Islamic State on The Fringes of Central Asia: The Emergence of IS-KP in Northern Afghanistan

Islamic State first arrived in Afghanistan in January 2015 in the form of Islamic State – Khorosan Province (IS-KP) after IS declared the creation of a branch in the Khorosan Province region (historic term used to describe the area including Afghanistan.) After heavy fighting between the already dominant Taliban insurgency immediately after the announcement of IS-KP, the group was able to seize a relatively significant area of territory across the East and South of the already war weary country. The initial shock of IS-KP’s emergence may have taken the Taliban and the National Unity Government (NUG) alike by surprise, but the Taliban soon regained control of their lost districts, leaving IS-KP with just a handful of districts in Nangarhar Province. Since IS-KP’s formation, their time line has very much been characterised by being on the receiving end of US air power, most noticeably the MOAB (Massive Air Ordnance Blast) dropped on IS-KP positions in the Achin district.

The groups rise and seemingly sudden appearance may suggest an element of centralised control over IS-KP, and even close coordination with their counter-parts in Iraq and Syria. However, IS-KP was not under unified control in the beginning and their cooperation with IS in Iraq and Syria (here on referred to as ISIS) was unclear. Instead, IS-KP in its early stage was largely made up of Pakistani militants who had moved into the south eastern districts of Nangarhar Province such as the Achin, Deh Bala and Nazyan districts. The Pakistani militants, who mostly came from the Orakzai agency on the Pakistani side of the Afghan-Pakistan border were forced into Afghan territory after two large scale Pakistani operations forced them to retreat across the border. At first, the NUG felt that the influx of Pakistani fighters could be used as a counter-weight or a buffer to the Taliban but it slowly became apparent that such a policy would not be effective. The militants which had crossed the border into Afghanistan hailed from Pashtun tribes such as the Afridi tribe, and therefore, whilst foreign in one sense of the term, the militants were actually fairly closely connected to areas of Nangarhar through tribal connections.

Many of the new militants were from the heavily decentralised Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) but were soon joined by disgruntled members of the Afghan Taliban. Further recruitment was supported by IS-KP’s ‘Voice of the Caliphate’ radio station which broadcasts in Nangarhar (a popular medium in illiterate areas of Afghanistan.) Fighters from Lashkar-e Islam also formed a significant section of IS-KP’s ranks, allegedly not merging with the group but cooperating closely in Nangarhar’s Nazian district. The similarity of IS-KP’s flag and Lashkar-e Islam’s also caused many to see the two groups as identical leading to some confusing media reports. IS-KP also attempted to establish and maintain a new front in Helmand Province (Kajaki district) under the leadership of Abdul Rauf Lhadim, a former Guantanamo Bay detainee and ex-Taliban commander. Exactly how much cooperation there was between Lhadim’s fighters in Helmand and IS-KP’s fighters in Nangarhar is unclear, but believed to be minimal. Lhadim’s isolated IS-KP Helmand front soon evaporated under Taliban pressure, thus removing IS-KP influence in a Taliban stronghold. Lhadim’s short lived presence in the Kajaki district is often recorded as a period of IS control/influence in the area, in much the same way that one would map a conventional military offensive. However, Lhadim was not new to Helmand and had been operating in the area for quite some time under the Taliban. Lhadim’s IS-KP Kajaki episode reflects the way in which IS-KP grew organically from militants and commanders who were already in place, rather than a sudden appearance of foreign fighters. According to a study referenced by Casey G. Johnson, out of a sample of 52 mid-level commanders in mid-April 2015, 40 were former Taliban, 5 were Lashkar-e-Islam, 4 from Al Qaeda and 3 with no prior affiliation.[i] These figures show that IS-KP was not formed out of new militants imported into the region from Iraq and Syria (as many feared) but was instead the realignment of militants already residing in the AfPak region.

Before progressing to focus on the rise of IS-KP in the north of Afghanistan, it seems fitting to see the connection (or lack of) between physical geographical control of territory and lethality of attacks. The Taliban own substantially more territory than IS-KP, yet IS-KP continues to conduct highly lethal attacks in Kabul, and have claimed responsibility for many of the cities attacks throughout 2017. In explaining this apparent paradox, the Taliban’s ongoing attempt to avert Afghan civilian casualties in order to create an air of legitimacy goes some way to reduce the volume of civilian casualties caused by Taliban attacks. Therefore, Taliban attacks in the capital tend to specifically target foreigners as part of their anti-foreigner and anti-government rhetoric, limiting their lethality somewhat. IS-KP on the other hand, despite the vastly smaller amount of territorial control, is not restrained by such concerns. IS-KP’s attacks carry the hallmarks of those seen carried out by ISIS, in which maximum violence and high civilian casualties are intended to attract additional attention. The connection between IS-KP territorial control and volume of attacks in Kabul is only paradoxical when regarded as inter-related with the sheer volume of IS-KP attacks in the city. The conventional military capacity of IS-KP is fairly minimal relative to that of the Taliban, and therefore correlates with their limited geographical control relative to that of the Taliban. IS-KP does not need substantial geographical control to carry out attacks in Kabul, which are believed to be partly carried out by a cell of IS-KP militants recruited from a radicalised middle class of young educated militants from Kabul itself.

IS-KP’s Northern Stronghold: IS-KP in Jowzjan Province

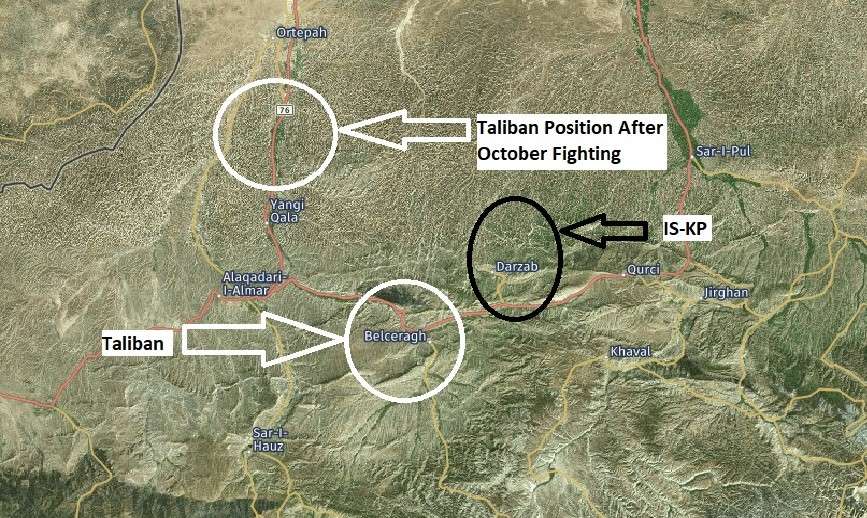

Whilst IS-KP added to the violence of the South and East of Afghanistan, IS-KP also managed to form an enclave in the countries relatively stable Jowzjan Province. In 2015, a Taliban commander, Qari Hekmat, defected from the Taliban and pledged allegiance to IS-KP, who in turn accepted his pledge of allegiance. In doing so, Hekmat took with him fighters loyal to him, (personal loyalties frequently carry more weight than broader idealogical allegiances) and swapped Taliban control of the Darzab district for IS-KP control. Soon after, Hekmat’s fighters launched an offensive in the neighbouring Qush Tepa district, forcing the Taliban out of a second northern district.

The Taliban were unwilling to allow IS-KP to establish a foothold and formed a counter attack in the same month, attempting to forces IS-KP out and regain lost ground. The Taliban did at first seize some villages from Hekmat’s fighters, but were soon forced to withdraw to the Astana area of the Dowlatabad district of neighbouring Faryab Province. Since the flare of violence, the battle lines have largely remained the same. The Taliban have since gained additional control in the Belceragh district close to the IS-KP controlled area at the end of November 2017, but no significant territorial gains have been made at IS-KP’s expense.

During this fighting, ANSF personnel played a largely insignificant role, not out of policy but out of a lack of manpower. Government control is limited to the district centres, and normally in the area in question there are approximately 50 ANP personnel supported by a smaller contingent of NDS personnel. With such small numbers, a substantial patrol ‘outside of the wire’ would leave the already precarious positions even more sparsely defended.

Rather than being a unified group controlled by centralised leadership, IS-KP has acted as more of banner for disgruntled militant commanders to fight under. With this said, there is still communication between the various groups but how much exists between IS-KP’s northern enclave and the rest of the groups fighters in the east is unclear. However, in June 2017 a delegation of IS-KP militants led by Sayed Jalal was arrested by Taliban militants on their way to the Darzab district.[ii] The delegation had been dispatched from IS-KP in Nangarhar Province, suggesting that there is some coordination between the groups.

Whilst connections between IS fighters in Afghanistan are weak, it is not clear if Hekmat has ever sworn allegiance to the Caliph or to a representative. Whether or not he has would also not necessarily change the tactical situation on the ground in Jowzjan either. The Darzab and Qush Tepa districts are remote and far removed, previously they were used as a safe haven for Taliban militants from security forces before Hekmat’s defection. Therefore, whilst Hekmat now controls a considerable amount of territory, he is also surrounded. The arrest of a five man IS-KP delegation travelling to Darzab highlights Hekmat’s geographical isolation and the difficulty in reaching him. Hekmat has in response to his isolation relied mostly on two forms of funding for their activities, neither of which are new to Afghanistan. Hekmat has funded his activities through collection of tax from locals in his area of control and poppy cultivation. Before 2016, poppy cultivation in Jowzjan Province was fairly minimal, however, according to statistics provided in an Afghan Analysts Network report, by 2016 98% of the poppy cultivation in Jowzjan Province was coming from the two IS-KP controlled districts.[iii] Hekmat’s funding from poppy may act as a driving factor behind clashes between Tajik or Turkmen border forces and Afghan drug smugglers which occur along the border. It would be a stretch to describe these fire fights as an ideologically driven move on behalf of IS-KP or the broader ISIS group to infiltrate Central Asia and Russia.

Foreigners Amongst IS-KP’s Northern Enclave

Unlike IS-KP’s Middle Eastern counterparts, foreign militants have not played such a high profile role in the group, but this is not to say that the group is free from foreign militants. Firstly, as already mentioned the eastern IS-KP forces were largely backed up by Pakistani fighters (albeit from similar tribal groups, rendering the term ‘foreign’ open to interpretation.) In the north, IS-KP’s ranks have been swelled by militants from Central Asian groups such as the Turkistan Islamic Party. Hekmat’s fighters have also received support from the fighters previously loyal to the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) who have featured in Afghanistan long before IS-KP and have clashed with the Taliban in the past.

In 2017, media reports caught the attention of the international community after a series of claims suggested that fighters from France were fighting for IS-KP in Afghanistan.[iv] Media reports supported by claims allegedly made by local security forces commanders in the area claimed that multiple foreign fighters from Europe, North Africa, Iraq and Syria were now fighting in Afghanistan after being squeezed out of their Middle Eastern territory. So far, little evidence has emerged to support these claims, and it seems that some ANSF commanders may have exaggerated figures. There have been some accounts of two French militants nicknamed ‘the engineers’ working in the Darzab/Qush Tepa area extracting minerals (although it is not clear exactly what they were extracting) but this does not signify waves of foreign militants. It is also difficult to comprehend how foreign militants can support IS-KP’s northern territories, as access to the area is incredibly limited. The borders of Afghanistan’s neighbours (Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) are heavily policed, making illegal border crossings difficult. On the 15th December 2017 for example, a French militant was arrested in Tajikistan whilst trying to join IS-KP in Afghanistan.[v] The would-be militant’s attempt to traverse Tajikistan’s heavily policed and close knit community of the border areas were mocked for naivety. Other isolated incidents of militants crossing borders in the area have been reported[vi] and are allegedly increasing in frequency but still remain relatively low level.

Threat of IS-KP to Central Asia

Central Asian states (CAS) have typically downplayed the threat that insurgent groups in Afghanistan pose towards their own national security and have allowed little information about the subject to be disseminated. Russia on the other hand has utilised the threat of Salafist and Wahhabist groups in Central Asia as catalyst for further engagement in the region. Russian fears of ISIS activity in Central Asia appear to have arrived in two distinct moments, the first in 2013 when a Turkmen militant was captured by Syrian security forces close to the Turkish Border and the second when Russian media began to speculate about an IS invasion of Central Asia in 2015[vii] (around the time Hekmat defected to IS-KP.) ISIS’s attack of Central Asia (which Russia believed would act as a corridor to Russian territory) never materialised, but represents a general fear in Russian media that religious extremism in Central Asia allows ISIS an entrance into the region.

Russia’s fears of a large scale invasion appear to be largely based upon myth and media driven paranoia. Media driven paranoia contributed to multiple accusations that groups such as the Sufi Gulen Movement in Turkmenistan may be actively recruiting extremists in the region.[viii] However, Turkmen militants fighting in Iraq and Syria are not formed into a national militia like many other foreign militants fighting in the Middle East are, suggesting a more ad-hoc recruitment policy of recruits from Turkmenistan and the broader region. Russia’s fears of imminent ISIS attack seem to be further disproved by the distinct lack of ISIS and IS-KP organised incursions into Central Asian territory, as the next paragraph will discuss.

With Qari Hekmat’s IS-KP fighters being the closest representation of ISIS to Central Asia, any ISIS or IS-KP attack into the region (however unlikely) would most likely involve Hekmat. However, upon analysing the motivation of Hekmat to join IS-KP from the Taliban, one can see that an invasion of Central Asia does not appear to be high on Hekmat’s list of priorities. Hekmat’s defection to IS-KP was based more upon a recent disagreement with the broader Taliban leadership, with a hint of opportunism, then it was an ideological shift. Furthermore, Qari Hekmat is not believed to have sworn an oath of allegiance to central ISIS authority in Iraq and Syria, and is less likely to as the group’s territory in the Middle East shrinks rapidly. To further criticise Russia’s paranoia of an Islamic State invasion, the remoteness of IS-KP’s position in Northern Afghanistan would also make any large scale infiltration of Central Asia a logistical nightmare.

Russian media’s fear of an attack from ISIS in Central Asia seems to be the result of a somewhat binary viewpoint regarding the international movement that is the Islamic State. The fears are largely based upon the assumption that ISIS is a unified global organisation which exists much like a modern state, in which decision making and activity is all channelled through a single bureaucracy. In reality this is not the case, as shown in this article, even IS-KP in Afghanistan is not fully unified, let alone working in congress with their Middle Eastern counterparts. With this said, countering the threat of ISIS in Central Asia has involved into a significant aspect of Russian regional policy. However, it is doubtful that Russian strategy is based solely upon a belief in media paranoia. Instead, Russia appears to see the threat of the Islamic State in Afghanistan, and therefore potentially Central Asia, as a vessel on which Russian influence can be transported into the region under a veil of legitimacy.

Summary

Contrary to predictions, IS-KP has managed to survive in Afghanistan after losing much of its territory to the Taliban in 2015. Geographically and as a result of Taliban and belated NUG counter-attacks, IS-KP-s control in Afghanistan is minimal compared to that of the Taliban. However, this is not to say that the group is not a threat to the security landscape of Afghanistan. The groups base in the Spin Ghar Mountain Range in Nangarhar Province has allowed them to develop into an entrenched insurgency, despite constant US air strikes and special forces raids. Qari Hekmat’s northern enclave also proved its resilience when it protected its small foothold from Taliban attacks, despite the Taliban drawing fighters from across the country to destroy Hekmat.

However, it is also important not to exaggerate the threat posed by IS-KP to Central Asia and Russia in the way that state-backed Russian media has. The threat of ISIS to Central Asia from home grown militants or militants returning from fighting in Syrian and Iraq does present a threat, is not the same as the threat posed by IS-KP in the north of Afghanistan. The isolated IS-KP position in Jowzjan Province, on the border with Central Asia, does not necessarily represent a bastion of central ISIS command, or a launch plate for further attacks into Central Asia. Instead, the northern IS-KP enclave should be regarded within the context of Afghanistan itself, rather than the global ISIS phenomenon. When viewed within an Afghan security context, Hekmat’s distant links with IS-KP in Nangarhar Province, and even more distant links with ISIS do not suggest that the group is planning to, or is able to launch a large scale campaign of infiltration into Central Asia from North Afghanistan.

[i]https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR395-The-Rise-and-Stall-of-the-Islamic-State-in-Afghanistan.pdf

[ii]http://www.firstpost.com/world/taliban-arrests-five-islamic-state-fighters-in-afghanistans-jawzjan-province-3657753.html

[iii]https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/qari-hekmats-island-a-daesh-enclave-in-jawzjan/

[iv]https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/french-fighters-appear-with-islamic-state-in-afghanistan/articleshow/62006304.cms

[v]https://www.novastan.org/fr/tadjikistan/tadjikistan-un-francais-condamne-pour-avoir-voulu-rejoindre-letat-islamique/

[vi]https://rus.azathabar.com/a/suspected-isis-fighters-captured-in-turkmenistan/28643048.html

[vii]https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/615221/Islamic-State-ISIS-jihadis-invasion-central-Asia-Russia-Moscow-Putin

[viii]http://centralasiaprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Turkmenistan-1.pdf