Analysing Protests and Security Across the US

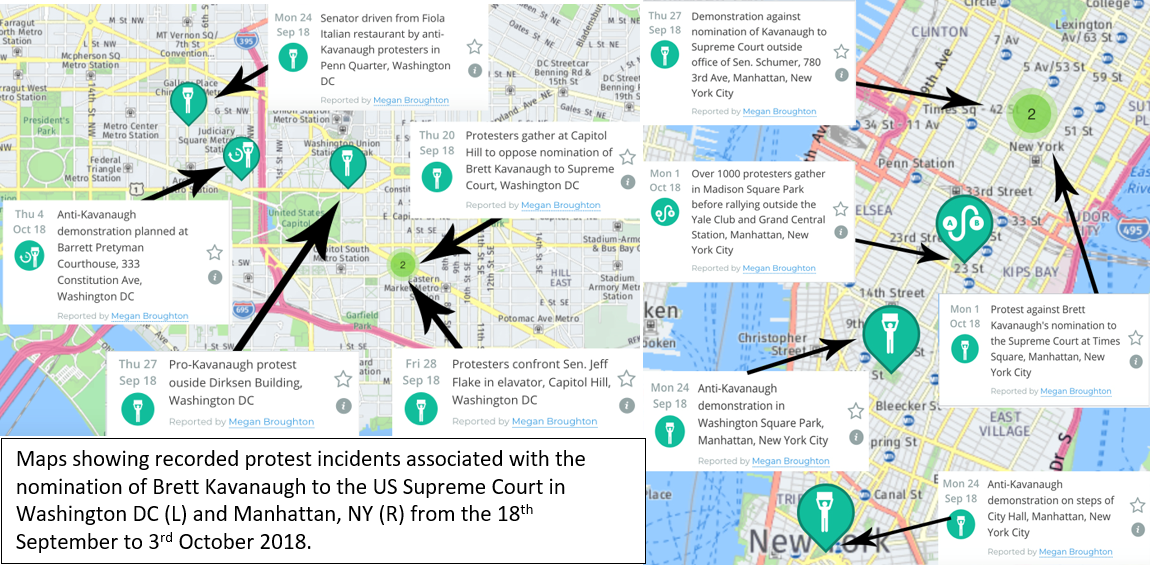

During September 2018, Intelligence Fusion captured information regarding the US-wide demonstrations against the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. In many cases, parallels can be drawn between the nature of these incidents and other protest events that have helped shape the US political landscape over the last few years. It is common knowledge that issues such as race, gender, nationality and economic status have increasingly become more politically charged in the early twenty-first century. As a result, it is arguably more important now for private stakeholders to anticipate and adapt to the public face of politics.

The Recent State of Activism

The US Supreme Court nominee, Brett Kavanaugh (Rep), has now been accused of committing sexual misconduct whilst at high school and university by three women. This comes at an age when the #MeToo movement has spread virally on social media as women attempt to highlight and demand action against the often-unnoticed prevalence of sexual assault and harassment in everyday life. Such movements are not confined to an online presence but have manifested themselves on the streets in the form of mass protest and demonstration.

Subsequently, these trends can be seen to go hand-in-hand with the US’ increasingly vocal political administration; both outrage and agreement between the government and American people feed off each other, producing a fractious national sentiment towards current affairs.

The recent demonstrations have illustrated a resurgence of feminist activist groups such as The Women’s March, which was highly active as the organising force behind feminist anti-Trump protests following the 45th President’s official inauguration. The group has focused its social media presence on forging awareness of potential links between misogyny and the Republican Party, generally appealing to a more left-wing audience of pro-Democrat women. In doing so, many of the issues facing women in recent decades have become politicised; particular political parties become branded as pro or anti women, emotions become captured as actions, and the identities of the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ are produced and circulated. Intersectionality adds to a picture of the identities activist groups form and rally around or against. For example, the Women’s March Twitter page has endorsed it’s support for the Black Women’s Blueprint groups stating:

“ALL women must answer the call from @BlackWomensBP to #MarchForBlackWomen. Join us there.”

Women’s March – (@womensmarch Twitter) – 28th September 2018

In doing so, the group attempts to fuse race into a wider unitary sentiment; the basis of being female becomes a political statement in its own right. Race subsequently becomes another vessel through which a ‘bigger picture’ of opposition to particular forms of authority can be illustrated.

However, the tendency of modern protest groups to manufacture strong identities based on particular ‘categories’ of bodies equally adds to the representation of perceived antagonists. Recent demonstrations have centred around and targeted particular individuals or groups fitting this identity (e.g. the ‘1%’ was the target of the Occupy movement, or the targeting of immigration officials during movements against the separation of child migrants). Consequently, this has strong implications for the protection of targeted identities, and the ways they must present themselves.

Three main strands of investigation are therefore necessary to explore, to ensure security standards are maintained during demonstrations:

1. Identity politics

2. Targeting individuals who fit the ‘bad guy’ mould.

3. Social media

Identity Politics

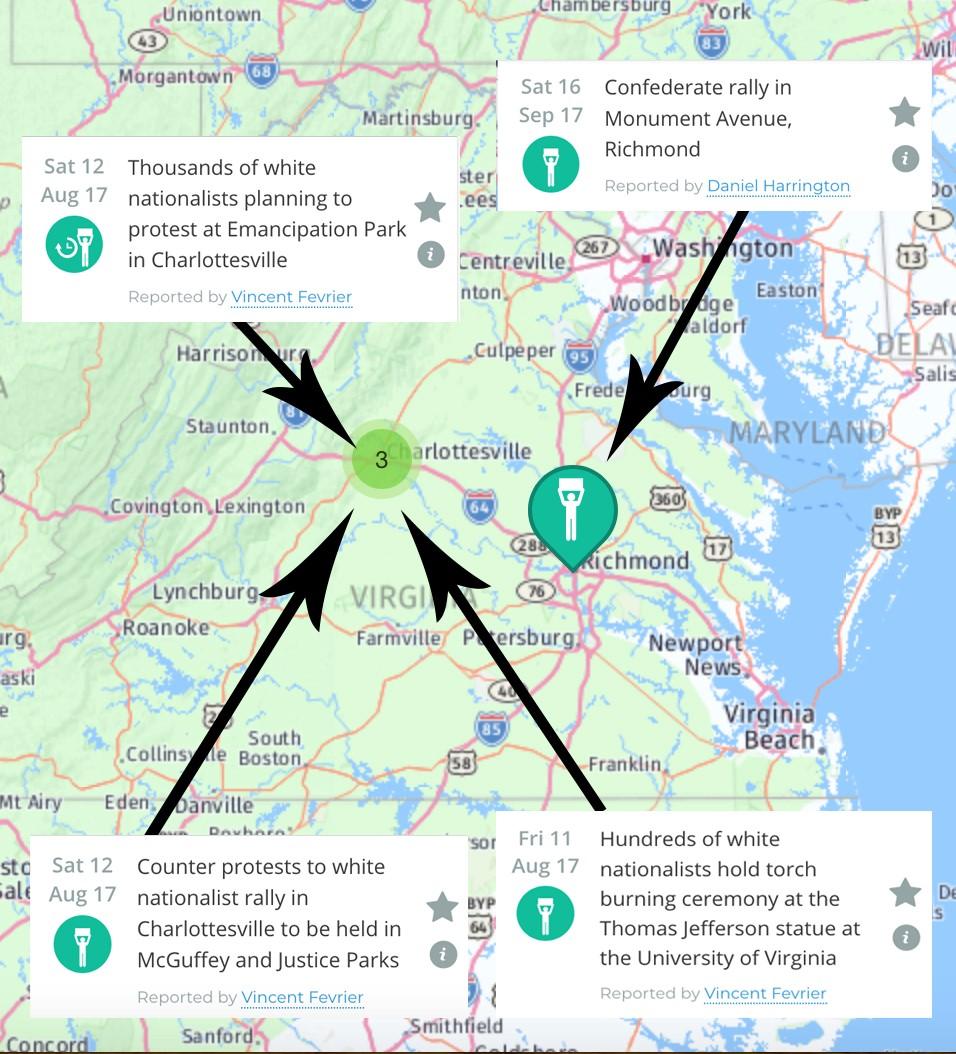

Recent protest incidents have drawn force from strong identities; these are often combined with perceptions of injustice. For example, Intelligence Fusion has captured incidents relating to the Charlottesville protests. Initially breaking out after a ‘Unite the Right’ rally associated with white supremacist and ultra-nationalist groups, counter-protesters from racial justice movements such as Black Lives Matter (BLM) and several anti-fascist organisations marched in opposition, culminating in violent riots. Identity politics proved critical to the triggering of the confrontation; the removal of Confederate monuments shortly beforehand was viewed as an attack on white nationalism and heritage.

This came in the context of heightened racial tensions particularly across the Southern US; in 2014 racially-centred violence broke out in Ferguson following the shooting of a black man by police. Many protest groups mobilized around concerns of institutional racism and the militarization of the police force. Racial identity became both a mark of disparity in society and a rallying point for change to be sought. Nevertheless, the instigation of a spectrum of responses to the shooting meant that outbreaks of severe violence were prominent.

Targeting the ‘Bad Guy’

With racialised, nationalised and gendered activism, the production of a common antagonist has often become crucial to the organisation of moments of action. Following an increasing awareness of the separation of migrant children from their families by US Border Control over Summer 2018, Intelligence Fusion reported thirty-four protest incidents. While these incidents were widely aimed at government ‘zero-tolerance’ immigration policy, protesters assembled under the banner #OccupyICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). Immigration and customs officials proved to be more ‘accessible’ figures through which to direct a wider message of protest against policy. ICE employees were recognisable through their uniforms and places of work, becoming tied up in demonstrations that attempted to disrupt the functioning of ICE operations.

Again, the direct approach of women’s groups to address, and in some cases harass, senators over the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court proves illustrative of this. Protest groups do not only demonstrate towards a political cause, but actively seek to engage with those associated with suppression or the political power to hold influence over their cause.

These individuals or groups no longer appear as distant forces to protesting individuals but can be thought of as somewhat engageable in their role in current affairs.

Social Media

It could be suggested that social media has played a role in the accessibility of public figures to society. Political actors are highly visible on social media platforms, allowing followers to rapidly access information regarding their location and activities. Social media users can contact figures and express political views, often with some degree of anonymity. Simultaneously, social media posts from official figures give their authors a semblance of accountability to the views expressed- generating the Manichean-type identities that protests may identify with or challenge.

Social media’s accessibility has shown its potential as an organising force. From the Arab Spring to the Occupy Movement, the ability for activist groups to appeal to wide audiences and foster a common sense of outrage and commitment to a cause has been critical to the coordination of action. The timing of demonstrations can be shared between individuals, as can an awareness of the whereabouts of protest focal points.

In the age of mass social media, the cliché of ‘fake news’ and misinformation can also prove incendiary to protests. Social media campaigns from foreign agents have been charged with inciting outrage through the spreading of fake statistics regarding racial and political issues. For example, the death of Philando Castile in 2016 became synonymous with racialised police violence in part due to action initiated by a Facebook group, ‘Don’t Shoot’ created by alleged Russian trolls. As a result, this adds an additional layer of complexity to the articulation of demonstrations via social media; the diffusion of anger and strong identities generate conditions wherein current affairs are often a tipping point for action.

Implications for Security

Demonstrations evolve under tense conditions following particular societal and political incidents such as lawful and unlawful shootings, criminal and other accusations, government foreign policy, actual and perceived miscarriages of justice rather than merely in support of a mainstream political party. An awareness of the sensitivity of many of the issues these demonstrations centre on or could centre on is critical in order to foresee cases where this could occur. This coupled with situational awareness could be key to seeing an incident about to develop and reacting quickly to minimise risk.

The centrality of identity politics and social media to demonstrations often means that specific individuals or groups are targeted. This has been direct in some cases; for example most recently in the targeting of senators and their offices by anti-Kavanaugh protesters. In other instances, particular groups have been targeted on the basis of their occupations, such as Law Enforcement Officers and officials working for the Ferguson Police Dept., immigration officials following demonstrations against the separation of migrant families at the US-Mexico border. This has two-fold implications. Firstly, awareness must be placed on the tendency of individuals, companies and organisations to either directly or indirectly broadcast their locations at a point in time via their social media pages. Though often well intentioned, the exposure of locational information via unchecked social media channels could expose private actors to targeted and rapidly arranged demonstrations with the potential for violence. Secondly, the visibility of employees working in professions deemed controversial by some provides another vulnerability in an age where protests may incite violence against those labelled ‘antagonists’. There may be cases wherein it is not advisable for staff to display uniforms or items associated with their profession outside the workplace so as to not draw unwanted attention.

The enhanced ability for protesters to rapidly mobilize through social media platforms has further implications for the use of public and private space. While many demonstrations may plan to occupy public space legally, there have been cases when private properties have been occupied at least temporarily. For example, anti-Kavanaugh protesters recently entered a Washington DC restaurant when targeting Sen. Cruz and in June DHS Sec Kirstjen Nielsen was driven out of a Mexican Restaurant by anti-immigration protesters.

In these cases, it may be necessary to plan security measures beforehand, such as employing screening measures for certain sites in order to restrict access. In particular it could be advisable to allow staff to use alternative entrances to buildings at quieter times to maintain levels of safety.

Finally, an awareness of current affairs and the ‘atmosphere’ on social media is critical to ensure existing security structures and strategies are sufficient; recent recorded protest incidents have shown a tendency to escalate quickly and sometimes incite violent counter protests. Such rapid escalations are often visible through the frequency and types of social media posts and this information could sometimes be used to anticipate some of the higher risk events.