Hybrid Warfare and Escalation in the Baltic Region: A Security Overview

NB: A range of open source threat assessments served to inform this analysis. In addition, consultations were conducted with independent analysts, members of three NATO armed forces, and governmental actors in the Baltic Region. While the information is unclassified, these particular sources shall not be disclosed.

Russiaâs ongoing military operations in Southern Syria and Eastern Ukraine have prompted a re-evaluation of the security situation along NATOâs Eastern periphery. The Baltic Region, which is home to 85 million people (10% of all Europeans) and which processes 15% of global maritime trade, is increasingly targeted with often-subtle Russian encroachment. The so-called âclash of civilisationsâ here is nothing new, and both NATO and Russia have invested billions in one way or another to expand their sphere of influence (since 1993, Russia has allocated up to $6bn USD for consolidating national interests in former satellite states). The difference is, Russia appears to possess both the capabilities and intentions of using invasive force.

It is important to find the middle ground between, on the one hand, an exaggeration of âthe Russian threatâ (which might lead to improper resource allocation, brinksmanship, and political fatigue) and, on the other hand, dismissing the problem altogether. During his speech in Warsaw this July, President Trump alluded to an existential crisis in the West, and to the possibility of the destruction of our civilisation. On the other hand, former London mayor Ken Livingstone has rejected the existence of a Russian threat entirely. The reality is distinct from either of those.

Fundamentally, the NATO alliance faces a resurgent Russia that seeks to reduce the political and strategic influence of the Western bloc. Still wounded from the end of the last century and headed by a small group of hard-line nationalists, Russia is attempting a nationwide industrial transition back into the role of a global power, and has invested vast amounts of culture and capital in restoring a Russo-sphere in the developing post-Soviet states.

Below is an overview of the ongoing military and non-military frictions in the Baltic Region, some potential near-future scenarios, and their policy implications for the NATO member states. While the issues of âhybrid warfareâ are at present the most urgent, the conventional military situation is also required to show the bigger picture.

Hard Power Escalation

The hard power dimension to the NATO-Russia rivalry takes three forms: nuclear arsenals, conventional forces, and missile defence. In terms of nuclear capacity, Russia possesses the worldâs largest stockpile: 7,000 warheads. In comparison, three nuclear-armed states are members of NATO, in total possessing around 7,300 warheads, albeit in a non-integrated stockpile. There is speculation as to whether Russia would be willing to deploy nuclear forces at a tactical level (on the battlefield as opposed to striking enemy capitals or long-distance assets), however, until such time as the situation escalates to territorial acquisition, the notion remains distant.

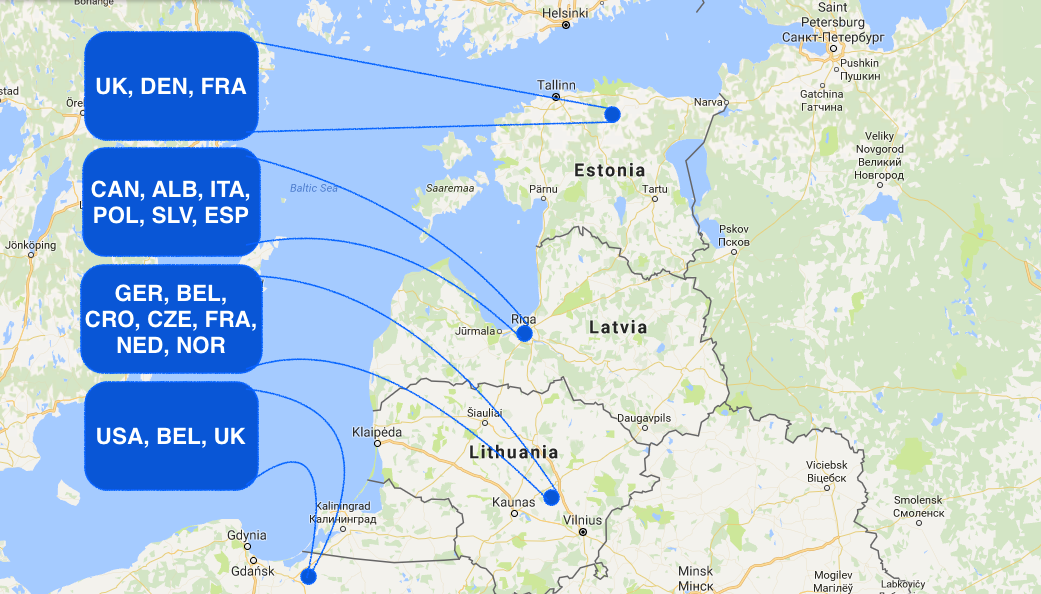

The second hard power comparison can be made in terms of military presence within the Baltic Region, and is far more tangible. Currently, Russia is capable of deploying 27 battalion battle groups across borders at short notice. A task force this size would be capable of overwhelming the NATO presence in a matter of days. The NATO deployment, known as âenhanced forward presenceâ (eFP) comprises of 7,200 troops across Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. The situation is more complex than a numerical contrast, however, firstly because the capabilities and experience levels of the two armed forces are asymmetrical, and secondly because the NATO presence in Eastern Europe is explicitly one of deterrence, rather than defence.

Regarding capabilities, the majority of NATO forces are better equipped and more agile, although Russia is in the process of a massive national rearmament and modernisation programme. Catalysed by a pyrrhic victory in Georgia, the reforms began in 2008 under Defence Minister Anatoliy Serdjukov. At present, they are estimated to be approximately 50% complete, and 17 trillion rubles ($300bn USD) have been designated to achieve completion by 2025. While the current regime of economic sanctions against the country are taking their toll (the development of the Russian equivalent of GPS, known as GLONASS, has certainly been slowed), the system as a whole can sustain it. New missile technology is already being deployed in operations in Southern Syria, which has become an exhibition space for the Russian air force. In terms of ground forces, modernised T72-B3 tanks, BTR-82A personnel carriers, and unmanned aerial vehicles became field ready in 2016.

Source: armyrecognition.com

Source: military-today.com

Among the significant problems facing NATO as it prepares for a potential transition from deterrence to defence are interoperability and experience. One obvious obstacle to a fluid command and control structure is linguistics, but there are others. The organisation consists of 29 member states, all of which possess their own domestic security priorities, and most of which have spent the last fifteen years conducting mostly counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations. Despite large-scale exercises having been performed in anticipation of an equally capable conventional adversary, a contrast is unavoidable between, for instance, French troops adapted to the urban patrols of Opération Sentinelle, and Russian counterparts fresh from direct combat in Eastern Ukraine.

Figure 1: NATOâs Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in the Baltic States.

The third aspect to the hard power friction in the Baltic Region is just as crucial: the ballistic missile defence systems (BMD). These sites, spread across the region by both sides, are capable of detecting and terminating overhead missiles, but at present fill a crucial role in NATOâs deterrence infrastructure.

For Russia, long-range BMD systems include the S-400s placed in St Petersburg, Dmitrov Oblast, Semerovorsk (the far north), and Kaliningrad. Shorter-range systems have been placed in Kursk, Crimea, and Voronezh. Their short-range equivalent systems in NATO include the Patriot systems in Denmark, Germany, France and the Netherlands, and NATOâs long-range capabilities come from mobile sea-based Aegis systems in the North and Baltic Seas. Altogether, these systems form frontiers of Anti-Access Area Denial (known as A2-AD), which, when visualised, have come to a stalemate across the Baltic region.

Figure 2: BMD sites of Russia (red) and NATO (blue).

Hypothetical Offensive Scenarios

With these comparisons in mind, a conventional offensive operation from Russia could take a number of forms, all of which are highly unlikely at present, but possible in the next five to ten years. Unhindered by democratic processes and bolstered by domestic popularity, Russia maintains an extremely high readiness posture (at great expense) and has demonstrated the capability of conducting a limited land war.

The three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are militarily problematic for NATO. The geography of the region is unfavourable to its defenders, and all three countries have low population densities. An aggressive task force the size of Russiaâs could potentially reach Riga (the most vulnerable of the three capitals) within between 30 and 60 hours, probably in winter. Klaipeda is the only ice-free port in the Baltic States, making a blockade of the target territories relatively straightforward, and the SuwaÅki corridor in Poland would be the only convenient path of counter-supply.

Another point of strategic value is the island of Gotland, an established base on which would provide additional missile reach, and which is administered by Sweden, a non-member of NATO. Additionally, establishing a land bridge between Kaliningrad and Belarus would be of high priority for Russian forces.

While NATOâs collective defence agreement under the Treatyâs Article 5 does not require consensus, a substantial counter-strike involving imported forces may take a week or more, and would risk allowing Russia to consolidate territory. Land already taken could then be used in bargaining or to warn for further escalation in pursuit of geopolitical goals.

A scenario in which a Baltic capital is occupied by overt Russian forces is unlikely in the extreme, particularly while Russia is in the midst of rearmament. Any direct action would almost certainly be conducted with prior softening by sponsored political opposition, proxy elites, and agents in the target territory. However, there are many other instruments of coercion that Russia can and already does employ in the Baltic Region, and which constitute the more holistic strategic reality of âhybrid warfareâ.

Hybrid Warfare

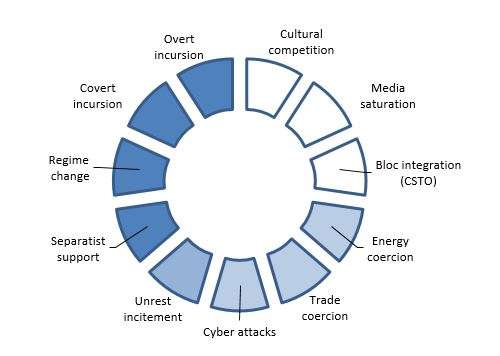

In an effort to roll back Western encroachment into the former Russian sphere of influence, the current generation of siloviki (former military and intelligence staff now occupying influential offices in Russian government) incorporates many aspects of soft power into its broader military efforts. So-called âhybrid warfareâ is not a new phenomenon, but the actors involved are equipped with dynamic and sophisticated tools with which to conduct it that were not available in the Cold War. Russiaâs âGerasimov doctrineâ of 2013 prescribes a 4:1 ratio of non-conventional to conventional force; in other words, the phases illustrated in Figure 3 that fall short of violent force are now the major focus of operations.

Figure 3: The hybrid warfare spectrum.

Each phase is incrementally more intrusive than the last, and all but the final phase revolve around the Kremlinâs plausible deniability. Together they reflect the reality that, in an international community that is ostensibly bound by law and averse to official war declaration, nation states can capably interfere abroad without the âtraditionalâ and distinguishable crossing of lines. Cultural competition, media saturation, energy coercion and cyber attacks are already manifesting themselves in the Baltic States, with attempted electronic interference (jamming, smearing, intelligence theft) occurring thousands of times per day.

In Lithuania, for example, Russian disinformation campaigns target and smear the countryâs history, NATO and EU exploitation, high members of government, and the treatment of ethnic minorities. Such tactics aim to degrade public trust in the Western institutions, and will be most effective in the Russian-speaking communities that utilise Russian media sources (this demographic constitutes fully one quarter of the populations of Estonia and Latvia). Due to the far higher regulation of domestic media in Russia, media tactics are essentially a one-way conduit.

Policy Implications

The situationâs policy implications for the Baltic States and NATO at large are far reaching. In the short-term, there are a number of mitigating measures that could be taken, beginning with a reinforcement of collective political will. While the larger states of Western Europe may be inclined to dismiss any nefarious activity a thousand miles away, it should be acknowledged that even a partially successful hybrid intervention into the Baltic States would undermine the legitimacy and reliability of the NATO bloc, opening the gates for further diplomatic, economic, and military encroachment.

When Western governments are knowledgeable of the broad range of capabilities associated with this dynamic threat (including the use of agents, imported paramilitaries, deception, intimidation, and bribery; infiltration of political groups and government services; and persistent denial) they can fortify vulnerable sectors of society. These include the media, religious organizations, political parties, and government agencies, particularly those with high engagement with Russian minorities. Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities in the Baltic border districts would also contribute to the overall deterrence efforts, especially in Eastern Latvia.

In the long-term, Russiaâs subtle expansionism has complicated the United Statesâ political pivot to the Pacific. The US remains by far the largest contributor to European collective defence and deterrence, and constitutes the most important asset to Baltic sovereignty. Therefore, proposed measures to centralise security within Europe – for example with the establishment of an EU armed force – might only prove divisive within NATO and subtract from American commitment.

While much of modern Russian activity is attributed directly to the figurehead of Vladimir Putin, it should be noted that any substantial shift in policy in the event of his eventual departure is unlikely. Even without him, the country is capable of continuing as normal due to its cartelised upper government. Moreover, Russiaâs reliance on its natural resources for diplomatic leverage may not be as short-lived as European decision-makers have hoped. While it does derive extensive purchase from the fossil fuel markets, it has simultaneously grown to be one of the worldâs leading investors in green energy. This is likely to prevent a decline in influence parallel to the gradual global diminishing of non-renewables.

Conclusions

Putin and his surrounding ideologues understand Russia as a rising superpower that has been denied its rightful place by an aggressive transatlantic regime. The countryâs foreign policy objectives in the former Soviet sphere include the division and degradation of European institutions, and the maintenance of political leverage across Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Russian policymakers know that the threat NATO poses to Russian territory is zero, but West does hamper the spread of political influence and assets.

In response to military build-ups in the Baltic Region and a decade of escalating Russian military interventions abroad, NATO seeks to maintain a deterrent presence in the Baltic region through troop deployment and BMD sites. Adequately defending the region from attack would require turning the Baltics into a de facto army camp, but as a deterrent, current numbers are nearly adequate.

Low-level, nonviolent subversion is currently happening in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and could quickly intensify in the future. Covert violent action of the sort seen in Crimea is unlikely but possible, and committing to a counter-strike could prove divisive for NATO. The question of overt confrontation is one of counter-mobilization: Russia could easily take territory in the short-term, but a response, while slow, would benefit from NATO ground dominance. Far more pressing at the moment is the issue of hybrid warfare.

While the 2020 development goals will not be reached, Russia retains capability of conducting one limited war. Although Russiaâs conventional military power is nowhere near that of NATO, international reactions to the display of its rejuvenated armed forces have boosted its prestige to an extent that far exceeds actual material capabilities. Large, offensive military exercises such as ZAPAD 2017 (scheduled to involve 13,000 troops between the 14th-20th September) will be useful in indicating capabilities and intentions for 2018 onwards.