Kenya’s Struggle with Climate Change and Flooding

Floods in Kenya in 2018: March to May

While Kenya has made important strides in recognising the threat of climate change – in fairness a global threat which requires an effective global response – to its development, the recent floods have exposed areas of vulnerability and gaps in disaster preparedness, mitigation and response.

Disaster management in Kenya has been, in the past, described as reactionary. Following the El Nino rains more than twenty years ago, the government established the National Disaster Operations Centre (NDOC) is an inter-agency command centre to coordinate disaster response efforts. The founding of the NDMA (National Drought Management Authority) after droughts in 2011 is also a case in point. In 2013, the NDMU was created. Its mission, as stated, is ‘to effectively prepare for and respond to disasters and emergencies, manage recovery and mitigation efforts in Kenya in collaboration with other stakeholders in order to save lives, minimize loss of property and to protect the environment.’

The NDMU is part of the Kenya Police Service and is also tasked with coordinating disaster management and collaborating with various institutions and ministries, UN agencies, INGOs, NGOs, CBOs, FBOs, communities and others. County-level NDMU structures have also been established. The unit’s activities are guided by an emergency response plan and SOPs that provide a strategic, operational and tactical guide to all phases of disaster management.

Finally, The government, through the formerly known Ministry of State for Special Programmes, has also developed National Policy for Disaster Management in Kenya and National Disaster Response Plan to guide in the disaster risk reduction. Other Kenyan institutions such as the KDF, NYS, KPLC, KeNHA and other institutions also assist with disaster management. NGOs such as the Red Cross and other play a key role in disaster response.

Initially, disaster management was centralised but the process has been devolved to some extent with some county governments having also enacted laws and formulated policies and strategies that provides a framework for disaster management. The Ministry of Devolution and ASAL have created a generic model law on disaster management to aid county legislations with development of disaster management laws. Climate change mitigation and adaption strategies and disaster risk reduction have also been taken into consideration in County Integrated Development Plans.

So-called hard mitigatory measures, such as the planned construction of dams, must also be complemented by soft preparedness measures. Kenya is yet to enact the disaster management bill, which would see the creation of the National Disaster Risk Management Authority (NDRMA) charged with preparing and co-ordinating disaster risk management measures in the country. Figures within the NDOC have for years been calling for a framework to better coordinate disaster management activities.

With the disaster management activities being carried out by a number of agencies at different levels of government and within different ministries, there is likely to be overlap and delay in all phases of disaster management – especially response – with no clear roles and responsibilities or response mechanisms set out. It is unclear why the SOPs and emergency response plan that guides the work of the NDMU and NDOC and addresses the problem of roles and responsibilities were not followed. This was evident during this year’s flooding. A lack of preparedness forced the Makueni governor to establish disaster units in his county.

The Kilifi governor complained about the lack of support from the national government. In Tana River County, leaders also called for urgent support during the response effort. It is unclear why the government declined to allocate a Sh4.4 billion contingency fund to counties to manage disasters. When response to disasters is overwhelmed at the county level, the national government is supposed to intervene. The NDOC say the disaster management bill addresses response and funding issues.

If the bill is enacted, the NDRMA will, among other things, develop, update and coordinate implementation of national and county disaster preparedness, response and recovery plans.

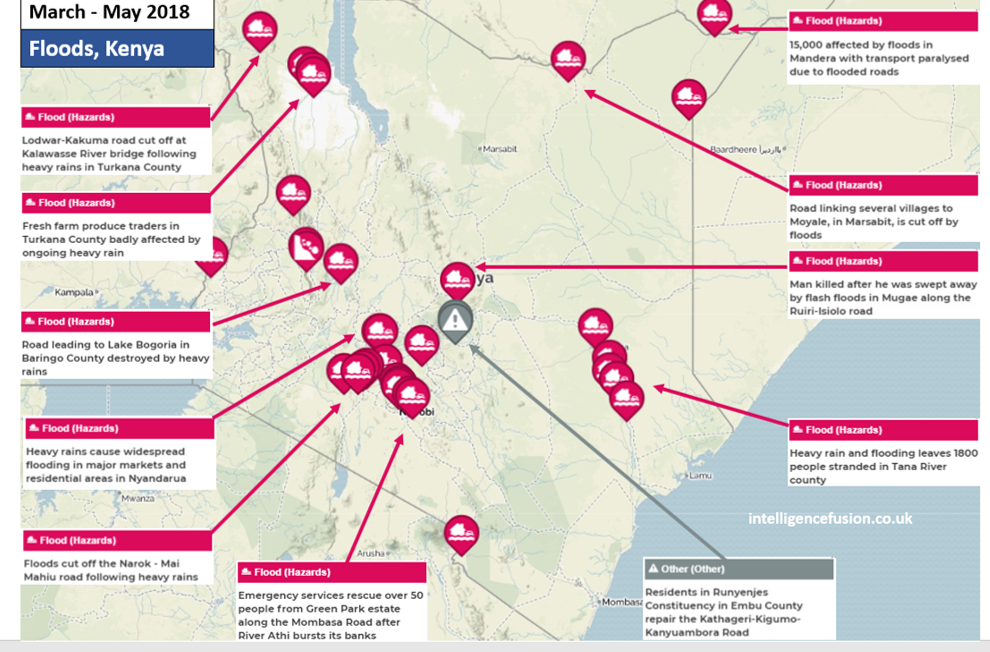

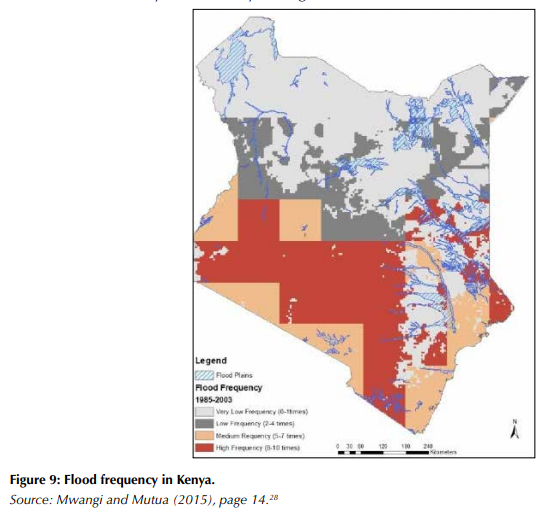

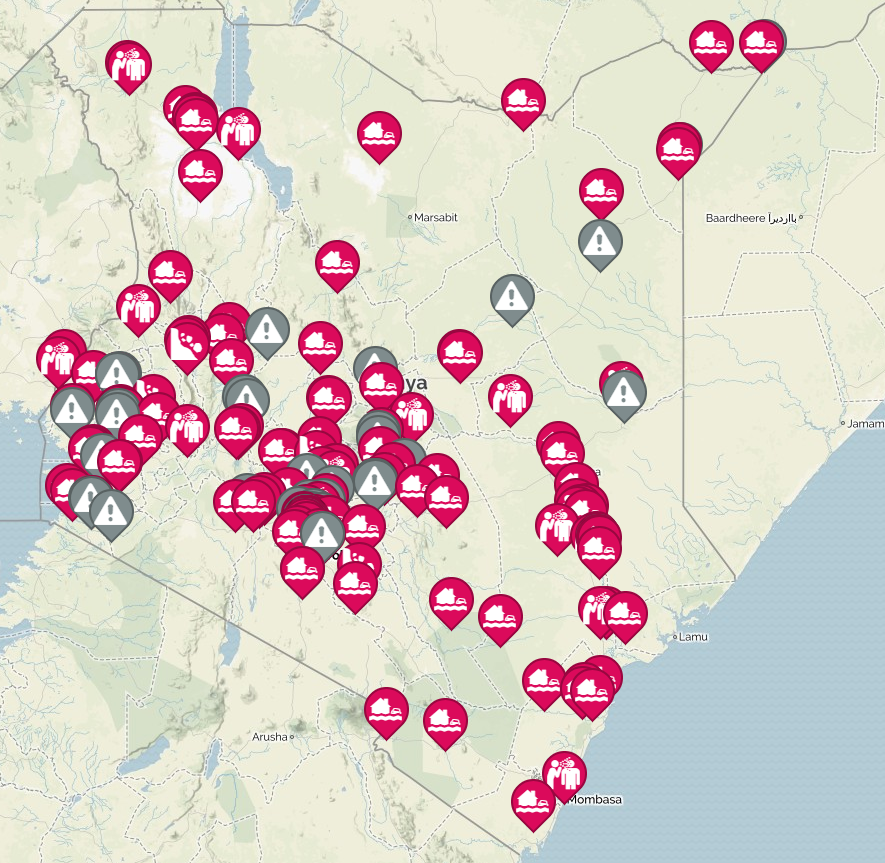

Intelligence Fusion has recorded approximately 176 flooding, landslides, diseases/illnesses and infrastructure-related incidents recorded since March 2018. Riverine flooding is the most common form of flooding across Kenya, and floods that have ravaged the country since March has shown this to be mostly true. Riparian and low-lying areas were heavily affected. Floods have destroyed crops, sections of roads (destroyed or flooded), houses, schools, bridges and other vital infrastructure.

Dams have also collapsed or overflowed, thereby exacerbating flooding. Inadequate storm drainage (in urban areas) and poorly constructed roads, bridges and dams have contributed to flooding or hampered response to it.

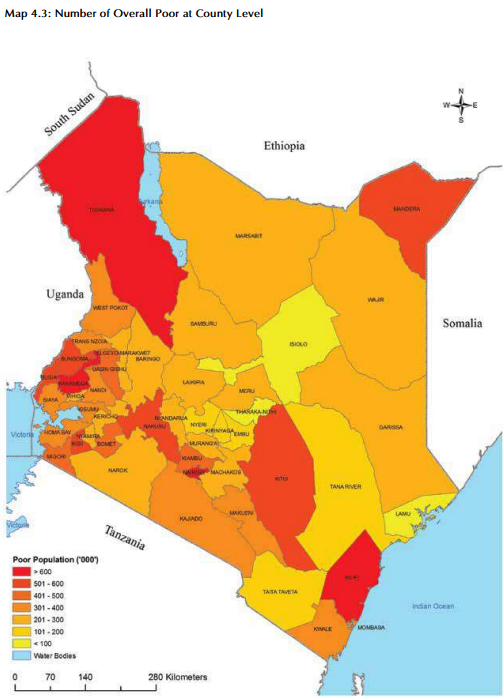

The floods that have affected much of Kenya since March has, according to the Kenyan Red Cross on 24th May, displaced 300,000 people and resulted in the deaths of 200 people in 22 counties. Tana River, Kisumu, Taita Taveta, Isiolo, Makueni, Turkana, Mandera, Garissa, Wajir, Kilifi, Kajiado, Homa Bay, Machakos, Narok, Kitui and Nairobi were the worst affected. About 16.4 million Kenyans live in poverty across the country with 3.2 million residing in rural areas suffering from extreme poverty. According to figures from 2015/16, the poorest four counties are Turkana (79.4 %), Mandera (77.6%), Samburu (75.8%) and Busia (69.3%). Turkana County alone accounts for close to 15 per cent of the extreme poor in Kenya. Overall, about 84 per cent of the total extreme poor (3.9 Million) are found in rural areas.

Tana River is the worst affected county. This year’s floods have been compared to those that occurred in 1997-1998 during the El Niño weather phenomenon. In April, approximately 150,000 people in the county were affected after the River Tana burst its banks. A further 6,000 were affected in Kilifi and 3,000 more in Lamu. Tana North Sub County and Tana Delta Sub-County were worst affected followed by Tana River Sub-County. Hundreds also contracted water-borne illnesses.

Crop farmers in the area lost all their farm produce and pastoralists lost more than 700 head of livestock. The county spent at least Sh100 million to purchase rescue motorboats and food and non-food relief items. The county has incurred losses of over Sh2 billion with at least seventy percent of the county flooded.

Kenya is to begin small-scale oil production this month from oil fields in Turkana. 3000 bpd of oil will be transported to Mombasa port by road until an oil pipeline is built from oil fields in Turkana to Lamu port. The incidents below show how floods affected or destroyed sections of roads around the country.