The increasingly violent insurgency in West Papua

The pro-independence insurgency in West Papua is becoming more violent and sophisticated at the same time that mining interests and foreign investments are increasing. We provide an overview of the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB), their evolving tactics and targets, and how safe West Papua is to operate in.

Resistance to Indonesian rule in West Papua dates to before its annexation in 1969 when, following a sham referendum, Jakarta formally laid claim to the former Dutch colony. The Organisasi Papua Merdeka or Free Papua Movement (OPM) forms the backbone of the pro-independence movement, which has campaigned unsuccessfully for years for a referendum and independence for West Papua, whose native population differs from that of Western Indonesians in ethnicity, culture and religion.

The militant wing of Papuan independence is dominated by the Tentara Pembebasan Nasional Papua Barat or West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB). For years it has staged attacks against Indonesian rule using guerilla and terrorist tactics; targeting security forces, non-Papuan Indonesians, foreign workers and infrastructure. It was however hampered by a lack of funding, arms and – seemingly – unity. Until recently their campaign was sufficiently disparate and lacking momentum that it could be largely ignored by the government while security forces made a profitable business protecting the lucrative foreign mineral extraction operations on the island.

However, the number of insurgent incidents began to climb from 11 in 2010 to 52 in 2017, and the December 2018 massacre of labourers working on the Trans-Papua Highway by a group of TPNPB led by Egianus Kogoya (see below) marked the beginning of an increase of TPNPB activity notable for its violence and sophistication.

Increase in violence in West Papua

Prior to 2018 the pro-independence movement in Papua did not pose a significant enough threat to be a major concern to the Indonesian government. While foreign workers had been shot dead in suspicious circumstances when travelling near the Grasberg mine in 2002 and 2009, armed resistance was sporadic and opportunistic.

In January 2018 the leader of the TPNPB – Lekagak Telenggen – declared war and called on leaders of the resistance movement’s regional commands to fight against the presence of foreign companies seen to be exploiting the land and its people. The years since have seen an increase in the TPNPB’s operations in terms of violence, tempo and sophistication. It has also seen clashes – previously largely confined to the rugged Central Highlands areas of Puncak Jaya, Lanny Jaya and Mimika – expand to areas traditionally less effected by the insurgency, like Pegunungan Bintang, Intan Jaya, Yahukimo, Deiyai and Keerom.

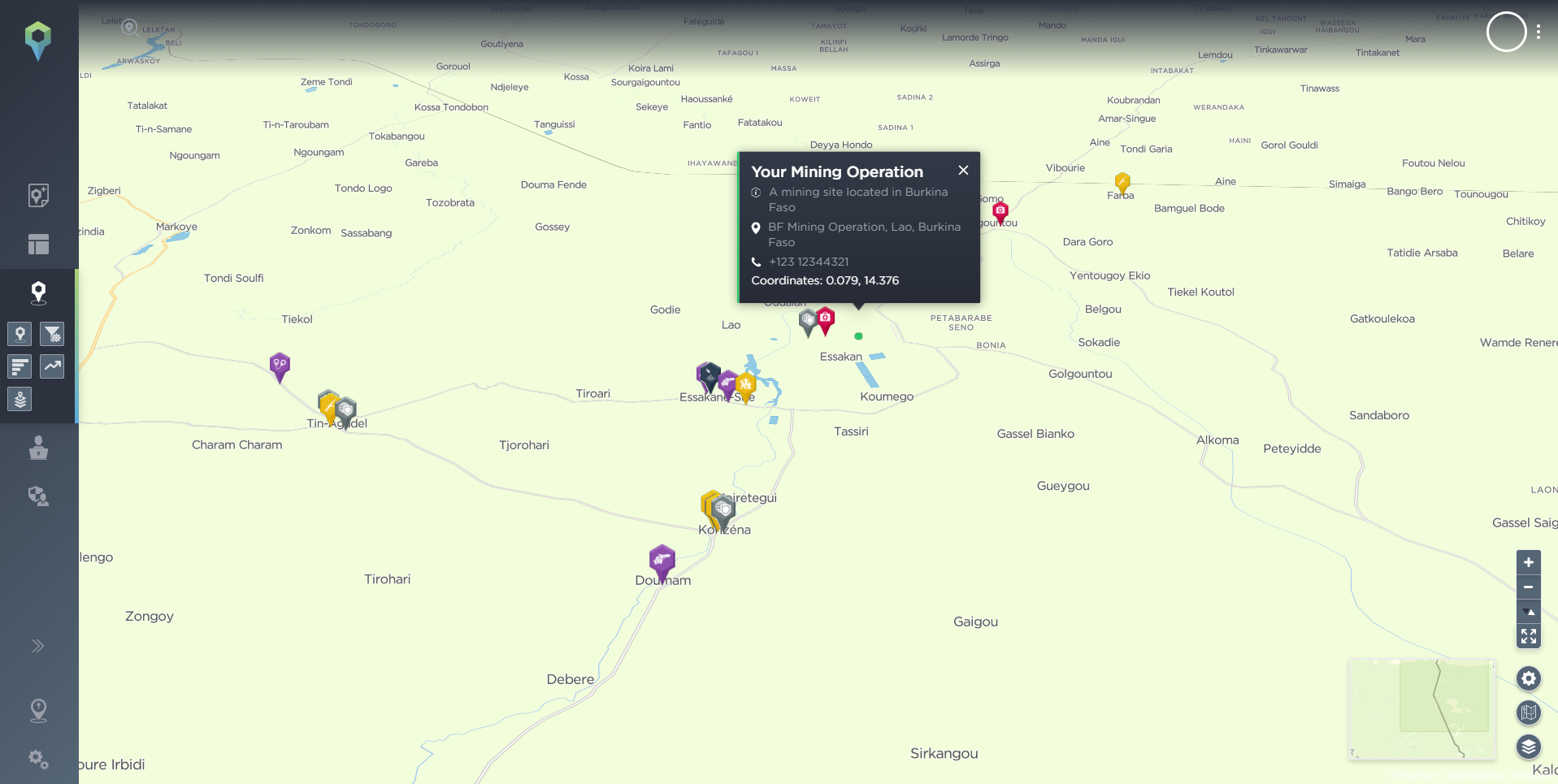

TPNPB/KKB Activity in West Papua, 2023 [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

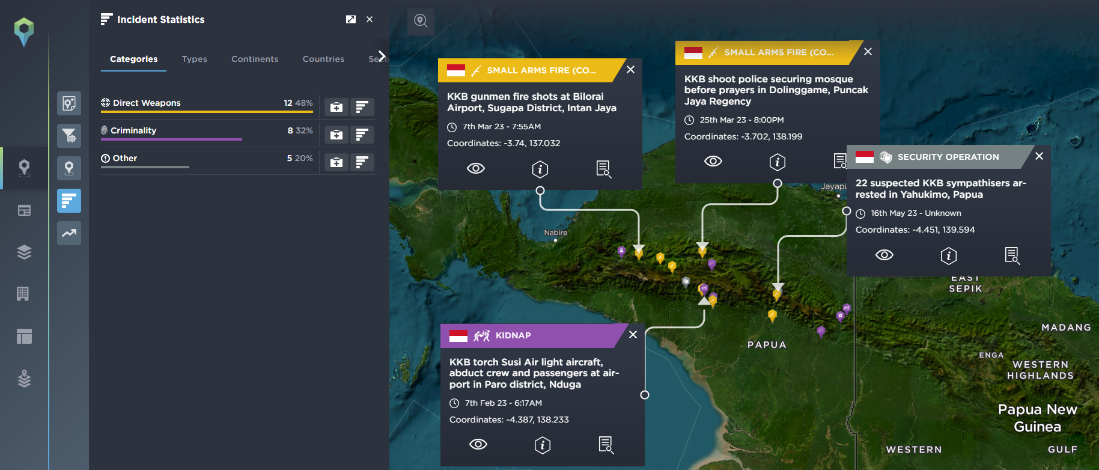

Attacks have also become more ambitious and sophisticated . In June 2020 groups led by TPNPB commanders Sabinus Waker and Undius Kogoya attacked security forces in Intan Jaya before ambushing a well-escorted government fact-finding team in October. In June 2021 Telenggen’s own group temporarily occupied Ilaga airport and damaged infrastructure, while in January 2022 two troops moonlighting as security for a sand mining company were killed by the TPNPB, who then lay in wait and ambushed the evacuations team, killing a third soldier.

The TPNPB has shown evidence of a high degree of tactical competence when carrying out classic guerilla activities. While their attacks include simple arson attacks, sabotage and extortion of businesses, they have also targeted infrastructure in remote areas, kidnapped or killed workers and even assassinated a regional intelligence chief – this last incident leading to the OPM being designated a terrorist group by the Indonesian government. As the January 2022 incident and subsequent attacks have shown, the TPNPB are adept at provoking a security response that leads to a second attack or ambush.

Some notable TPNPB/KKB Activity in West Papua, 2021-22 [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

In February TPNPB under the young and violent commander Egianus Kogoya – whose father was also an insurgent and was killed by the Indonesian army – kidnapped Philip Mehrtens, a pilot for Susi Air, when he landed at a remote airstrip in Paro, Nduga. Efforts to free Mehrtens have so far failed, with a search and rescue team being ambushed in mid-April, resulting in the deaths of five soldiers. What is more interesting is that Mehrtens had flown to the area to evacuate 15 construction workers that were being threatened by the TPNPB, implying that the kidnap of a foreign national could have been the intended goal from the beginning. The fact that TPNPB were waiting at the airstrip strongly implies that they had predicted the course events would take once they threatened the workers.

Additional strengths for the insurgency

As well as having a more unifying leadership providing direction, the approximately 500-strong TPNPB appears to have benefited from an increase in funding and access to weapons. Raids on government outposts are thought to have provided most of the TPNPB’s firearms, but the extremely high profit margins weapons provide in West Papua makes the potential payday too attractive for corrupt security personnel to entirely prevent their illegitimate sale. Smuggling overland from Papua New Guinea and overseas from places like Bougainville are another source of arms.

The TPNPB funds these sales through a combination of kidnap for ransom, extortion and exploitation of local businesses, and donations from local officials, who in some cases may redirect official funds towards the pro-independence movement.

While recent years have seen the TPNPB expand its area of operations, in classic insurgent style it still benefits from the restrictive terrain of West Papua, where the jungles and mountains of the Central Highlands provide a safe haven from government counterinsurgency efforts. The TPNPB also seem to take steps not to alienate the indigenous Melanesian population, often releasing Papuan workers while killing or ransoming Western Indonesian or foreign captives.

Indonesian counterinsurgency in West Papua

The government’s attempts to counter this increased TPNPB activity have been heavy-handed, reactive and largely ineffective. The government is thought to have approximately 35,000 security personnel in West Papua, including from the Indonesian army (TNI), police and paramilitary units such as the Mobile Brigade Corps (BRIMOB). These forces are concentrated primarily on population centres and important commercial sites such as the Grasberg copper and gold mine in Puncak Jaya.

This approach means security forces lack the presence in remote areas needed for effective counterinsurgency or protection of infrastructure workers, leading to a reliance on airstrikes to attack insurgents.

Security forces also make the classic counterinsurgency mistake of rotating forces through a region on short 3–6-month cycles. These “non-organic” units of non-Papuans are regarded as colonisers by many Papuans and have a poor human rights record, with numerous incidents of violence against civilians, from the murder of community figures to the commandeering of local facilities at the expense of the population. This behaviour has been met with a severe lack of accountability and undermined whatever trust many Papuans may have ever had in the government.

The government’s standard reaction of increasing troop numbers to appear strong after an attack is ineffective if not counterproductive. Despite surging the security presence to 3,000 soldiers and police, the March 2020 attack on the Kuala Kencana area of Mimika saw dozens of TPNPB fighters outmanoeuvre these forces and escape with few casualties.

Since 2018 the West Papuan insurgency has grown in strength, sophistication and violence. More coordinated leadership and more weapons have allowed them to stage more frequent and violent attacks targeting infrastructure and commercial interests with brutal but cunning tactics. They have been aided in this by an inflexible and reactive counterinsurgency policy from the Indonesian government that serves more to alienate the local population from the authorities than separate the insurgents from the population. Recent high-profile successes like the kidnap of Philip Mehrtens will likely be repeated in the future, further raising the kidnap threat in remote regions.

The military claims to be trying a different approach, but the increase of coal mining interests in West Papua will provide more targets for insurgents and no doubt lead to further troop deployments. Likewise, the establishment of new administrative provinces in West Papua despite local opposition has served to further alienate the Papuan population. With more weapons, more businesses seen as exploiting the land, and more contentious policies, the insurgency in West Papua can only be expected to gain momentum.

As the situation in West Papua continues to evolve, Intelligence Fusion will be monitoring and tracking any developments as part of our 24/7 intelligence collection. This intelligence gathering is guided by the needs and interests of our clients; as part of your onboarding process we carry out an Intelligence Collection Plan (ICP) so we can understand what is of particular importance to you, your team, and your operations, providing focus to our efforts in addition to our regular intelligence collection.

As a result of our intelligence gathering, we now have a database of more than 1,000,000 incidents, with thousands more mapped every week – each one evaluated and verified by one of our trained in-house intelligence analysts – and presented on our cutting edge threat intelligence platform. If you’d like to learn more about how we do things and how we can help you, get in touch with a member of the team below.