Democratic Republic of Congo: The Worst Case

The Democratic Republic of Congo is a misnomer. It has never had a peaceful transfer of power in its sixty-year independent history. Judging by the present behaviour of President Joseph Kabila, this may not change for the foreseeable future. Kabilaâs behaviour has become more authoritarian over the last few years. Opposition is weak and divided, despite Kabilaâs blatant antidemocratic activities. The UN presence is shrinking, following the murder of two UN investigators and their translator. The east of the country remains in a state of low-level insurgency. The Catholic Church in the Congo is losing faith in its ability to keep the peace. While the DRC has been remarkable in its ability to survive, unless Kabila steps down, its future is bleak.

Bad history

The DRC achieved independence from Belgium in 1960, led by socialist nationalist Patrice Lumumba. Lumumba was violently and quickly ousted in murky circumstances by Joseph-Desire Mobutu, his chief of staff of the Congolese Army. Mobutu ruined the country so thoroughly no one within the country could marshal the resources to oust him. Therefore Mobutu was removed by forces from without.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-26875506

Hundreds of thousands of Hutus, fleeing the fallout of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, crossed the Rwandan-Zairean border. By 1996 Hutu guerrillas were counter-attacking into Rwandan territory, compelling the Rwandan government to invade. Instead of risking diplomatic blowback by an overt attack, the Rwandans backed a minor left-wing commander, Laurent Kabila, who had been battling government forces for years. Kabila provided a Congolese veneer until the invasion was a fait accompli. The weakness of the Zairean state allowed Kabila, with the support of Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and Angola to quickly oust Mobutu, who died in Moroccan exile.

Laurent Kabila quickly alienated his foreign backers lest he be seen as a foreign stooge. This led to Rwanda and Burundi turning on him, triggering the second Congo War in 1998. For a second time Kabila was dependent on foreign powers, receiving support from Angola and Zimbabwe against rebels and foreign troops. He was assassinated by his bodyguards in early 2001 and succeeded by his son, Joseph, the current president. The war dragged on until a ceasefire in 2003, but the dozens of armed groups with various grievances did not dissolve, and stability has remained elusive

For the last ten years the DRC has soldiered on, with a fragile state, a corrupt ruling class, an ongoing insurgency and the kleptocratic and nepotistic Joseph Kabila in power. However, 2017 may be the year Congo stops experiencing political stagnation and starts experiencing political violence and instability on a country-wide scale.

2017 may be the year Congo stops experiencing political stagnation and starts experiencing political violence and instability on a country-wide scale.

Joseph Kabila was appointed in 2001. He won an election in 2006, though his opponents complained of irregularities in the process and there was extensive violence in the country during and after the voting period. Under Kabilaâs aegis the Congolese economy has grown, though it could hardly have worsened after two wars and Mobutuâs depredations. Constitutionally, his 16-year reign should have ended with Kabila presiding over the first peaceful transfer of power in the DRCâs history, and setting a fine example to some of his neighbours. Instead, Kabila seems to be digging in. His recalcitrance, the weakness of the opposition, the instability of the DRC, lack of international focus and the mineral wealth of the Congo all risk combining into a perfect storm of political violence which could set the country back by years and kill thousands.

âDemocraticâ âRepublicâ of Congo

Joseph Kabilaâs term is up. He should have stepped down on 19 December 2016. He did not. Instead, he flooded the streets with his security forces, detaining dozens. Several people were killed. He argues that an election has not taken place because the countryâs electoral rolls are not complete, and that elections are too expensive. Therefore there is no successor, and therefore it would be a dereliction of duty to step down, leaving the DRC without a leader. This is Kabilaâs strategy: glissement, or âslippageâ. He seeks to defeat the opposition by a thousand boring and apparently legal cuts, interspersed with extreme violence.

Following his refusal to step down, a deal, brokered by the Congolese Catholic Church, was struck, ostensibly establishing a national unity government comprising opposition and Kabila administration politicians. Glissement struck again, buying Kabila four more months. By 28 March 2017 the bishops had withdrawn from the agreement due to a lack of good will amongst all parties. By withdrawing they hoped to bring the national impasse to international attention.

On Friday 7 April, Kabila chose Bruno Tshibala to be his prime minister. Tshibala is a former member of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress party, which is still actively opposing Kabila. No date has been set for elections.

Divide and conquer

A strong opposition is vital in the DRC, capable of uniting those with legitimate grievances against Kabilaâs administration to ensure he obeys the constitution and then providing a successor to the Kabila dynasty. Unfortunately, such an opposition is missing.

Moise Katumbi has fared well in polls, beating Kabila handily. However, Katumbi is in self-imposed exile in Belgium. The DRC is too dangerous for him. He has been accused of hiring mercenaries to stage a coup, and more prosaically trying to sell a house which was not his. The same charge has been levelled against Jean-Claude Muyambo, another politician, probably not coincidentally by the same accuser.

Etienne Tshisekedi was the elder statesman of Congolese opposition, and in much of the press coverage of the violence in September and December 2016 was often named as the person to steer the country to peace. Unfortunately, the octogenarian died in February 2017. His son Felix might be the man to finish his fatherâs work, but a lack of experience (he has spent most of his life in Belgium) and undeclared presidential ambitions might affect the shaky coalition opposing Kabila, which includes Moise Katumbi, another presidential hopeful. This would shatter the coalition and divide Kabilaâs opponents more than they already are. Again, we see glissement at work: if Kabila was forcing through constitutional amendments to extend his power, it would unite the opposition. By doing nothing, he has given them the space and time to fall apart. The appointment of Bruno Tshibala will further divide them, showing Kabila can empower those willing to work with rather than against him.

This is not to say Kabilaâs rule is peaceful: during protests in September opposition buildings were torched. Furthermore, disloyal radio stations have been shut down and internet communications are being monitored.

Protests scheduled for Monday 10 April failed, presumably due to a lack of credible opposition worth demonstrating for and reasonable concerns that any further protests will end in bloodshed.

A missing opposition, divided, dead or scared, is bad for the DRC. United, the opposition can pressure Kabila to step down peacefully, or step into a power vacuum should the Kabila administration collapse. Fragile Congo might not survive an interregnum.

Fragile, rich, violent

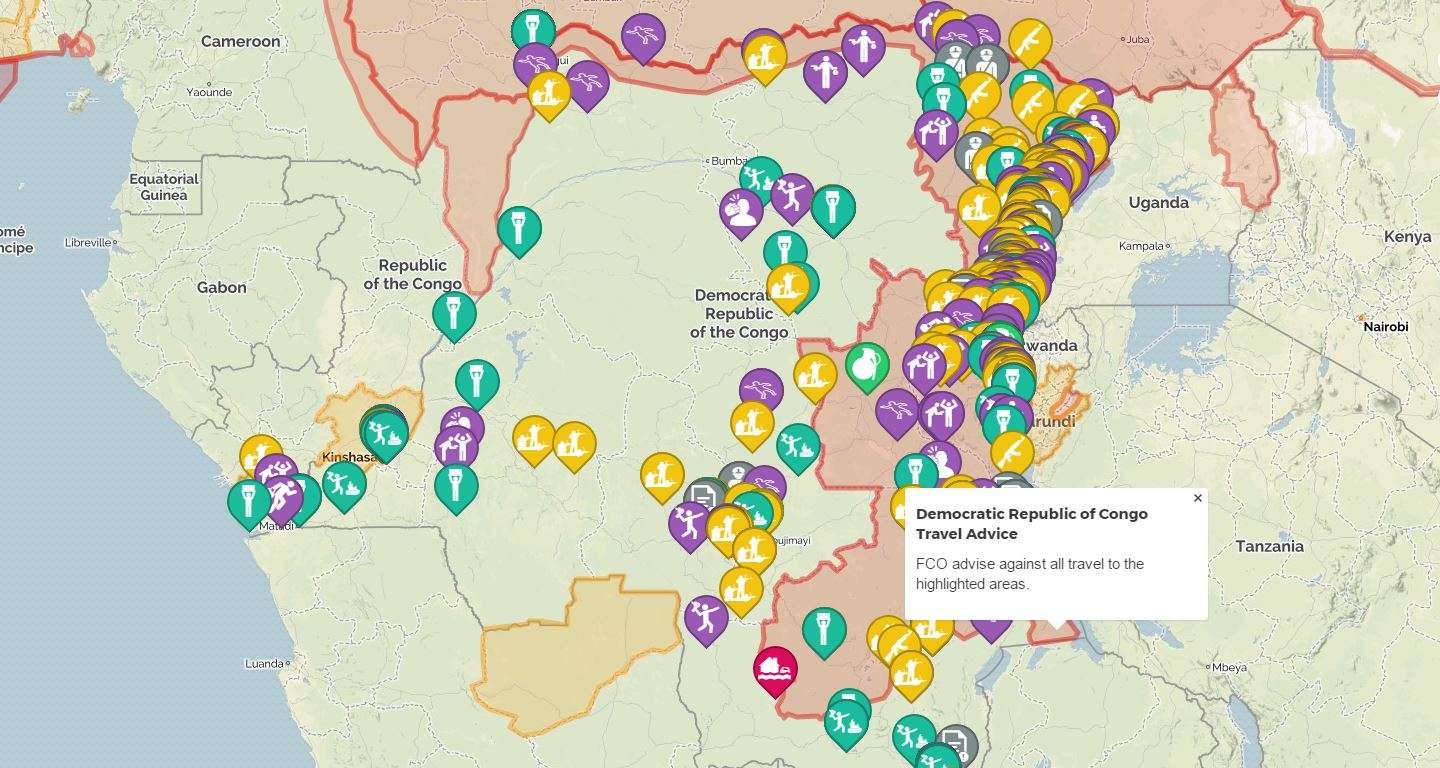

Another reason to worry about Congoâs future can be found in the east of the country. As discussed above, the east has been a theatre of conflict for decades, hosting many armed groups with no affection for the state. The current threat in the east now is called M23. The organisation has been fighting the Congolese armed forces for years. They are also the main reason for the continuation of the UN mission, MONUSCO, in the region.

Eastern Congo is also extremely mineral-rich, which has allowed rebel movements to sustain themselves via smuggling, as well as providing an incentive for external meddling: Rwanda claims to have stopped sponsoring rebels in the east, but not before many Rwandans made their fortunes in illegally smuggled tin, tantalum and tungsten. The area has been in the news recently because of the discovery of the bodies of two UN members and their interpreter, as well as mass graves and leaking footage of apparent war crimes being perpetrated by the Congolese army.

https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Minerals+and+Forests+of+the+DRC1.jpg

Eastern Congo is an ulcer draining the strength of the country. MONUSCO has recently been reduced in size, despite the scale of its responsibilities (notably M23 captured the city of Goma in 2012. The Congolese army fled without firing a shot). Congoâs army is utterly unfit, weakened so thoroughly by neglect that it may be a deliberate strategy on Kabilaâs part: soldiers owed back pay may avoid deserting to get their full due, and a poorly supplied and armed force is less of a threat to anyone, including the president who ostensibly commands them.

What impact could the bleeding east have on this yearâs political drama? Firstly, Mobutu and Kabilaâs father were both defeated by rebellions coming from the east, and though MONUSCO and a lack of foreign patronage makes this less likely it is still possible. Urban instability and political chaos could leave large parts of the country ungoverned, giving armed opposition groups a free hand, as soldiers realise their pay is never arriving. This would be amplified by the loss of the resource wealth with which Kabila pays his security forces. It is this same wealth which would need to be used to rebuild the country in the future, so its loss would be calamitous. Finally, a deterioration could give Kabila the opportunity to cling to power, arguing he cannot step down with Congolese citizens are in danger. Like Mobutu, Kabila could end up isolated in Kinshasa, too strong to be removed but too weak to control the rest of his country.

Out of Africa

Outside the Congo there is little anyone is willing to do to ensure a peaceful transfer of power. MONUSCO is theoretically negotiating Kabilaâs exit, but he has shown little interest. Reduced in size, the mission is maintaining a facsimile of peace in the east, but lacks the power to compel Kabila to do anything he does not want to. And despite the success of the British mission in Sierra Leone, the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq and the intervention in Libya has left the international order understandably reluctant to become deeply involved in the Congo, a country the size of Europe with only 2,000 kilometers of road (for comparison, the small British Isle of Wight has about 800).

When the leader of Gambia, Yahya Jammeh, refused to step down following his electoral defeat, tanks from ECOWAS, a coalition of African states, entered the country. Unsurprisingly, it was only then that Jammeh decided to respect the ballot box rather than the bullet. Given the DRCâs recent history, during which it was invaded by at least half a dozen neighbours, could we expect a similar outcome? This is unlikely. Angola has called for Kabila to exit, after backing Kabilaâs father during the second war. Congo is much larger than tiny Gambia, and central Africa lacks an organisation comparable to ECOWAS. Of the nine countries Congo abuts, four have leaders who have been in power nineteen years of longer. None of them are likely to go to war for democracyâs sake. On the other hand, Mobutu earned enemies because the failed state over which he presided harboured rebel groups which harassed his neighbours. If the DRC becomes destabilised by a recalcitrant Kabila, refugees and rebels could pose enough of a problem for neighbouring leaders to act.

Worst case scenario

Hopefully Kabila will do the right thing and peacefully leave the presidential palace, showing himself to be a patriot rather than a despot. However, he has not given any indication of wanting to do this, preferring to cling to his power and the vast kleptocracy he has built for himself and his family over the years.

Perhaps the best scenario we can hope for is a peaceful authoritarian Congo in which Kabila rules unopposed despite the odd election, comparable to Zimbabwe. The odd rally might end in bloodshed and parts of the country, starved of government attention, might become gangrenous and wither away from Kabilaâs control. The east would continue to suppurate but between MONUSCO and the wizened Congolese army it could be contained. The DRC would soldier on.

The worst case scenario would be political instability and civil violence. There are still lots of guns in the country, and men who have fought before. There is also a lot to fight for, especially if fighting is the only way to affect change. Kabilaââs praetorian guard of police and security services are better paid, armed and trained than the army and could put up stiff resistance as long as Kabila can pay them, so he would be unlikely to go quietly. After all, the Kabila dynasty survived one war intended to oust him. The Second Congo War is perhaps the third bloodiest war in human history. An estimated five million people died due to disease and malnutrition in conditions caused by the war. This is the worst of the worst case scenario: when the state in Congo fails, civilians die in droves, neglected to death by those competing to govern.

The future of the DRC is in Congolese hands. It is up to Kabila to do the right thing. It is up to the opposition to put aside personal ambitions, or to admit them openly to prevent Kabila taking advantage of them. And it is up to the Congolese people to brave political repression and to put an end to glissement.

http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21712132-constitution-says-joseph-kabila-no-longer-president-he-begs

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2011/jan/17/patrice-lumumba-50th-anniversary-assassination

https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/05/09/what-mobutu-did-right/

http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21579462-almost-unnoticed-un-about-fight-its-first-war-gamble-worth-taking-art

http://www.enoughproject.org/blogs/congo-first-and-second-wars-1996-2003

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/feb/11/theobserver

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2016-12-15/with-his-family-fortune-at-stake-congo-president-kabila-digs-in

http://africanarguments.org/2016/12/21/congos-political-crisis-after-19-december/

http://intellfusion.ambix.io/#incident/31d20d7f-e740-462b-87fa-3b44db1b23a3

https://trello.com/c/lIQukILn/136-http-time-com-4604626-congo-kabila-protests-glissement-katumbi

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/03/world/africa/congo-joseph-kabila-elections.html?action=click&contentCollection=Africa&module=RelatedCoverage®ion=Marginalia&pgtype=article&_r=0

http://www.catholicherald.co.uk/news/2017/03/28/bishops-in-democratic-republic-of-congo-withdraw-from-peace-talks/

http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-congo-politics-idUKKBN1792Y4

http://congoresearchgroup.org/new-crgberci-report-nationwide-political-opinion-poll/

http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21701397-president-joseph-kabila-playing-it-nasty-congos-president-jails-his-rival

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/10/democratic-republic-of-the-congo-faces-civil-war-if-president-fails-to-quit

https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/04/04/the-man-who-would-be-king-of-democratic-republic-of-congo-felix-tshisekedi/?utm_content=bufferb5e7a&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/sep/19/democratic-republic-congo-demonstrations-banned-police-killed-joseph-kabila-etienne-tshisekedi

http://intellfusion.ambix.io/#incident/8ef07373-756d-4880-8af1-e9e9f359f1fc

http://time.com/4604626/congo-kabila-protests-glissement-katumbi/

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-congo-politics-idUSKBN17C1NC

http://www.economist.com/news/international/21699136-long-and-costly-operation-can-do-little-bring-peacebut-cannot-end-either-never-ending

http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21579462-almost-unnoticed-un-about-fight-its-first-war-gamble-worth-taking-art

http://uk.reuters.com/article/us-congo-democratic-rwanda-minerals-idUSBRE89F1M320121016

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/03/bodies-suspected-workers-drc-170328151604155.html and https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/17/world/africa/democratic-republic-congo-massacre-video-.html?_r=0

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-congo-violence-idUSKBN16R0D4

http://www.economist.com/news/international/21699136-long-and-costly-operation-can-do-little-bring-peacebut-cannot-end-either-never-ending

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/03/renews-smaller-drc-peacekeeping-force-170331184227995.html

http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21701397-president-joseph-kabila-playing-it-nasty-congos-president-jails-his-rival

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/03/renews-smaller-drc-peacekeeping-force-170331184227995.html

http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21579462-almost-unnoticed-un-about-fight-its-first-war-gamble-worth-taking-art

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/01/jammeh-arrives-banjul-airport-stepping-170121210246506.html

http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21712132-constitution-says-joseph-kabila-no-longer-president-he-begs

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/16/sunday-review/congos-never-ending-war.html

Report written by Brendan Clifford