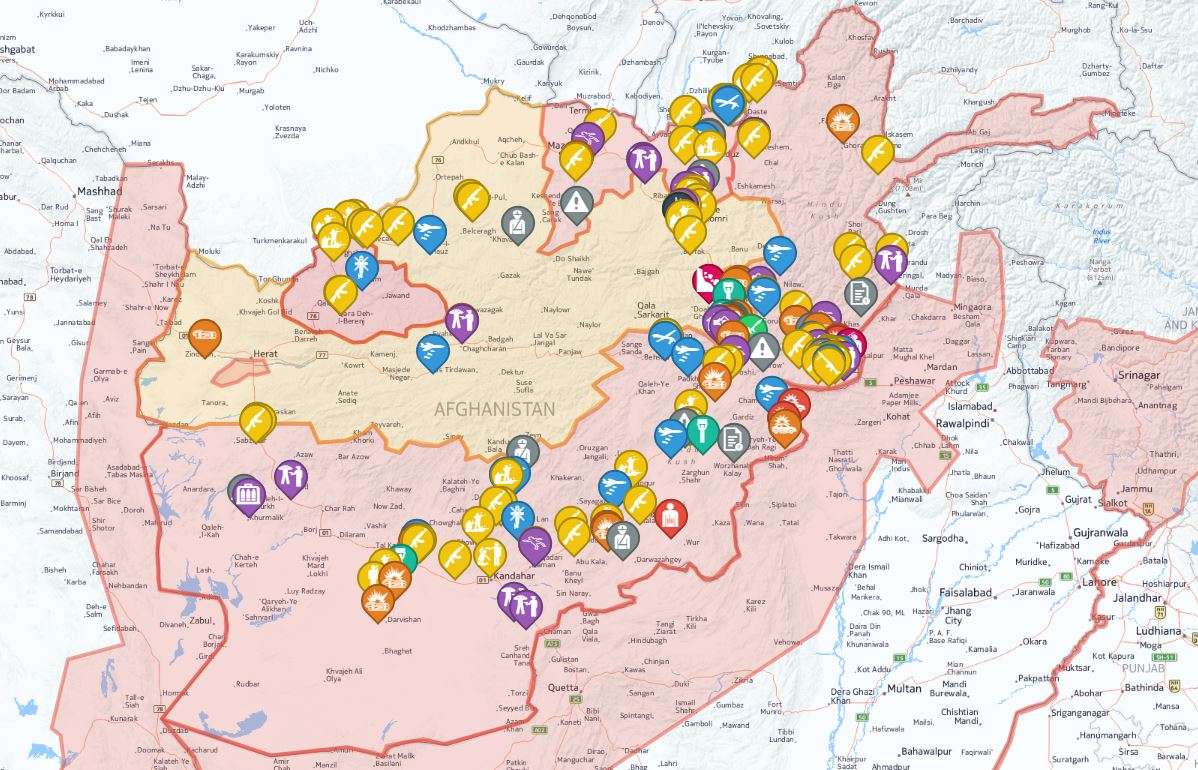

Afghanistan Incident Map – Past 30 days.

Part 1 – The Taliban

Since the Taliban regime was toppled in 2001, the group has managed to remain a potent threat. Between 2001 and 2014, when NATO combat operations were taking place the insurgency was suppressed but by no means permanently. Throughout the period, the Pashtun Taliban were able to maintain a strong enough position in the rural areas of the largely Pashtun Helmand and Kandahar provinces as well the provinces which border the porous Pakistan-Afghan border. It is from these provinces that the Taliban have been able to launch themselves into their revival. Despite heavy losses inflicted by security forces, with some estimates claiming that the Taliban lose 12 fighters per day,[i] the group has been able to grow at an alarming rate since the end of NATO combat operations in 2014 and is deserving of the title of a major security threat in Afghanistan.

Contrary to much of the rhetoric coming from government sources, the Taliban enjoy an element of passive support in their home provinces. A study conducted by the Asia Foundation found that the Taliban heartland of South Western Afghanistan has the highest amount of sympathy for the anti-government groups. The study showed that 13% of those polled had âa lot of sympathyâ for anti-government militants and 37% had âa little sympathy.â[ii] These figures stand in stark contrast to those who were polled in the area around Kabul, where just 5% claimed to have a lot of sympathy and 15% had a little sympathy. With this sympathy to their cause, the Taliban have been able to use the southern provinces as a base of power. Taliban support does not necessarily occur due to people agreeing fully with their fundamentalist interpretation of Islam (although this does attract some.) Instead, many are simply tired of the constant instability that their country has seen and the Talibanâs reputation for swift justice and organisation acts as a pull factor. Regardless of the reasons for support, the Taliban were able to further consolidate their influence in the already sympathetic provinces after they captured Sangin in March 2017[iii]. Despite US and Afghan attempts to evacuate the district centre and reposition it, the damage was done. Taliban militants were pictured driving vehicles stolen from the abandoned security forces positions along with captured weapons.

The Taliban currently remains a largely rural insurgency, but it has begun to set its eyes on urban population centres in the form of provincial capitals. In Kunduz in the North of the country, the Taliban have been able to utilise the insecurity to their advantage. As well as Kunduz and other Northern provincial capitals, Lashkargah and Kandahar seem likely to be the next targets for the Talibanâs offensive in the Urban areas. The seizure of Lashkargah would give the insurgency nearly total control of the Province of Helmand, which would not only be a physical victory but also a highly symbolic one. Each capture of a security forces position or a district centre highlights the Talibanâs power, and further adds to the impression that the security forces are losing control. Ascertaining exactly how much of the country the Taliban control comes with inherent difficulties, as all sides are unwilling to admit lack of control. Not only this, but the actual definition of control is difficult to define, as varying levels of control exist across the country. However, FDDâs Long War Journal published an interpretation of Taliban claims of control, which highlighted an alarming ability of the Taliban to project their influence across the country.[iv]

The command structure of the Taliban is relatively centralised, and is currently led by Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada. The commander has 2 deputies, appointed in 2015 called Mawlawi Haibatullah Akhundzada and Sirajuddin Haqqani (the son of the Haqqani Networks founder.)[v] The Quetta Shura represents the next tier, and is a council made up of numerous Taliban clerics. The tier below the secretive Quetta Shura is the Taliban Shadow Government. The Talibanâs shadow government lends them an air of legitimacy, and serves to portray the Taliban as a government in waiting. However, the centralised nature of the Taliban command structure has left it vulnerable to targeting from US drone strikes, as the removal of a major player has in the past led to infighting. The targeted killing of the Taliban commanders has also served to exasperate differences in opinion regarding whether or not the group should engage in talks with the government. This has been one of the most prominent reasons for infighting within the group, and the issue comes to the front when selecting new regional commanders.

Taliban tactics inevitably vary, with the IED which characterised the 2001-2014 NATO operations being a mainstay in the Taliban arsenal. Suicide bombings have also featured heavily and, as the Taliban have frequently targeted government workers, buildings and officials. Some of these attacks have been filmed by commercially available drones, with the video featuring in their recruitment videos. The Taliban have also committed to infiltrating the ranks of the Afghan security forces, and using their insiders to launch attacks on security forces positions. A prominent example being in April 2017, when the Taliban launched a coordinated suicide attack on the 209 Shaheen Corps HQ near Mazar-I-Sharif. The attack was conducted by militants in security uniforms and vehicles. Estimates put the casualty figures of the incident as high as 130, many of whom were praying and unarmed during the incident. The attack carried more significance still, in that the Taliban claimed that the attack was launched in response to the killing of a high profile commander in an air strike in Kunduz. As attacks on the Talibanâs command structure continues, and if Taliban rhetoric is to be believed then attacks such as this may continue.

Taliban recruitment and propaganda shows an attempt to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the people of Afghanistan in an attempt to broaden its support base. Frequent references to civilian deaths as a result of security forces attacks have featured on Taliban social media and in the annual Eid al-Fitr statements, with the intention being to portray themselves as more legitimate than the NUG. The Taliban have also attempted to soften their image somewhat, and as part of this the group has claimed that it will protect aid workers and other personnel who are key to improving the welfare of Afghan people. This attempt to win over support is not necessarily new though, as in 2006, Mullah Omar – the groups commander at the time â called for Taliban commanders to use their discretion in implementing some of the draconian measures which have characterised the insurgency. More recently, as part of the Talibanâs drive to increase its soft power the Taliban called for people of Afghanistan to plant more treeâs for âworldly goodâ as part of an attempt to soften their image.[vi] However, much of this is simply rhetoric aimed at appealing to a broader audience, as attacks on aid workers and government officials continue seemingly unchecked.

The Talibanâs current trend of expansion seems set to continue in the face of a weak government which has been plagued by corruption and lack of funding. It seems unlikely that the Taliban will be able to seize total control over Afghanistan, as important urban areas such as Kabul lack the sympathy towards the Taliban cause that can be observed in Helmand and Kandahar. US air assets have also supported the Afghan security forces, targeting the centralised command structure and generally causing problems for the insurgency. It is hard to imagine that the USA and their NATO allies are prepared to let Afghanistan sink back into Taliban hands after so many lives were lost. Therefore as the Taliban presents itself as a greater threat to the NUG, the USA will see it as a greater threat to their regional interests, particularly in the face of alleged increased Russian influence. It seems likely that the USA will respond with an extra commitment of air assets and soldiers in a training role in the face of a revived Taliban insurgency.

Taliban and Funding

Whilst the Taliban traditionally use fairly low-tech methods as part of their insurgency this is not to suggest that they are short on money, as the situation is quite the opposite. The Taliban have funded their activities through a mixture of domestically sourced funding, such as agricultural taxes as well as extortion, protection and strong connections with drug smuggling. The Taliban can also rely on funding from private foreign donors, in particular from Pakistan, UAE, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Lastly, the Taliban have allegedly been supported by the Pakistani intelligence services as part of their attempt to retain influence in the region, and with this comes additional funding and weapons.

The Taliban have levied taxes on the farmers of Afghanistan, referred to as the Ushr tax. This tax is normally a 10% tax on farmers, and refusal to pay or inability to pay leaves the farmer in question at the Talibanâs mercy. However, many choose to pay the tax because they do not feel the security forces can protect them if they choose to deny the Taliban their funding. In addition to the often unpopular Ushr tax, the Taliban can also call upon the Zakat tax to fund their insurgency, which is a 2.5% tax on wealth. Regardless of its unpopularity, both of these taxes are rooted in Islamic tradition, and therefore carry an air of legitimacy.

Extensive studies have been made regarding the impact of opium production on the Taliban insurgency, with Gretchen Peterâs being particularly comprehensive.[i] Whilst the NATO combat operations committed considerable time to reducing the amount of poppyâs grown in Afghanistan, it has still been able to thrive. In the largely Taliban controlled South, poppy fields thrive in abundance. Poppy crops not only sell for higher prices than many essential food crops, but they can also be stored for longer. Authorities have found it hard to convince farmers to move away from the highly profitable and reliable poppy crop (and also unwilling in many cases due to personal connections with the drugs trade.) The Taliban are able to use their considerable influence in the Southern provinces to control the drugs trade, and gain huge profits from trafficking opium across the southern border into Pakistan. Drug smugglers may either work directly for the Taliban, or are expected to pay for protection whilst operating in Taliban controlled areas.

External funding from foreign donors has helped to prop up the Taliban and fund their revival throughout and since the end of combat operations. Some of this money has come from Islamic charities, but the impact of these groups funding on the Talibanâs activities has been hard to gauge. As well as individual donors, The Taliban have also enjoyed significant support from Pakistanâs ISI. The discussion surrounding Pakistani support for the Taliban has been littered with claims made all sides involved with the conflict in Afghanistan, all of which are hard to verify.

Pakistani support for the Taliban insurgency is part of the larger Pakistani regional policy which focuses around maintaining influence and suppressing potential rivals. Pakistan knew that the US would have to leave Afghanistan at some point, and maintained support for the Taliban so that they would still have influence after the departure of western forces. Financial support is not the only type of support offered to the Taliban by Pakistan, and nature of Pakistani support will be explored later in this piece.

Part 2 – The Rising Influence of the Islamic State in Afghanistan

The Islamic State of Khorosan Province, as they have come to be known in Afghanistan have grown into a significant threat to the security of Afghanistan. Whilst IS-KP may be affiliated with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, they still retain relative autonomy in their actions. At first sight the affiliation with the more contemporary ISIS group may suggest that IS-KP are an entirely new threat in Afghanistan, but they also represent a continuation of tribal conflict. The extreme violence which characterised the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria features within IS-KPâs tactics too, and this serves to render them a significant threat to security in Afghanistan. On paper, the insurgency waged by IS-KP is not destined to be successful, with a reliance on foreign fighters, a vision of Islam which alienates potential supporters and relatively small numbers but the chronic insecurity has allowed them to grow and gain a foothold in the country.

The majority of the IS command structure in Afghanistan is made up of former Tehrik-I-Talibani militants, many of whom belong to the Orakzai sub-tribe of the Pashtun. The Orakzai traditionally reside in the FATA across the border in Pakistan and have fought against the Taliban and Al Qaeda before. After factions of the Tehrik-I-Talibani swore allegiance to IS, they brought with them scores of disgruntled Taliban fighters, with some frustrated by talk within the Taliban of negotiations with the government. IS-KP has also been able to recruit from other central Asian countries, with the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) swearing allegiance and swelling the ranks of IS-KP. The reliance upon fighters from outside of Afghanistan has damaged the appeal of the group in a country which hosts a traditional mistrust of foreigners, but the security forces have struggled to capitalise on this and the group continues to exist.

An IS-KP offensive in July 2015 saw the group take control of 8 districts in southern Nangarhar Province. IS militants burnt the homes of Taliban and government supporters and generally terrorised civilian groupings which opposed them. Other members of the Orakzai tribal grouping are reported to have since occupied the territory captured by IS as part of an attempt to cement their control. Since the offensive, IS control in Nangarhar has been reduced to just four districts, with the most violent being the Haska Mina district and the Achin district, where the US dropped the MOAB in April 2017. The rise of IS in Afghanistan has been hindered by 2 significant checks in the form of increased US attention and opposition from the Taliban. US drone strikes and air strikes have largely targeted IS militants in Nangarhar, but without an effective counter-insurgency and reconstruction campaign on the ground, this has not been sufficient to prevent IS from rising and only represents a short term fix. With this in mind, the recent MOAB strike, whilst claiming the lives of numerous IS militants is not sufficient to defeat the group on its own. Opposition from the Taliban forced IS-KP out of Helmand in 2015 and continues to slow the rise. However, fighting between IS and Taliban militants only serves to add to the insecurity, further paving the way for militancy and lawlessness.

Currently, IS-KP seem poised to expand further, albeit tentatively and slowly. IS recruiters and recruitment leaflets have been arrested and seized in Kunar, Ghor and across the North of the country. In Northern Afghanistan, the security forces are supported by the pro-government Junbish militias. The militias are largely made up of the remnants of the former Northern Alliance, and therefore have significant manpower and resources. Whilst the militias are affiliated to the government, they are known to use their positions of power to further the political interests of their commanders. The militias have been involved in numerous cases in which they have abused civilians and their combat efficiency has been questioned. Infighting between various branches of militias affiliated with political parties have seriously affected their ability to combat the rising insurgencies. IS-KP have been able to increase their influence in the north in the face of such weak security forces, and incidents involving IS across these regions have begun to increase.

Whilst IS-KP already represent a significant threat to the government, many fear that their strength will increase as ISIS is pushed back in Iraq and Syria. As the group gradually loses territory across the Levant, militants may move to Afghanistan to try and rebuild their Caliphate or alternatively use Afghanistan as a safe haven for ISIS to regroup and recover. The increased manpower that this could potentially bring to IS-KP would give the group the power required to expand into already unstable districts in the North of the country. Whilst one can expect the Taliban to actively try and combat the rise of IS-KP, fighting between the two groups only serves to add to the insecurity in the country, and further open the door to militancy and lawlessness.

Part 3: The Weakness of Centralised Government

Politics in Afghanistan is intimately linked with the complex tribal network that has dominated the countries history for centuries. Particularly in the rural areas, tribal and religious considerations often come before government. The reasons for this vary depending on the individual in question, however lack of governmental influence outside of the major urban population centres has given very little incentive to follow governmental law. The difficulties of maintaining Ghaniâs centralised government in Afghanistan is further compounded by chronic corruption and infighting which seems to have gone unchecked since the government was put in place. Ghaniâs predecessor, Kharzai has in hindsight been accused of allowing corruption to thrive in his government, leaving the current government plagued by it. Recent events within Afghan politics have highlighted the volatility and complexity of Afghan politics, and have allowed the revival of insurgency across the country.

Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum, former general within the Northern Alliance, has been involved in an episode which has significantly harmed the integrity of the NUG. In November of 2016, some of Dostumâs men abducted a political rival at a game of Buzkashi and were accused of illegally imprisoning and sexually assaulting him. The incident posed a significant problem for the NUG, as Dostum, founder of the Junbish political party still wields considerable power in the form of armed militias who answer to him, protecting him from the will of his own government. The situation took a turn into a potentially volatile situation, in which police officers lay siege the Dostumâs compound in downtown Kabul, which was protected by militia loyal to Dostum. The episode represents many of the difficulties which face the NUG, in that as long as the centralised government struggles to extend its influence across the country, it is reliant upon warlords such as Dostum to maintain security. To alienate such power holders would leave powerful militias outside of the political process with very few options but to utilise the large arsenals under their control. Therefore, the current NUG, much like previous governments is held together by a fragile coalition of tribal and ethnic considerations in which militiaâs with very little official oversight wield considerable power.

The vast majority of security forces operations are conducted by the ANA (Afghan National Army.) The ANA is supported by the Afghan National Police as well as border police and a small Afghan Air Force. Much like the government though, the security forces face ingrained corruption amongst high ranking commanders, lack of funding as well as tribal and ethnically fuelled infighting. The Afghan security forces have struggled to gain recruits from the Pashtun dominated provinces, and the majority of its soldiers are Tajik, Uzbkek and other groups from the North. In a situation somewhat unique to Afghanistan, the security forces therefore are seen as largely foreign to those outside of the northern provinces, undermining their counter-insurgency operations.

Despite NATO soldiers staying behind after 2014 to assist the training of the Afghan Army, its quality has varied dramatically. Some Afghan commanders have been highly professional and effective, whereas others have used their positions of power fairly poorly. Commanders at all levels in the military have been accused of being involved in the illegal drugs trade or having interests outside of the army itself. Despite huge amounts of money being spent on training, the casualty figures amongst the security forces have been alarmingly high. One estimate, created by a US government monitoring agency claimed that the Afghan security forces took 15,000 casualties dead and wounded in the first months of 2016.[i] In the face of mounting casualties, recruitment has been difficult.

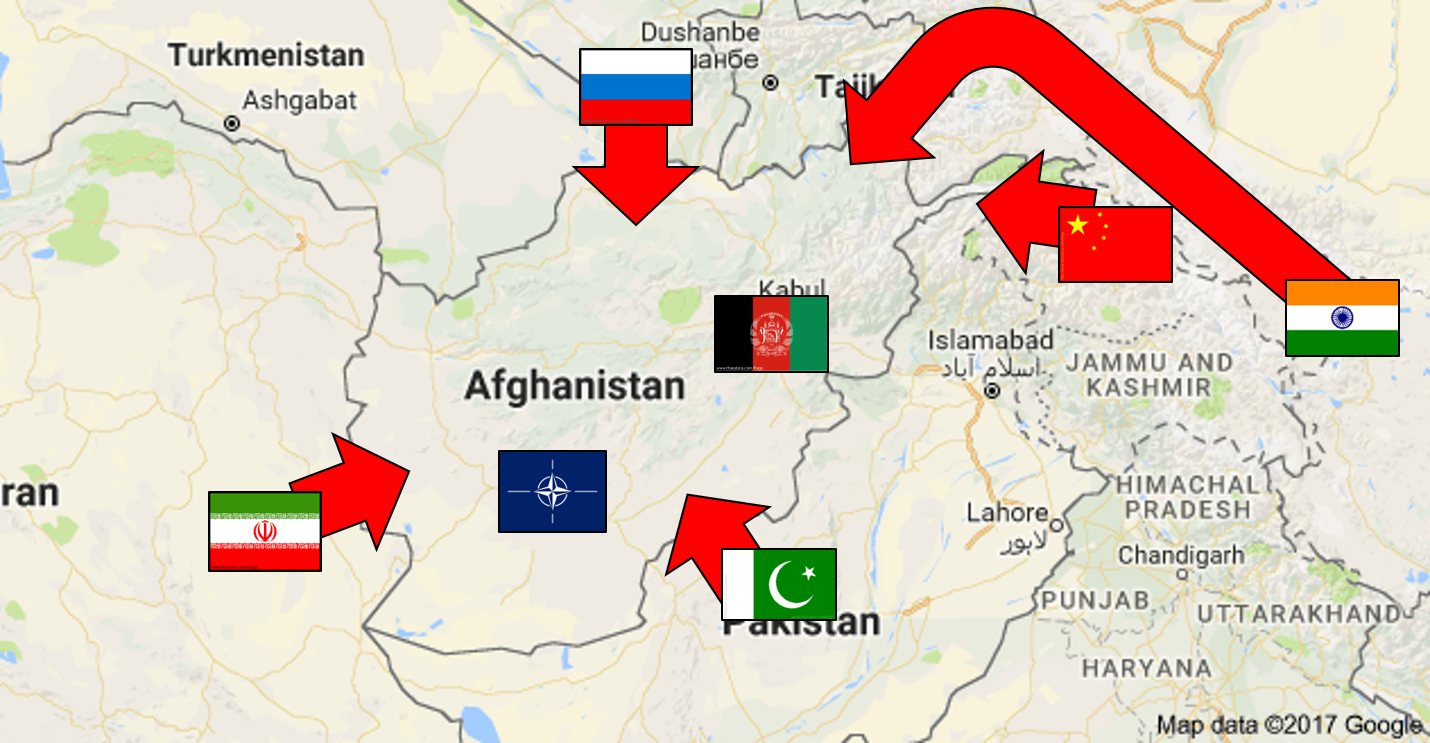

Part 4: Threat Posed by External Actors

The USA and the countries of NATO are not the only countries with strategic interests in Afghanistan. Pakistanâs connections with the Afghan Taliban, whilst not formally acknowledged is a well known part of Pakistanâs policy in the area. However, the level of control which Pakistan has over the Taliban is hard to gauge, and the relationship seems to be largely restricted to financial and logistical support. More recently, both US and Afghan politicians and Military commanders such as US National Security Advisor H. McMaster have accused the Russians of providing support to the Taliban, which the Russians have strongly denied. Less intrusive, but still topical Chinese troops are also reported to have been spotted patrolling in Afghan territory, but these claims were also rejected and have not been verified.

Pakistani support of the Taliban fits neatly within its policy of supporting extremist groups which support its foreign policy goals, and utilising them as a proxy. During the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, Pakistan was heavily involved along with the US in supporting the Mujahadeen opposed to the Soviets, and support of the Taliban largely represents enduring Pakistani interests in the region. An age old disagreement regarding the legitimacy of the Durand line has led to Afghanistan frequently calling for Pakistan to hand over territory given to Pakistan as part of the agreement made in 1919. Therefore, analysts speculate that Pakistan does not wish to allow an Afghan government to become strong enough to be able to make a serious challenge to the Durand line. Interestingly, despite Pakistani support the Afghan Taliban have refused to accept the legitimacy of the Durand line which divided Pashtun territory which highlights that Pakistanâs influence over the Taliban is far from total. The ease with which militants cross between Afghanistan and Pakistan is unlikely to change, as relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan seem to be more strained than usual. Pakistan shelling across the border into Afghanistan has fuelled increasingly powerful anti-Pakistan rhetoric from politicians and civilians alike. Therefore, regardless of the amount of international pressure placed on countries to cease support for militants in Afghanistan, it is unlikely that Pakistan will cede its influence in the potential proxy war which faces Afghanistan.

Russian support for the Taliban has been somewhat more controversial. Russia does not entirely deny any connection with the Taliban, and insists that it only maintains contact with the Taliban in order to assist in bringing them to negotiations with the government. However, US Gen. John Nicholson claims that Russia has provided light and medium weaponry to the Taliban.[i] Russia has also referenced the instability which reigns in Afghanistan in order to justify its involvement, particularly in the face of a rising ISIS influence in the country. Russiaâs claims that the influence of IS-KP motivates their involvement is somewhat impotent, as local media has claimed that Taliban officials have claimed to have been supported by Russia since 2007, before IS-KP were a threat in the country.[ii] With the Russians staunchly denying any support for the Taliban, their motivation is hard to gauge, but it currently it seems as if Russia is cautious in allowing a government friendly to the USA to thrive in the region.

Conclusions

It is important to see Afghanistan as part of a larger strategic picture in order to comprehend what motivates foreign countries influence in the struggling country. With this said, the current challenges to security and stability are firmly rooted in Afghan tradition and history. Bringing the era of conflict, violence and insecurity to an end therefore, will require a strategy which can address the internal conflict of Afghanistan that has been spurred on by the influence of foreign states. The NATO operations of 2001-2014 largely struggled to tackle these issues, and insecurity remains prevalent in Afghanistan. Since 2014, the Taliban have risen and have extended their influence across the country, gaining district after district and further undermining the ability of the NUG. The problems posed by the rise of an increasingly aggressive Taliban insurgency have been further compounded by the additional influence of IS-KP. Neither the Taliban nor IS-KP wield universal support across the country, yet they have been able to rise since the end of combat operations in the absence of any significant influence from the centralised government. In countering the insurgencies, the Afghan security forces have struggled, despite residual support from US and NATO forces since 2014. The northern dominated Afghan Army therefore, does not have the strength or the legitimacy required to counter the threats which face the already vulnerable country. Looking into the future, it is unlikely that the Afghan government will be able to deal with the multiple threats facing it without substantial support from other countries and therefore, it is reasonable to assume that Afghanistan will see more instability and violence in the years to come.

[i]http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/russia-taliban-arming-fighters-afghanistan-weapons-us-officials-a7700806.html

[ii]http://www.breitbart.com/national-security/2016/12/09/report-taliban-russia-combat-us/

[i]http://www.voanews.com/a/afghanistan-us/3571779.html

]http://www.voanews.com/a/despite-massive-taliban-death-toll-no-drop-in-insurgency/1866009.html

[ii]http://afghansurvey.asiafoundation.org/how-much-sympathy-do-you-have-for-anti-government-groups#2014

[iii]http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2017/03/taliban-takes-key-district-in-helmand-province.php

[iv]http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2017/03/afghan-taliban-lists-percent-of-country-under-the-control-of-mujahideen.php

[v]http://www.cfr.org/terrorist-organizations-and-networks/taliban/p35985?cid=marketing_use-taliban_infoguide-012115#!/p35985?cid=marketing_use-taliban_infoguide-012115

[vi]http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-27/taliban-leader-urges-afghans-to-plant-more-trees/8305388

[vii]https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/taliban_opium.pdf

[ix]http://www.voanews.com/a/afghanistan-us/3571779.html

[x]http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/russia-taliban-arming-fighters-afghanistan-weapons-us-officials-a7700806.html

[xi]http://www.breitbart.com/national-security/2016/12/09/report-taliban-russia-combat-us/