Analysis: Carillion Compulsory Liquidation

by Louise Hogan

On Monday morning, January 15th 2018, after emergency talks with creditors facilitated by the UK government failed, it was announced that UK construction giant Carillion would enter compulsory liquidation. The Wolverhampton based company was unable to survive a massive £1.5 billion worth of debt, including a £580 million deficit in its 28,000 member strong pension scheme.

Carillion’s collapse has huge economic and political consequences. Not only does Carillion employ some 20,000 people in the UK and another 23,000 globally, it is one of the UK’s largest service providers with an array of contracts across the education, health, transport and defence sectors. The knock on effects of Carillion’s collapse are wide ranging, casting doubt on future infrastructure projects such as the HS2 Raillink, putting thousands of jobs and pensions at risk and threatening the future of some 30,000 small businesses who worked with the company. Other large construction companies will also take a hit due to Carillion’s tendency to engage in consortium projects; Carillion’s partners on the £550m Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route contract for instance will have to make up Carillion’s £60-80 million share.

Carillion’s Fall From Grace

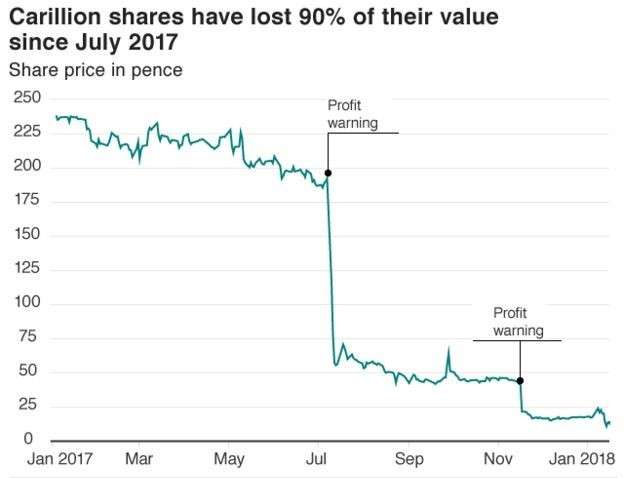

Carillion’s woes became glaringly apparent in July 2017 when the company issued a profit warning. Chief Executive Richard Howson stepped down as it was revealed the company had a £1.15 billion half year loss. Shares dropped by 39% in one day as Carillion attributed its woes to four particular contracts beset by expensive delays and the cost of exiting three Middle East markets. Carillion was pulling out of Qatar, Egypt and Saudi Arabia as plunging oil prices slowed construction across the Gulf region. The increasing cost of oil and other raw materials as well as rising labour costs were also blamed for rendering some £845 million worth of projects, both at home and abroad, unprofitable.

Instead of re-focusing on relatively safer economic territory such as service provision however, Carillion continued to bid for, and win, large scale construction contracts, often with unrealistically low bids. As 2017 drew to a close, Carillion had won a number of new state contracts in the UK- most notably two contracts with Network Rail in November, which it said would generate £200 million over three years and a joint venture contract to supply services for British military sites worth £158 million in September- despite issuing three profits warnings in only five months.

New contracts do not satisfy creditors however, RBS, HSBC, Santander and others refused to loan Carillion any more money. Shares in the company fell by 29% last Friday, as the Cabinet office hosted crisis talks about the potential collapse. That latest drop in stock price means the company’s value had deteriorated by more than 90% in a single year, from £2 billion to £90 million. Ultimately, this deterioration in value was the reason Carillion was forced into compulsory liquidation rather than administration. The company was essentially left with nothing of worth to sell and forced into liquidation as of 6am GMT on Monday. It marks a stunning fall from grace for a 200 year old company which had grown to be one of the leading construction and services companies in the UK.

The Gulf Connection

Substantial delays on three major UK based projects severely affected Carillion’s profits but there was one other significant factor: non payment of accounts by Gulf governments. Before pulling out of three Middle Eastern countries last summer, Carillion had a long standing history in the region, primarily operating through local partnerships (as generally required by law in the Gulf). Carillion continued to operate in the UAE and Oman, winning new contacts in these countries late last year despite local reports that Carillion had not been paid for some two years of work in the country in Oman. This included delayed payment for extensive work on Muscat’s new airport.

Similar reports emerged from Qatar, where Carillion reportedly was not paid £200 million for its work on World Cup stadiums and ultimately ended up withdrawing from the market altogether. Last year, Carillion attributed £314 million of an overall £845 million loss to its Middle East Operations. The company did dispose of half the economic value of its Oman branch, freeing up some £12 million. Despite these non-payments Carillion won a number of large contracts in the Gulf last year. In Dubai, Carillion won a £490 million contract from Expo Dubai 2020. In Oman, Carillion Alawi, in a 50:50 joint venture with the well respected Zawai family, won a design and build contract for a hospital in Salalah worth £240 million; it was also expected the joint venture would be awarded a similar contract in Khasab, said to be worth £120 million. This week, the status of these projects is currently unclear.

Non-Payment in the Gulf

The business landscape in the GCC is changing, following four years of steadily falling oil prices. Governments in the region are cutting back on spending and introducing taxes such as VAT for the first time. Attempts by GCC states to cut government spending have not been generally popular in a region where ruling families and elites have traditionally used oil money to provide generous benefits for their citizens and thus, remain in power.

With this in mind, the payment of foreign contractors is not typically considered a priority by Gulf government ministries. A Reuters report in March of last year found that GCC governments owed contractors a combined figure of £2.5 billion; an estimated 53% of Arab construction firms were reporting experiencing liquidity problems due to this. Operators in Saudi Arabia were particularly at risk last year as the consequences of economic and social changes resulting from Saudi 2030 resulted in the repatriation or deportation of thousands of migrant workers. Non-payment remains the biggest issue facing construction and service companies operating in the GCC however. Though this may improve going forward, with increased efforts at developing Public Private Partnerships when awarding infrastructure projects, there are no guarantees.

Repercussions in the UK

UK Cabinet Officer David Lidington told Parliament on Monday that the government would continue to pay the wages of Carillion staff engaged in public sector work. Thousands of private sector workers however were only given a 48 hour grace period, after which they are likely to be let go. The fate of an estimated 30,000 small firms who depend on Carillion’s business is less clear. Carillion reportedly owes £1 billion to smaller firms, who are now unlikely to be paid, putting thousands of jobs and pensions at risk.

This is in contrast to the bosses at Carillion who continued to award themselves large bonuses throughout 2016 and 2017, despite the deepening fiscal crisis the company was facing and who will also continue to receive their salaries until July or even the autumn, in some case.

Another important question is why the UK government continued awarding contracts –to the tune of £1.3 billion- to Carillion as late as November of last year, while simultaneously preparing contingency plans for the company’s demise.

Carillion’s demise raises serious questions about the privatisation of services in the UK and the manner in which contracts for these services are awarded. Although many people may not have heard of the name Carillion before last week, the company provides services across virtually every sector in the UK- everything from school dinners and healthcare to prison maintenance, road and railway building as well as housing for military families. Other large UK firms such as Nationwide and Centrica, which owns British Gas, have also revealed that they relied on hundreds of outsourced Carillion workers to keep their businesses going.

As well as its state contracts, Carillion held contracts with 25 Councils across the UK. As a consequence of its demise, we may see more Councils giving greater weight to the Public Services (Social Value) Act which came into force in 2013. This law requires Councils to not just accept the lowest tender but to give greater weight to the social benefits of bids; considering smaller, local companies which will provide training and employment to local people for instance.

Although there was no bailout of Carillion, the UK government will have to fill the large gaps in service provisions, attempt to prevent the knock on collapse of hundreds of sub contractors and deal with the resultant pension deficit. The Government is being urged to make a deal with banks that are already pressuring Carillion sub-contractors for payment. One subcontractor told The Guardian newspaper he was owed £1 million by Carillion and has already let ten employees go as he is now unlikely to recoup his costs.

On Tuesday, 16th January 2018, the government ordered an investigation into the conduct of Carillion Directors to be fast tracked; questions will also be asked of accounting firm KPMG which gave Carillion a clean bill of health in March 2017. The role of the pension’s regulator and indeed, some government ministers, are likely to be probed also.

Businesses operating in the Gulf should heed Carillion’s example and be wary when bidding for contracts, given the current economic conditions in the region. Ultimately however, Carillion’s downfall was a consequence of a flawed business model which relied on winning contracts with unrealistically low bids. While other factors certainly contributed to its monetary deficit, had the company been more responsible with its bids since it issued its first profit warning in July 2017, it likely would not have gone into liquidation. The full extent of the consequences of this mistake will unfortunately be felt across the UK over the coming year.

Report written by Louise Hogan