Afghanistan and the Taliban Takeover: What happens next?

Analysing the potential fallout across the globe following the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan.

Twenty years after the US and NATO military intervention in Afghanistan, the Taliban are back in power following the group’s rapid takeover and the collapse of the Western-backed Afghan government. But what comes next?

This series of reports will explore the aftermath of this sudden return to Taliban rule in Afghanistan, tackling both the future outlook for the country itself and the potential ways in which it will impact the rest of the world – from the regional reactions, to the wider impact on global terrorism, and the potential impact on Europe, on China and on US geopolitical influence going forward.

What is the short, medium and long term outlook for Afghanistan?

Short term

Taliban intentions following the capture of Kabul have focused heavily on securing the city from looting and portraying themselves as a legitimate political group.

The group has repeatedly issued statements claiming that in the aftermath of the capture of Kabul, business and NGOs will be allowed to continue to operate (including foreign businesses) and everyday activity may go on. Despite the statements, many Afghans (particularly in urban centres) remain wary and continue to accuse the Taliban of lying in their assurances of amnesty and security. The Taliban were quick to bring in patrols and set up checkpoints across the city with the intention of curbing opportunistic looting and other criminal activity. Despite the law and order focus, multiple reports have been seen claiming that Taliban militants have seized private property and entered business and homes.

Other contradictions of the Taliban’s narrative have also been recorded across the country with incidents such as beatings of women, disappearances and murders being documented. Former interpreters for foreign forces, government officials, critics of the Taliban and ex-security forces personnel are all reported to be at significant risk of arrest or murder by the Taliban. Religious tolerance has also been a key aspect of the Taliban social media campaign following Kabul’s collapse, but again, despite the statements from the Taliban, Hazara communities in particular feel under threat. Fighting in Ghazni Province in the weeks leading to the fall of Kabul included multiple reports of deaths of Hazara civilians at the hands of the Taliban, compounded Hazara fears and has also undermined Taliban promises of coexistence.

Medium term

The initial attempts by the Taliban to maintain a politically legitimate image is expected to wear off somewhat as tensions emerge between locals and Taliban militants in captured territory.

Questions such as education, women’s rights and rights of minorities all act as potential future flashpoints, especially in Kabul and other urban areas. In rural areas, Taliban commanders are expected to vary in their adherence to guidance issued by higher levels of Taliban command, and have generally acted with high levels of autonomy in their decision making in the past. Multiple unconfirmed reports have already claimed that the Taliban have introduced harsh forms of law and order in rural districts, where they face less international media scrutiny and have more autonomy.

The provision of services will also be an important test for the Taliban going forwards, with pre-existing issues such as the security of electricity supply and food supply chains presenting challenges. Already, problems loom for Afghanistan regarding food supply with the World Food Programme (WFP) warning of shortages as early as September 2021. Food supply-related problems have been further compounded by Kazakhstan’s decision to redirect wheat exports away from Afghanistan to new markets following the Taliban takeover.

Years of war and frequent roadside IED attacks have taken its toll on Afghanistan’s roads which remain in a poor state. The Taliban have attempted to quickly begin road improvement projects, although the extent of these projects across the country is unclear.

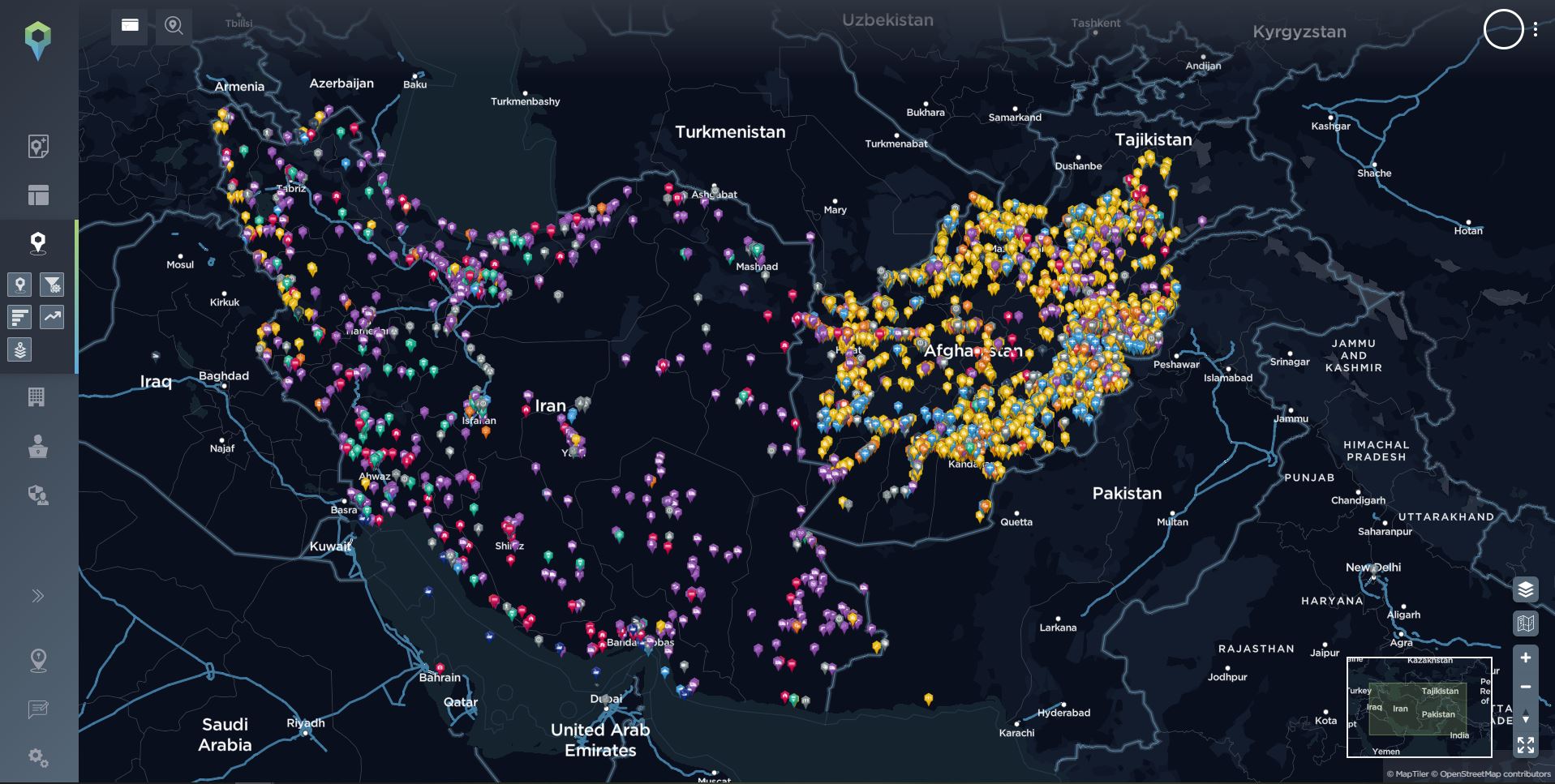

Locations of clashes in Baghlan Province, where militias have captured territory in recent fighting. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

At the time of writing, the Taliban are still yet to have seized control of Afghanistan’s Panjshir Province. The province is currently controlled by local militias with a small input from remaining security forces personnel. Commanders from the province itself (including the son of Ahmad Shah Massoud, famous Tajik militia commander) have vowed to protect their province and have carried out offensive operations in nearby Baghlan province. With the overwhelming Taliban advantage militarily and the lack of foreign support for militias in Panjshir, it is possible that some form of agreement may be reached in which the province is permitted to retain an element of autonomy from the Taliban leadership. Reaching an agreement may divide Taliban supporters, with some demanding no negotiations with the militias. At the time of writing, talks are reported to have taken place between Panjshiri militia leaders and Taliban commanders with little progress.

Clashes between the Panjshiri militias and Taliban militants have so far been restricted to the Banu, Pul-e-Hisar and Deh Salah districts of Baghlan province, north of Panjshir. Clashes have also been reported nearby in the Anjuman Valley, with few details available regarding territorial control or the scale of the clashes.

Long term

It is believed that the Taliban control of Afghanistan invites increased influence in the country from terror groups such as Islamic State and Al Qaeda, both of which already have a presence in the country.

Al Qaeda in particular have maintained a close relationship with the Taliban throughout the NATO intervention via personal relationships with high profile members of the Taliban such as Khalil Haqqani and Sirajuddin Haqqani. Closer coordination with regional Al Qaeda elements such as Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) is also expected.

Other regional groups such as Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) who straddle the Afghan-Pakistan border will also use Afghanistan as a springboard for attacks into Pakistan (mostly from Afghanistan’s Kunar Province) despite the Taliban denying the TTP operates in large numbers in Afghanistan. IS-KP on the other hand is expected to bide its time, with its long term strategy being to potentially exploit any Taliban failures and to recruit additional cells, with a potential to recapture physical territory in the future. The group is also believed to have received a boost from mass prison releases during the Taliban offensives. IS-KP’s suicide bombing at Abbey Gate of Hamid Karzai International Airport showed the group is seeking to act as a spoiler by targeting coalition forces and simaltaneously undermining Taliban claims to be capable of providing security. An unstable Afghanistan where the Taliban struggle to maintain security (and therefore political legitimacy) would suit IS-KP strategic interests and would also potentially deter regional states from supporting the Taliban. With this in mind, IS-KP will carry out similar attacks as those seen in Kabul via a network of radicalised cell members recruited from within Afghanistan.

Combat operations carried out by foreign countries are considered very unlikely, with regional powers appearing willing to cooperate with the Taliban and NATO states lacking the will to re-engage militarily. With this in mind, drone strikes carried out by the US targeting known terror suspects have not been ruled out by US officials, who remain wary of the potential for terror groups to grow in Afghanistan.

Lastly, whilst the Taliban have historically been an isolationist group with few involvements in international affairs, their seizure of Afghanistan will force the group to take up some form of foreign policy. As part of this, the Taliban have repeatedly claimed that they are willing to take on foreign assistance in order to help rebuild the country via NGO support and infrastructure projects, however, their ability to attract foreign development and support depends heavily on their ability to secure the country and avoid becoming an international pariah due to human rights violations. With this said, states in the region such as China, Pakistan, Russia and Iran have all expressed interest to varying degrees in working with the Taliban. Coordination may come in the form of assistance in extracting Afghanistan’s mineral deposits, infrastructure projects or technical expertise.

How have Central Asian governments responded to the Taliban takeover?

Whilst specifics regarding the respective responses of the Central Asia governments have varied, all share similar concerns over the potential impact of the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan.

Central Asian states remain wary of the presence of an extremist islamist group at their border in the form of the Taliban, and have long since been concerned about the impact this may have on the movement of militants across the Afghan border. Despite the number of Central Asian nationals fighting with the Taliban in Afghanistan being relatively low, Taliban alliances and relationships with Central Asian militant groups such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and Jamaat Ansarullah will provide cause for concern.

Central Asian states must also balance their own concerns with the reality that Russia has maintained significant influence in the realm of security in the region and continues to seek to maintain this role. Russia, like the Central Asian states, remains wary of the Taliban due to their relationships with militant groups in Afghanistan as well as Al Qaeda. However, Russia has also expressed an interest in working with the Taliban in order to maintain the security of Central Asian (and by extension, Russian) borders. Recent military drills involving Russian personnel were held close to the Afghan border in both Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, seemingly aimed at cementing Russian influence in security provision. The drills themselves were relatively routine, but their timing also suggests that Russia, whilst open to coordination with the Taliban, will not accept a security spill over into the Central Asia region. The Taliban have traditionally focused almost exclusively on affairs within Afghanistan’s borders, meaning that security spill over as a result of Taliban operations is rare, and future confrontation along the border is considered unlikely.

Tajikistan

Tajikistan has long since been wary of the presence of Taliban militants on its border and has stated that it will not recognise a Taliban-only government.

Tajikistan’s more confrontational stance regarding the Taliban, when compared to the stance of other states bordering Afghanistan, reflects their own security concerns relating to the presence of ethnic Tajik militants in Afghanistan. The Taliban seizure of the north prior to the capture of Kabul solidified the concerns of the Tajik government regarding the presence of Tajik militants, after reports claimed the Tajik Jamaat Ansarullah group (allied with the Taliban) had been placed in charge of several Taliban controlled districts along the Tajik border. Whilst Jamaat Ansarullah is not a large group, videos have been recorded in northern Afghanistan in which Tajik fighters affiliated with the Taliban explicitly threatened Tajikistan and other Central Asia states, causing Tajik authorities to take the threats seriously.

With Tajikistan sharing a border with Afghanistan, the flow of refugees also plays an important role in dictating Tajik policy regarding Afghanistan. Tajik media reported in July 2021 that authorities in the Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) had called for additional resources to handle the potential influx of refugees from Afghanistan as they anticipated further collapse. As well as civilian refugees, Tajikistan has taken in large numbers of Afghan military personnel during the Taliban capture of districts in the north. The flow of surrendering Afghan personnel into Tajikistan began somewhat slowly and ad hoc, but culminated on 15th August when 16 Afghan aircraft of various types landed at airfields across Tajikistan. Tajikistan has generally accepted both civilians and military personnel escaping from Afghanistan, but like other Central Asian states, is concerned about the impact this may have on their neutrality in fighting in Afghanistan and the impact this may have on their own security.

Uzbekistan

Like Tajikistan, Uzbekistan has also witnessed a large number of Afghan personnel and civilians attempting to retreat across the border to avoid fighting.

Whilst Uzbekistan has in instances allowed the retreat, Uzbek border guards have generally taken a more hardline stance than authorities in neighbouring Tajikistan and are reported to have refused entry on multiple occasions. In mid-August 2021, Uzbek border guards are reported to have prevented civilians and militia commanders loyal to the ethnic Uzbek commander Abdul Rashid Dostum from crossing into Uzbekistan (although Dostum and Atta Mohammad Noor are reported to have been allowed entry.) Other videos showed large numbers of vehicles belonging to Afghan personnel abandoned at the Hayratan border crossing, with the occupying personnel allegedly permitted to enter Uzbekistan.

Despite Uzbekistan’s harsher stance regarding the retreating Afghan military personnel, Afghan forces still attempted and succeeded to fly aircraft to Uzbek airfields in order to prevent them from falling into Taliban hands following the loss of territory across the north. In one high profile incident, an Afghan Air Force aircraft crashed in Uzbekistan near to Sherabod, allegedly after being shot down by Uzbek forces for attempting to violate Uzbek airspace. Other reports claimed that the plane crash landed after running out of fuel, with additional unconfirmed reports claiming that the plane collided into an Uzbek plane, causing the crash. The incident highlighted Uzbekistan's reluctance to act as a safe haven for Afghan government forces, evidently concerned that such a status may violate Uzbekistan’s neutrality in the eyes of the Taliban.

Uzbekistan has generally appeared more willing to coordinate with the Taliban then neighbouring Tajikistan, but is still expected to approach the Taliban with caution. The Taliban’s relationship with the IMU may jeopardize potential coordination between the Taliban government and Uzbekistan, however, as long as the IMU continue to not carry out operations in Uzbekistan, and the Taliban can continue to provide security along Uzbekistan’s border, the coordination to some degree is expected to go ahead.

Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan

Turkmenistan’s inner government workings remain typically opaque, however, much like Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan has shown a willingness to cooperate with the Taliban across their border.

Turkmenistan’s willingness to work with the Taliban can be partly explained by their increased economic involvement in Afghanistan via electricity supply and the much-discussed TAPI pipeline project. Turkmenistan sees close coordination with the new Taliban government as a way of securing their own economic interests and are expected to continue to be open to additional meetings with the Taliban.

With Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan not sharing a border with Afghanistan, their own responses have been less urgent. Both countries have generally restricted their responses to statements in which they claim to be paying close attention to the situation in Afghanistan. Kazakhstan does however have limited economic interests in Afghanistan as Kazakhstan is responsible for a large proportion of Afghanistan’s imported wheat. Following the Taliban takeover, Kazakhstan is reported to be seeking new markets for its wheat crop and is diverting its exports away from Afghanistan due to concerns over the Taliban’s ability to pay for the imports due to sanctions.

What will the impact of the Taliban takeover be on Europe?

The withdrawal from Afghanistan and the subsequent return of Taliban rule will amplify already significant issues facing Europe.

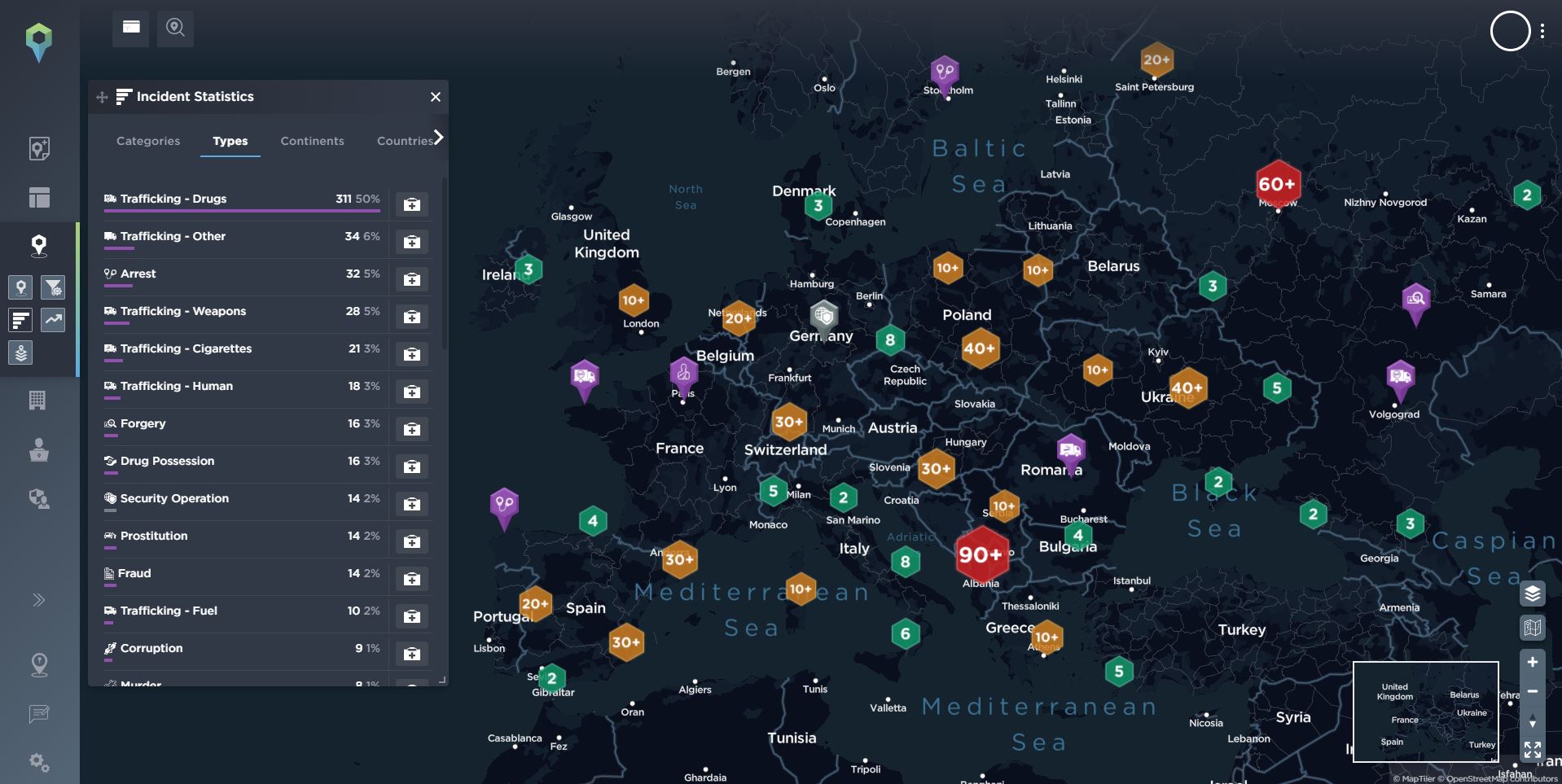

The most significant issue that may be exacerbated is organised crime and the opportunity for such networks to profit significantly from the chaos and transfer of power in Afghanistan. Activity from organised criminal groups stretches across the entire continent and predominantly consists of drug and human trafficking.

Drug Trafficking

Drug trafficking across Europe has largely consisted of marijuana trafficking along with the importation of hashish from North Africa and cocaine from South America. Drug trafficking networks are frankly spoiled for choice in terms of points of entry for importing large quantities of drugs. Heroin is a regular feature in incidents but is rarely in the same quantities as marijuana, cocaine and hashish.

Overview of incidents relating to organised crime across Europe in 2021. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

One of Afghanistan’s most infamous exports is opium. Given the hostility towards the Taliban across the globe, the Taliban will likely need to trade in black markets in order to financially sustain itself, especially if, as seems likely, sanctions are imposed, making the export of opium and other narcotics too profitable to resist, which, given the widespread activities of organised crime across Europe, would likely lead to an increase in narcotics originating in Afghanistan reaching the continent. A 2020 UN Security Council report estimates that the Taliban already earns a combined annual revenue of between 300 million and 1.5 billion USD, the bulk of which comes from heroin cultivation and production - although methamphetamine has also emerged as a profitable source of income for the group in recent years.

Human Trafficking

The second major area that organised crime profits from in Europe is human trafficking. Human trafficking has been an ongoing issue across Europe; in addition to the ‘push-factors’ driving migration from areas of high instability and poverty, ‘pull-factors’ such as the European Union’s (EU) inviting policies for migrants of all motivations, lack of coordination and/or will to enforce borders and assistance provided to migrants by activist groups gives an almost constant supply of people willing to pay traffickers to enter Europe. Shown in the imagery below with red arrows, multiple routes exist which allow entry into Europe and reach as far as the UK via the English Channel. Additionally, a route via Belarus appears to be emerging as President Lukashenko and his government appear to be using Belarus as a thoroughfare for migrants as a form of retaliation for sanctions imposed against it (a similar strategy Turkey uses with the Balkan Route and Greek Islands).

A map of the reported human trafficking incidents alongside the most common human trafficking routes in Europe. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

The confronting images of Afghans - mostly fighting aged males - trying to stow away on departing US military aircraft from Afghanistan, the very real threat to Afghan women and girls from the well-known interpretation of Sharia rule that the Taliban will impose, and the threat to those who may be seen as ‘collaborators’ with the US-backed regime, will likely see an influx of Afghans trying to enter Europe via these trafficking routes, especially with the end of evacuations from the country following the final US withdrawal on 31st August. Even before the Taliban takeover, almost 18.5 million people - or half the country’s population - were reliant on foreign aid; the sudden collapse of central government, the freezing of financial reserves, and the uncertain security situation for NGOs providing aid in the country mean a humanitarian crisis to further fuel this mass exodus of people seems likely to be around the corner, too. Considering this will increase both the supply and demand for human traffickers from migrants (be they asylum seekers, refugees or the vast numbers of economic migrants), organised crime networks in Europe will be anticipating very lucrative times ahead.

This anticipated increase in human trafficking into Europe will also see spill-over effects, the most profound being an increased threat of terrorist attacks from Islamic Extremists; the continent already faces a significant threat from both homegrown and migrant perpetrators. Furthermore, a factor which is rarely (if ever) acknowledged when it comes to Islamic Extremism is how migrant perpetrators have been able to easily pose as asylum seekers or refugees in order to enter Europe due to the prior mentioned ‘pull factors.’ Once they have gained refugee/asylum seeker visas these terrorists have been able to travel throughout the continent almost undetected and carry out attacks or simply hide; as shown by the incidents with yellow borders. With the anticipated increase in migrant numbers coming to Europe from Afghans fleeing Afghanistan, it is highly likely that Islamic Terrorists - of any nationality - will find it easier to hide amongst migrants and thus infiltrate Europe to carry out attacks.

A selection of significant incidents of Islamic terrorism in Europe. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Overall, the withdrawal from Afghanistan and return of the Taliban will have significant effects on Europe. The most significant will be the anticipated increase in organised crime activity due to lucrative opportunities for increased drug trafficking from opium and what could be described as an upcoming explosion of human trafficking across the continent as Afghans fleeing their country will add to already high numbers of migrants coming into Europe. Furthermore, this increase in migrants will also mean an increased threat posed by Islamic Extremism.

How will the Taliban's control in Afghanistan impact China, Taiwan and Asian geopolitics?

China’s primary strategic aim in Afghanistan will be to ensure stability to secure both its Western province of Xinjiang and its significant infrastructure projects in Pakistan against extremist or separatist threat.

Of secondary but still significant importance will be China’s economic interests in Afghanistan, both realising stalled pre-existing mineral extraction projects and securing further interests, either as stand-alone projects or as an expansion of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). In order to achieve these aims China will look to aid the establishment of the new Taliban government by providing political recognition, economic aid, and investment in exchange for influence and security cooperation. China is well positioned to offer this aid, having established bi-lateral ties with the Taliban in 2014 and, being avowedly non-interventional, China is unlikely to place caveats or governance demands on any aid it gives, unlike Western powers. Diplomatic recognition is to be expected once the Taliban is established and China may well seek to champion the new government on the international stage to some degree. However, much of the likely success and degree to which Beijing will pursue these means depends on the Taliban and whether they can establish control over the country, avoid further significant conflict and avoid becoming a pariah state through human rights infringements.

Security

The perceived separatist threat from the Uyghur population, which could use Afghanistan as a base to carry out operations in neighbouring Xinjiang, is of significant concern to Beijing.

China has claimed there to be a Uyghur separatist threat in Afghanistan since the 1990s and pushed to have the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) placed on the UN Security Council’s list of terrorist groups in 2002. Although there remains little verified information on the size and capabilities of ETIM - which is often referred to as being the same as or part of the Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP) - China has already established a security presence in and around the Wakhan corridor and will seek to maintain or increase its presence in Badakhshan province to ensure control of the mountainous border region. China also has a growing security cooperation with Tajikistan, where it has established a base in the Pamir mountains from which the People’s Armed Police (PAP) conducts patrols, and will continue to build on this relationship with further counterterrorism exercises, such as those seen outside Dushanbe in August. Afghanistan was made an observer state of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in 2012 and it seems likely that this will be extended to a Taliban government, with the possibility of full membership in the longer-term should there not be any objections from other member states.

Of further concern to China is the security of its flagship CPEC projects, which form the centrepiece of the greater Belt and Road Initiative (BARI). These projects have suffered attacks from both terrorist groups in Sindh and Balochistan provinces as well as from Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). A stable government in Kabul which Beijing can rely on to at least curb extremist activities within their borders would be a significant step towards securing these interests. However, while Islamist groups within Pakistan aligned with the government have been almost silent on issues such as the persecution of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, there is a risk that with the removal of Western forces from the region, groups outside the control of Islamabad such as TTP, Al-Qaeda and Islamic State could turn their eyes to the growing Chinese presence and increase their anti-Chinese propaganda and attacks. Should this be the case it is unclear how much influence a Taliban government will be willing or able to exert.

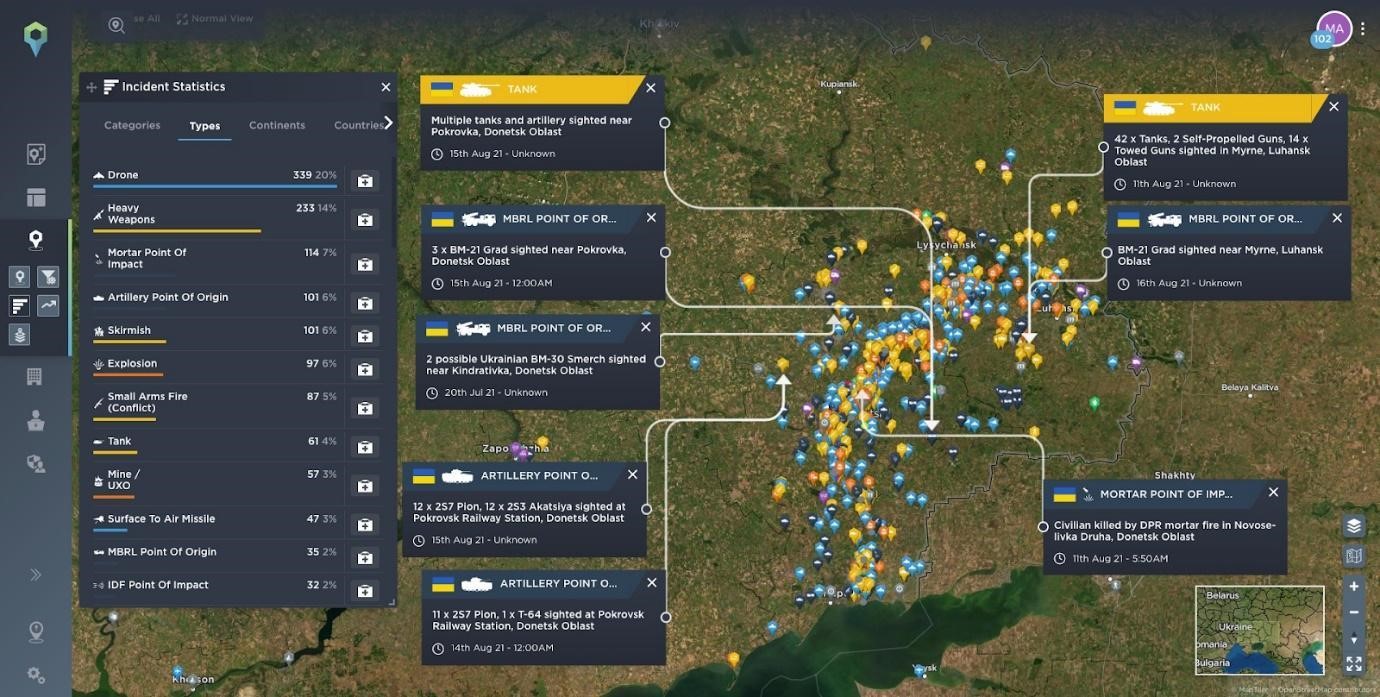

Ab example of recent attacks on Chinese workers in Pakistan. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Military aid in the form of arms, training and even intelligence support should not be ruled out in the long term, but China will seek to maintain a light footprint and is highly unlikely to commit troops to any stabilisation operation in Afghanistan beyond a counterterrorism presence. Even should Chinese economic interests in Afghanistan grow, China has demonstrated a high tolerance for attacks on its nationals in Pakistan and would likely be content to rely on credible security actions by the Taliban to secure its interests rather than commit its own military or police in significant numbers. If nothing else, China will not wish to be distracted from its greater strategic interests of Taiwan and the South China Sea.

Economics

Although many commentaries emphasize Beijing’s desire to exploit Afghanistan’s purported 3 trillion USD in mineral wealth, it is unlikely that China will rush to pour significant resources into Afghanistan.

Until the Taliban government can be properly established and demonstrate at least an acceptable degree of control over the majority of the country, Chinese companies will likely limit themselves to realising pre-existing agreements such as the Mes Aynak copper mine in Logar province, originally agreed with Metallurgical Corporation of China and the Jiangxi Copper Corporation in 2008, and the 400 million USD oil concessions in Faryab and Sar-I-Pul. Given Afghanistan’s rugged geography and lack of infrastructure, transportation projects will be a necessary precursor to any larger mineral extraction or energy investments, and projects such as the 5 million USD road through the Wakhan corridor begun by the Ghani administration are likely candidates for completion.

Should the Taliban prove itself to be a reliable partner, Beijing will not wish to lose out on the potential riches of Afghanistan to other prospective investors such as Russia, Iran, the Arab states or even India. Longer term investment in the country could give Chinese companies greater access to strategically important minerals whilst simultaneously providing much-needed revenues and infrastructure for the Taliban government, economic opportunities for the population of Afghanistan and increasing Beijing’s influence in Kabul.

What is Iran's future Afghanistan plan?

The twin issues of the flow of migrants and narcotics across the border are likely to play a role in Iran’s immediate plans for the new reality in Afghanistan. Iran currently hosts one of the largest refugee populations in the world, the vast majority of whom are from Afghanistan - around 780,000 registered Afghan refugees and between 2.1 to 2.5 million undocumented Afghans live in Iran. Iran also currently has one of the highest rates of drug addiction due to being a main conduit to Western markets for opium. This means Tehran will likely attempt a pragmatic approach to dealing with the Taliban in order to curb this flow of people and narcotics.

What will largely shape the future Iranian response though, will come down to a few key factors: Iran’s own national security concerns, including the internal challenges posed by various ethnic groups within the country; its attitude towards the Taliban, one of hostility prior to the US invasion, but which has evolved to something of a rapprochement over the last decade, with some degree of cooperation aimed at weakening the US presence, and more recently with a number of meetings in 2021 between between Iran and the Taliban; Iran will also be keen to work with the Taliban to avoid any sort of renewal in the group’s prior relationship with Saudi Arabia, and it will also be keen to seek assurances from the Taliban that they will reign in any militant Sunni groups that may spill over the border; the likely economic sanctions faced by the two countries also mean that an increase in trade between the two will be mutually beneficial in order to mitigate their effects.

However, the degree to which this can be realised will likely depend on the treatment of the sizeable Shiite minority in Afghanistan, which Iran will be keen to protect; there is the potential for future conflict - or a resumption of prior hostilities - should the majority Sunni Taliban commit abuses against the Shia community. Iran also fears Islamic State gaining a foothold in Afghanistan that could be used as an operational springboard to target the country, while the group may also routinely target Shia Afghans - should working with the Taliban fail to curb the presence of Islamic State on its border, Iran may instead turn to direct military action against the group. Meanwhile, the issue of water security - previously a driver of hostility between Iran and the Taliban in the late 90s - still looms large.

For a complete report on Iran’s Future Afghanistan Plan, including:

- Iran’s national security concerns

- Iran’s attitude towards the Taliban

- Iran’s aim to protect and exert control over Afghan Shiites

- The potential for Iranian conflict with the Taliban

- The issue of potential renewed Saudi support for the Taliban

- What would an Iranian invasion of Afghanistan look like?

What will be the impact on US geopolitical influence across the world?

The US and NATO’s withdrawal after 20 years of attempted nation building in Afghanistan will not go unnoticed in Moscow and Beijing, who are already preparing to normalise relations with the Taliban government. Both Russia and China will likely use this example to undermine or intimidate governments seen as client states of the United States such as in Kiev and Taipei, and portray the US as a weak and unreliable ally.

As an immediate reaction, it is likely that state sponsored information campaigns will escalate in those countries, aimed at undermining faith in local governments and populations that the US will stand by and support them militarily or politically in any future confrontation with Russia or China. A recent post by The Global Times, a tabloid controlled by the Chinese Communist Party, warned Taiwan against continuing its reliance on the US as an ally, and adding that Taiwan will encounter a situation similar to the one that has unfolded in Afghanistan. Both Russia and China will intend to shape perceptions in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Southeast Asia that local governments should rethink their relationship with the US and pivot away from alliances with the US or NATO.

Europe

Initially looking at Europe, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan is certainly likely to affect its geo-political influence. The biggest effect may be a credible perception by European allies that support from the US will likely falter in the face of existential threats; a perception of the abandonment of locally employed interpreters, contractors and others who worked directly with the US in Afghanistan providing one example. As this perception will shake the confidence of US support among allies, it will simultaneously bolster the confidence of its geo-political rivals - namely the Russian Federation.

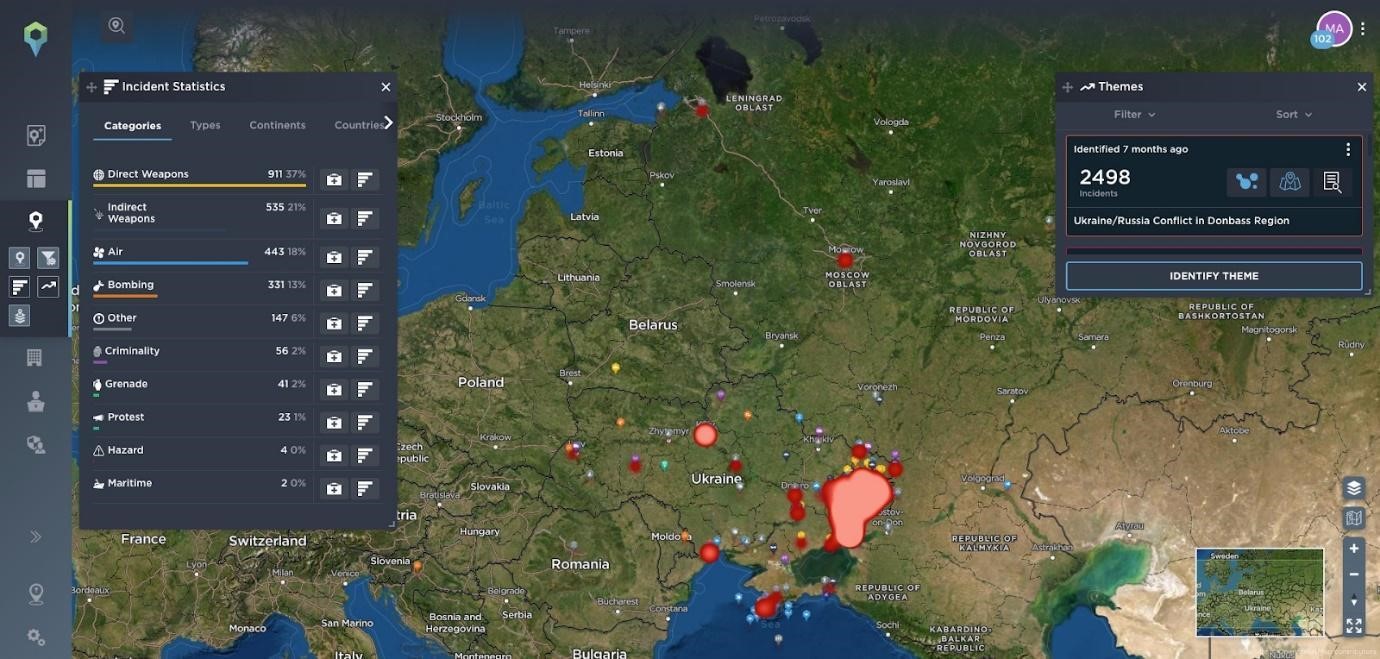

Heatmap showing the concentration of incidents reported in Russia and Ukraine. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Such a perception is likely to be the most profound in Eastern European countries, with Ukraine currently being the most at-risk with its ongoing war with Russia-backed separatists in its Donbass region. Fighting in the region has been gradually increasing and nowadays features artillery fire and increasing amounts of tanks, artillery, anti-aircraft and rocket launch systems being brought towards the Donbass front line. Russia has been increasing its espionage efforts in Donbass’ surrounding regions, and the Nord Stream 2 pipeline’s upcoming completion will reduce Russia’s dependency on functioning gas transmission lines.

The recent conflict concentrated in the Donbas region of Ukraine. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Prior to the Afghanistan withdrawal, Ukraine was receiving support from the US in terms of joint military exercises and arms supplies which included Javelin Anti-Tank missiles. Such support would appear to play a major role in keeping Russian-backed separatists and the various tanks and self-propelled artillery in their current areas.

However, with the withdrawal from Afghanistan and the real and perceived abandonment of Afghans by the US, US allies in Europe - Eastern Europe especially - will likely be considering whether they can realistically count on US support should Russia become emboldened and increase aggressive foreign policy objectives in Europe.

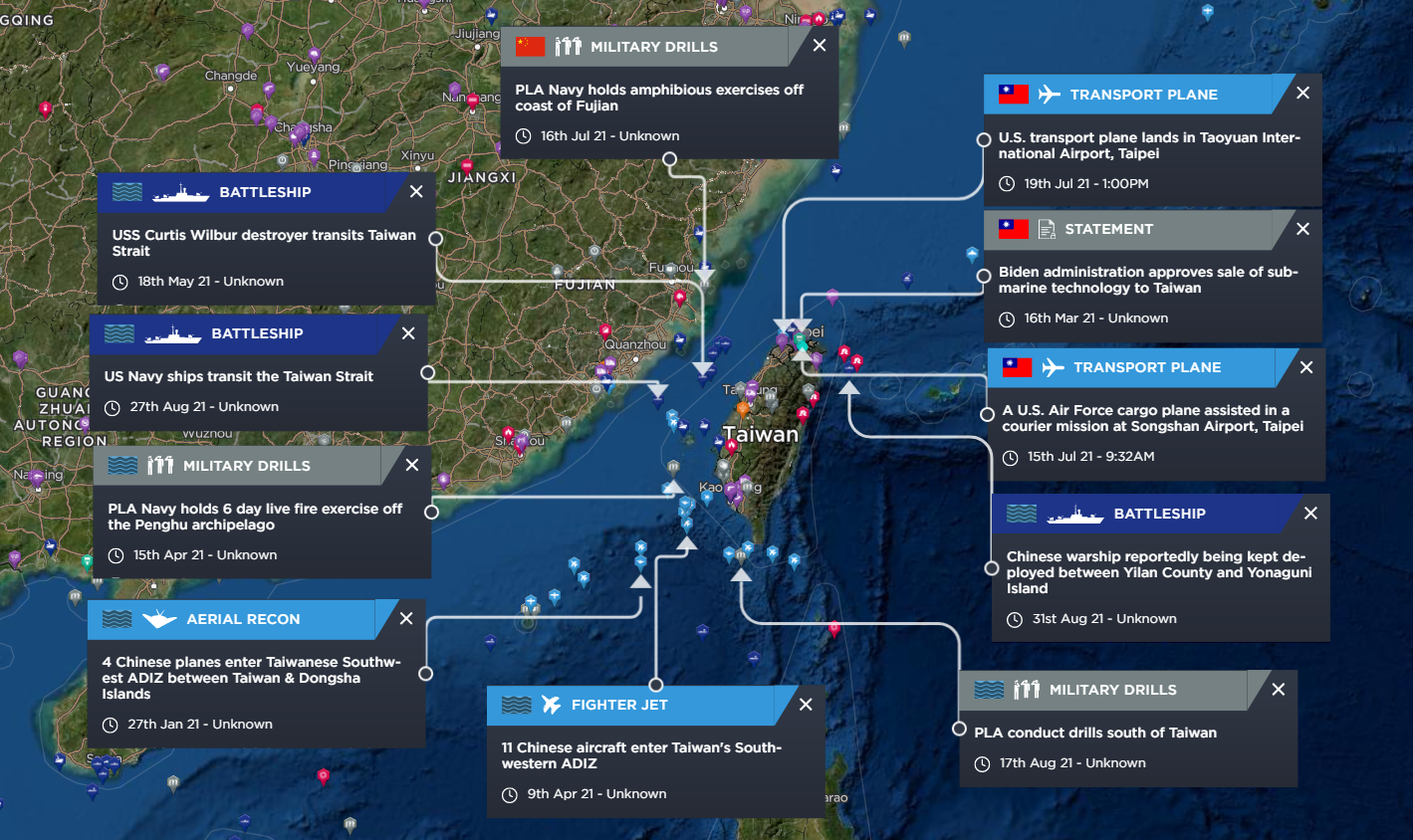

Asia

The US withdrawal may possibly embolden China not only in foreign policy issues with Taiwan but also Central Asia. China will likely increase military exercises in the Taiwan Strait along with a continued policy of increased air incursions into Taiwanese airspace aimed at eroding and exhausting the Taiwanese military. With no US military bases on the island of Taiwan it will be harder for the US to convince China that, post- Afghanistan, the US government will be a reliable long term ally of Taiwan and provide immediate military support in the event of any potential conflict.

Another key perception taken from the Afghanistan withdrawal is the apparent view that if the local population is not willing to fight for its own sovereignty, then neither will the US government. China may apply this sentiment to Taiwan, and therefore will likely increase attempts on both political, diplomatic and economic fronts to encourage the Taiwanese population to support reunification with the mainland, and weaken pro-independence feeling within the state.

A map highlighting a selection of significant incidents in the Taiwan Strait in 2021. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

However, while in East and Southeast Asia the withdrawal also plays into the narrative that the US is in decline and China ascendant - which both Chinese and Western media have picked up on and expanded to portray the US as an unreliable ally - it is questionable that this sentiment will be prevalent in the more sober circles of official Chinese policy-making, and in fact the withdrawal may lead the US to refocus its efforts on more traditional security concerns, not least strategic competition with China. Nevertheless, Chinese propaganda can be expected to take advantage of any US loss of face to enhance its own standing and attempt to undermine that of the US in the region.

The degree to which the collapse of the Western-backed government in Afghanistan may cause concern with the long-established treaty allies of the US in Asia is difficult to quantify, but it is unlikely to undermine the overall confidence of governments in South Korea, the Philippines or Japan in their defence relationship with the US. The unwillingness to continue a 20-year nation-building project in South Asia cannot fairly be compared to the willingness to aid the defence of a treaty ally in the Western Pacific, particularly in a conventional war with consequences to the global economy and balance of power. This rationale can credibly be extended to Taiwan, where the ability to deter against a possible invasion by the mainland is subject to far more significant factors than the government in Kabul. Where the narrative of a declining US unwilling to defend its allies may gain some traction is in the disputed area of the South China Sea, where comparatively weak claimant states have consistently been the victims of China’s increasingly belligerent actions despite US objections. Even so, recent events in Afghanistan are unlikely to have any bearing on the continued issues of disputed sovereignty.

To allay any concerns there may be, the US could well seek to reassure regional allies in the coming months, and an increase in Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS), diplomatic dialogue and military exercises into 2022 seems likely. Such actions will no doubt bring the obligatory condemnation from China and corresponding military signalling, most likely in bouts of increased air incursions across the Taiwan Strait aimed at eroding and demoralising Taiwanese air defences, continued naval and amphibious exercises, and potentially further missile tests such as that of the DF-21D “carrier killer” ASBM.

Within the Middle East, Israel may also have concerns regarding the US withdrawal. David Horowitz in The Times of Israel stated, for instance, that, “for Israel………the US mishandling of Afghanistan also shocks and horrifies because it gives succour to terrorist groups and extremist regimes”. The Israeli government will be debating whether US military and political support will be as concrete as in prior administrations, or if it will be willing to commit to the sort of military footprint previously seen in the region, in the event of a regional conflict with Hezbollah or escalation with Iran.

Will we see a regional economic and geopolitical fallout from the Taliban takeover?

The US withdrawal from Afghanistan will reduce US influence in the Middle East and Central Asia and, in turn, increase the influence of local actors such as Pakistan and Iran. The US may likely try to reassert some form of military footprint in neighbouring states such as Uzbekistan in order to be able to have the capacity to carry out any future intelligence gathering or targeted strikes against any future emerging terrorist threats in Afghanistan although this may likely increase tensions with Russia who view the CIS states as their own sphere of influence. However, any large-scale US military presence will be compelled to retreat to the Gulf region and Diego Garcia.

India

For India, the collapse of the Afghan government has been a huge setback.

India spent 3 billion USD on infrastructure projects over the last 20 years in Afghanistan as well as training Afghan military personnel and providing education scholarships to thousands of Afghans. India may now try to strengthen its alliance with the US now that China will be viewed as increasing its influence in South Asia. New Delhi will be aware that both Pakistan and increasingly Afghanistan will now fall under Chinese economic and political influence. With the continued development of Gwalior port and China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, Afghan products will be able to transit through the port, giving landlocked Afghanistan an important trade route as well as decreasing China’s reliance on oil passing through the Straits of Malacca which India can threaten in the event of any conflict with China from its base on Great Nicobar Island.

Pakistan

US relations with Pakistan will likely need to be recalibrated. Between 2002 and 2018, the US government gave Pakistan more than 33 billion USD in assistance, including 14.6 billion USD in Coalition Support Funds paid by the Pentagon to the Pakistani military until the Trump administration severely cut military aid and assistance.

It is likely that a heavily in debt Pakistan will increasingly come to rely on China both from an economic and military perspective. Pakistan has already sought to purchase large scale Chinese military equipment such as J-10 (CE) fighter jets and this trend will likely only increase, as well as joint exercises.

Pakistan will look favourably on the US withdrawal, with its presence in Afghanistan having allowed India to expand its influence in the country as well as offer a potential haven to Pashtun and Balochi nationalist groups. Many Pakistani politicians have expressed open support for the Taliban and it is likely that Pakistan will attempt to increase its influence in Kabul in the coming months exploiting the political vacuum left by the departure of international embassies.

Pakistan will also focus on preventing any Islamic extremist groups that could threaten internal security within Pakistan, such as the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a Deobandi extremist group that operates from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province along the Afghan border and the Pakistani Taliban, from establishing bases of operation in Afghanistan. These groups will likely aim to exploit the military vacuum left by the US withdrawal to establish training camps or bases in remote areas along Northeast Afghanistan. A lack of US presence and cooperation in the border areas may also allow hardline groups such as Islamic State or Tehreek-e-Taliban to regroup and reinvigorate with increased freedom of movement in eastern Afghanistan.

Terrorist related Incidents in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province during 2021. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Both Pakistan and Iran will also likely feel the immediate burden of a refugee crisis as Afghans loyal to the old government seek sanctuary. Pakistan will be especially keen to seek political stability in Afghanistan and has already begun focussing on building a regional consensus to recognise the Taliban government.

China

From an economic perspective, Afghanistan is estimated to hold up to three trillion USD worth of minerals as well as potentially the largest lithium deposit in the world concentrated in three regions; Ghazni province in the east and Herat and Nimroz provinces in the west. With China embarking on a very significant green energy development program these deposits may give China access to vast amounts of raw materials from a bordering country.

Supplies of minerals such as iron, copper and gold are also scattered across the country. Controlling these deposits will be of strategic importance to the Taliban who will prioritise securing these areas and likely encouraging Chinese mining expertise and operations in these areas in return for infrastructure projects. The International Energy Agency estimates that it takes 16 years on average from the discovery of a deposit for a mine to start production, so the Taliban will be keen to pacify and stabilize these regions in order to encourage international development and investment from China and potentially other neighbouring countries.

How will the current situation in Afghanistan impact global terrorism?

It seems almost inevitable that the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan will lead to a changing of the terror threat landscape both locally and globally.

The Taliban takeover has brought with it a number of key factors that are likely to impact both the capability and intent of terrorist groups - whether in terms of numbers, freedom of action, morale, weapons or anything else - and consequently impact on the overall threat of terrorism as a result. This section will highlight each of these key developments and how they may change the capacity of terrorists to conduct attacks both regionally and across the globe.

Taliban freed prisoners in Afghanistan

The reality is that Al Qaeda is in 15 provinces in Afghanistan. IS-KP has aspirations outside of Afghanistan.

- General Jack Keane, Former Vice Chief of Staff, US Army

During the final weeks of the Taliban’s successful offensive, they reportedly freed thousands of Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant – Khorasan Province (IS-KP) prisoners; also among those detainees freed were senior Al Qaeda operatives and Taliban fighters. Pentagon spokesman John Kirby has stated, ‘I don't know the exact number [of freed militants]. Clearly, it's in the thousands when you consider both prisons, because both of them were taken over by the Taliban and emptied’.

Despite IS-KP being enemies of the Taliban, who likely have witnessed Islamic State’s growth worldwide and view them as a threat to the Taliban’s authority in Afghanistan, the Taliban likely saw IS-KP as being useful combatants to join the fight against NATO forces and the Afghan Government, although they did subsequently execute IS-KP’s former leader, Abu Omar Khorasani, and eight other militants, upon entering Kabul. Within a fortnight of the prisoners being released, IS-KP claimed responsibility for the attack at Kabul Airport that killed 13 US service personnel and 170 other people.

This increase in extremist numbers will have an impact on the capability of terrorist groups in the country and the region, not only in terms of people to conduct attacks but also the associated skills, such as bomb making, intelligence, finances etc. Likewise, with greater numbers of extremists, this also increases the opportunity for conducting attacks - however, because NATO targets have been removed from the country, clashes between Taliban and IS-KP are instead expected, with collateral damage being a certainty. IS-KP will likely want to undermine the Taliban and carve out its own areas of the country from which to operate and grow.

Weapons proliferation risk

Taliban forces have been pictured with a range of US-made weaponry and vehicles, seized from the Afghan military.

Much has been made of the increase in Taliban capability that these will bring, but they are also assets which the group can use to fund themselves through black market sales to militant groups or regional powers, especially as they face a bankrupt economy. Although the US are looking at options, which include using airstrikes to target the larger pieces of equipment when spotted, the smaller equipment will be easily smuggled and sold, which could supplement terror groups, like small arms and night vision goggles. Suddenly certain terrorist groups in the region will potentially have access to equipment that is better than the security forces of the country in which they are operating.

Consequently, capability of terror groups in the region and likely further afield will be improved through this weapons proliferation. Considering how far weapons can travel via the black market, there is the possibility that some of these weapons will end up in the hands of organised crime groups, extremists and terrorists in Europe.

Return of a breeding ground for terrorism

There is no doubt that the Taliban’s success in Afghanistan is being celebrated by extreme Islamist groups, violent groups, across the Islamic world and that raises the risk of them being inspired to more violence in Western countries as well as in the Islamic world to further their aims. There is no doubt that the terrorist groups will now feel that they can move to Afghanistan and have some operating space there so the picture could change.

- Sir John Sawers, Former Head of MI6

The original invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 occurred because the country had become a sanctuary for groups like Al Qaeda, perpetrators of the September 11th attacks. Fast forward 20 years and what has changed? The Taliban are back in charge, Al Qaeda still exists and have ties to the Taliban, a new group called Islamic State also has a presence in the country and the US and NATO forces have been defeated spectacularly. Although the Taliban will now wish to return to isolation from the rest of the world, considering it has freed thousands of extremists from prison, it will now have to either deal with them, or live with them. Part of this living with them could be through allowing them to operate in Afghanistan, as long as they don’t threaten Taliban dominance of the country.

Another aspect of this issue is that these terrorists are bargaining chips for the Taliban to use when dealing with regional powers. Countries like Iran, China, Pakistan and Russia do not want to see a breeding ground for terrorism on their doorstep. Russia only in July foiled an Islamic State attack in Moscow. China has used its fight against the Uyghur-separatist Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP), which once operated in Afghanistan as a pretext to repress its Muslim Uyghur minority. Iran is concerned with new movements of refugees, the continual flow of opium across its border, which has been a source of funding for the Taliban, and anti-Iran groups like the Balochis that can use Afghanistan to attack Iran. For the Taliban it can use this threat of it becoming a failed state and therefore a breeding ground for terrorism to extract aid and support from regional countries.

For the US, Leon Panetta, former former defense secretary and CIA director under Barack Obama has stated that the US might have to go back into Afghanistan to take out the Islamic State. The White House has pointed to the US military’s “over-the-horizon capacity” – meaning its ability to hit targets from bases outside Afghanistan. However, if a 20 year campaign conducted in the country could not eradicate the threat of terrorism in Afghanistan, this over-the-horizon capacity is highly unlikely to achieve a better outcome. Although some analysts are predicting that after 20 years the Taliban have learned some lessons and that, knowing the consequences, they are unlikely to repeat their support for groups like Al Qaeda, the group must also be wondering the true likelihood of the West or any other power risking an invasion of Afghanistan again.

Overall, it seems highly likely that Afghanistan will once again become a breeding ground for extremism and terrorism, especially once any economic and education advancements have been rolled back. Such a scenario would mean the capability of terrorists will improve, because they will have a free hand to operate and train, unlike in places like Syria and Iraq, where they are regularly targeted by security forces and airstrikes. Although initially this capability will be felt regionally, that will eventually spread with attacks globally. Intent will also be impacted by this development, as a breeding ground creates more highly trained extremists, who can then use those skills to create opportunities to conduct terrorist attacks.

Refugee crisis

There is likely going to be a mass refugee crisis which will impact anywhere where Afghans can travel to. This will have an impact on the security and stability of the countries which accept the refugees. In Iran, for example, which already has a struggling economy, the arrival of refugees will place greater strain on the jobs market and economy. In Poland, the government has asked the president to declare a state of emergency in two regions of its border with Belarus, which have seen hundreds of irregular crossings. Poland has begun to build a barbed wire fence to curb the flow of asylum seekers from countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan crossing from Belarus.

Historically, in Europe, asylum seekers have been linked to spikes in crime, which has then caused reactionary movements in these countries, and can lead to right wing terrorism incidents. In Copenhagen in 2007, for example, two men, one a Danish citizen born in Pakistan and the other an Afghan citizen living in Denmark were sentenced to twelve and seven years in prison, respectively, for planning a terrorist attack. The prosecution alleged that the men had been in contact with al-Qaeda and that one of them had been at a training camp in Waziristan. More recently, in July 2016, a 17-year-old Afghan asylum seeker attacked passengers on a train in Würzburg, Germany, with an axe and a knife. The attacker was killed by police. Europol classified the attack as jihadist terrorism. In August 2018, in Amsterdam, a 19-year-old Afghan male asylum seeker stabbed and injured two Americans in Amsterdam Central station. The attacker was then shot by a police officer. Europol classified the attack as jihadist terrorism.

Terrorists like those described above could use the refugee flows as cover to gain access to regions like Europe in order to conduct attacks. This will likely have a big impact on the intent to conduct terrorist attacks going forward, especially the opportunity. By using a refugee crisis as camouflage to move into target areas, terrorists could cause a new wave of attacks in the coming months, both regionally and globally.

Propaganda victory

I think there are two problems - I think there is more operating space more likely to be available to groups like al Qaeda, and there have been reports of Islamic State elements present in Afghanistan. If they get the opportunity to put down infrastructure to train and to operate then that will pose a threat to the West more widely. There's also the psychological effect of the inspiration that some people will draw from the failure of Western power in Afghanistan. So, I think, in practical terms and in terms of ungoverned space, but also in psychological terms, it probably does mean an increase in threat over the coming months and years.

- Lord Jonathan Evans, Former Head of MI5

Jihadists are celebrating this as their greatest victory since the September 11th attacks. The US and NATO, who quickly removed the Taliban from power back in 2001, have effectively been slowly beaten over two decades at the cost of thousands of deaths and injuries and multiple billions of dollars. This success will likely be seen as inspiration for jihadist groups around the world and shows that high tech militaries can be beaten with patience and resolve.

In addition to providing inspiration, it will also cause deflation amongst NATO. NATO countries must be asking themselves, after 20 years of military and nation building, how did Afghanistan fall so rapidly, and what interventions can be conducted successfully going forward.

Soldiers and officers who took part in the Afghanistan Conflict will also be asking questions of the politicians and senior military leaders who are responsible for this failure. This comes at a time when there is already massive discontent in the West and will only likely exacerbate the issue.

This propaganda victory will have a large impact on intent, globally. Jihadists around the world are likely to be emboldened and their will to conduct attacks will likely increase, as they attempt to further prove that Western governments are unreliable and vulnerable partners.

Built on military foundations, we implement methodologies that guarantee quality, integrity and context. To better understand the data and principles behind our analysis or to take a closer look at the only multi-domain intelligence solution covering land, sea, air, cyber and space, speak to a member of the Intelligence Fusion team.