What’s the economic cost of China’s lockdowns?

After two months of stringent lockdown measures, Shanghai – home to 26 million people and the world’s largest container port – has finally begun to reopen. Despite its medical rationale, China’s zero-COVID policy is largely politically driven and closely associated with President Xi Jinping.

Because of the economic harm already inflicted on China, any changes to the policy now could be seen as an admission of error and dangerous for the population, undermining Xi Jinping’s standing ahead of the 20th Party Congress where confirmation of his presumed third term as President and General Secretary is expected.

In light of this, we should not assume that the opening of Shanghai means an end to lockdown disruptions in China. While Shanghai’s global importance focused attention, 50 other Chinese cities with 350 million people have also been locked down, and while these too are opening up they all remain subject to mass testing with sudden and wide-ranging quarantine measures, often at the first signs of an Omicron outbreak.

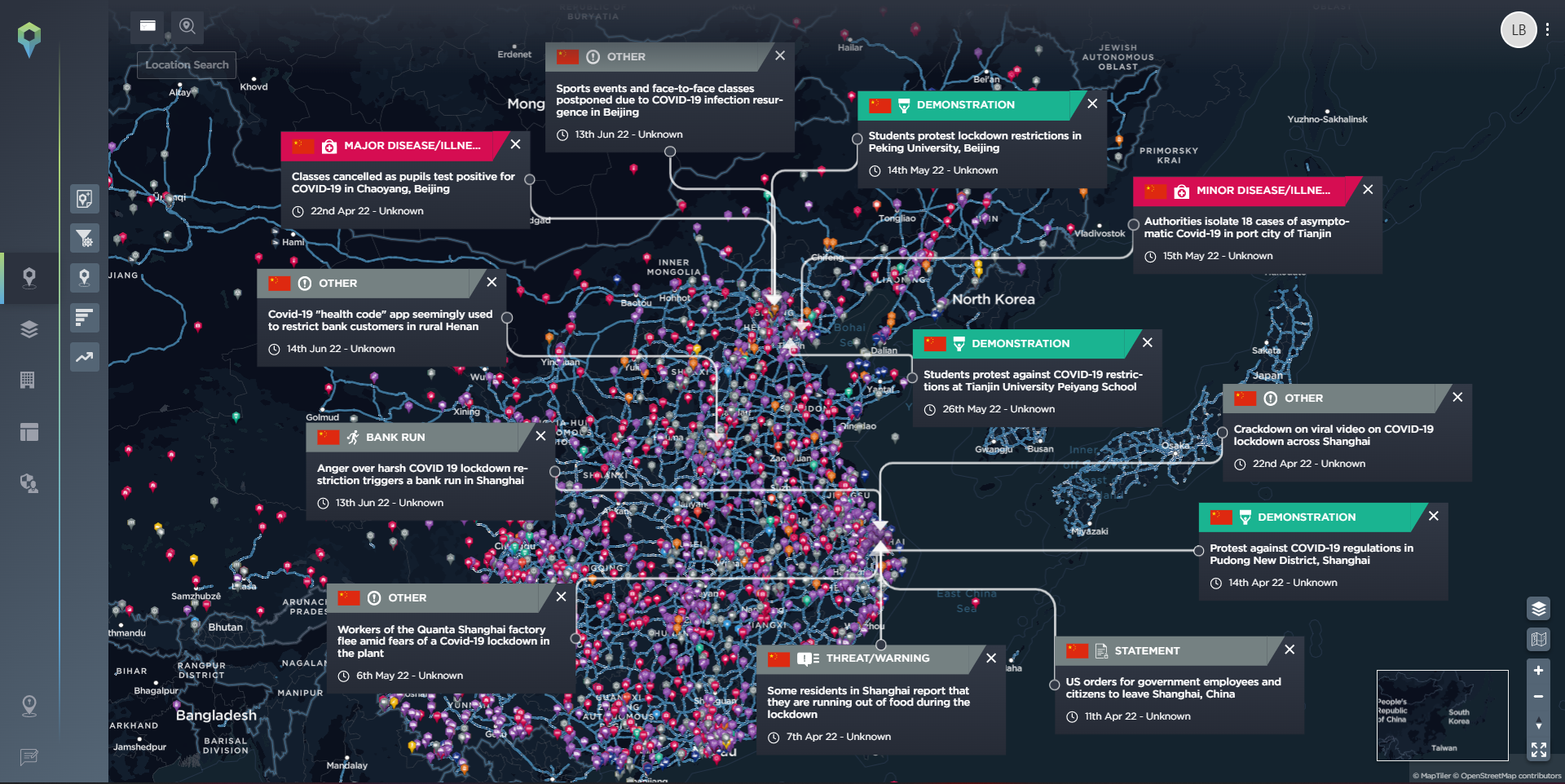

The image highlights a selection of recent COVID-19-related incidents which have been reported across China. [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

Why won't lifting of COVID restrictions prevent logistical chaos?

The easing of COVID restrictions, particularly in Shanghai, will have a significant bearing on global logistics. Wait times for ships at Shanghai port are back to near-normal levels from their peak in April – in part thanks to reduced shipping traffic during the COVID lockdown – and trucking and rail movements are already gradually improving. However, this may not mean an easing in global shipping and supply chain woes.

One of the many legacies of the COVID-19 pandemic is a huge imbalance in the supply of shipping containers, with Europe and particularly Asia suffering acute shortages while empty containers languish stateside. Adding to this a fresh surge of trans-Pacific freight is now expected to arrive in Western ports, particularly the West coast of the U.S., in July and August, just as U.S. port worker unions are engaged in major contract negotiations before the mid-terms in November.

On top of port congestion, container and truck driver shortages, industrial actions and negotiations in the transport sector taking place from the U.S. to Germany to South Korea, shipping prices are likely to remain high. How much of these costs can be absorbed by companies or passed on to the customer during a climate of high inflation and cost of living increases remains to be seen, but with global oil prices painfully high and without signs of dropping, consumers are likely to see further shortages and inflation for some time until supply chains can normalise.

How will China's lockdown impact the global economy?

The effects of China’s lockdown policies on its economy are likely to be severe. Even if China continues to ease restrictions and manufacturing gets back on track – which is not at all certain given the continued zero-COVID policies of the government – hopes for a fast recovery seem slim. In March the National People’s Congress (NPC) announced an annual growth target of around 5.5% (slightly below 2019 figures), although how China will achieve this even with stimulus measures being rolled out is debatable.

Like many countries, the headwinds facing the Chinese economy are numerous. The bloated property sector, which has been the source of so much GDP growth for decades and saw contractions in late 2021, has suffered further during the lockdowns from reduced sales. Government crackdowns on the country’s tech giants have spooked investors and the shock the pandemic – amongst other political factors such as trade tariffs and pushback over the treatment of Uyghurs – has had on global supply chains has spurred some prominent large multinationals to reevaluate their China-based operations. An export-led recovery also seems unlikely as logistics chains continue to be disrupted and rich consumers in the West reduce spending as they struggle with inflation and the cost of living. Domestic consumption will also likely remain low due to rising unemployment and continued lockdowns hurting retail and services.

Little or no Chinese growth will have a hugely detrimental effect on the global economy as it struggles to recover from the pandemic and the ongoing issues caused by the war in Ukraine. For years China has been the engine of global growth, and a great deal of global economic sentiment assumes robust Chinese growth, which was predicted to account for 1/5th of global GDP growth until 2026. Such is the severity of some estimates that Yale economist and former Morgan Stanley Asia chairman Stephen Roach commented “The resilience of China, or the China cushion … was the only thing that stood between a weak post-GFC [Global Financial Crisis] recovery and relapse back into global recession during that earlier period. Fast-forward to today: The cushion has no air in it.”

Are the lockdowns in China politically driven?

The continuation of the apparently unsustainable zero-COVID measures is not regarded as being scientifically driven but rather political. Although China appears to have had great success dealing with the original COVID-19 outbreak, those same measures have proven to be nowhere near as effective against the highly infectious but comparatively mild Omicron variant. Even so, the policy of pursuing zero-COVID has become so closely associated with the infallible technocracy of the CCP and President Xi in particular that it has become impossible to abandon despite the economic and social damage it has done.

This irrational-seeming adherence to a policy despite its damaging outcomes is nothing new to the PRC. Whether the campaigns against sparrows and rats during the Great Leap Forward or the long implementation of the One-Child Policy that resulted in the country’s impending demographic crisis, the PRC has demonstrated not only its resolve to stay the course no matter the consequences, but also its unwillingness to change on a number of occasions. As well as the economic damage there can be no doubt that lockdowns have damaged China’s prestige. As many countries, particularly in the West, have carried out successful vaccination campaigns and moved on to manage the virus as an endemic risk, China’s rigid zero-COVID policy continues to be implemented. Dystopian images of streets patrolled by drones, HAZMAT suit-wearing officials killing pets and the stories of horrendous conditions during the Beijing Olympics all run counter to the CCP’s narrative of competent, efficient and superior rule.

Such is the animus against COVID-19 that the need to contain outbreaks seems to have overturned the long-standing goal for provincial governments of GDP growth no matter what the cost. Local governors now appear to be willing to sabotage their region’s prosperity in order to avoid even the chance of a COVID-19 outbreak, which in the current climate would probably be far worse for their careers than economic contraction. Such decisions send ripples that are felt the world over as restrictions between districts in China are a significant contributing factor to the supply chain disruptions and port congestions, forcing factory workers and truck drivers to run a gauntlet of testing, quarantines and travel restrictions to produce and deliver goods demanded abroad.

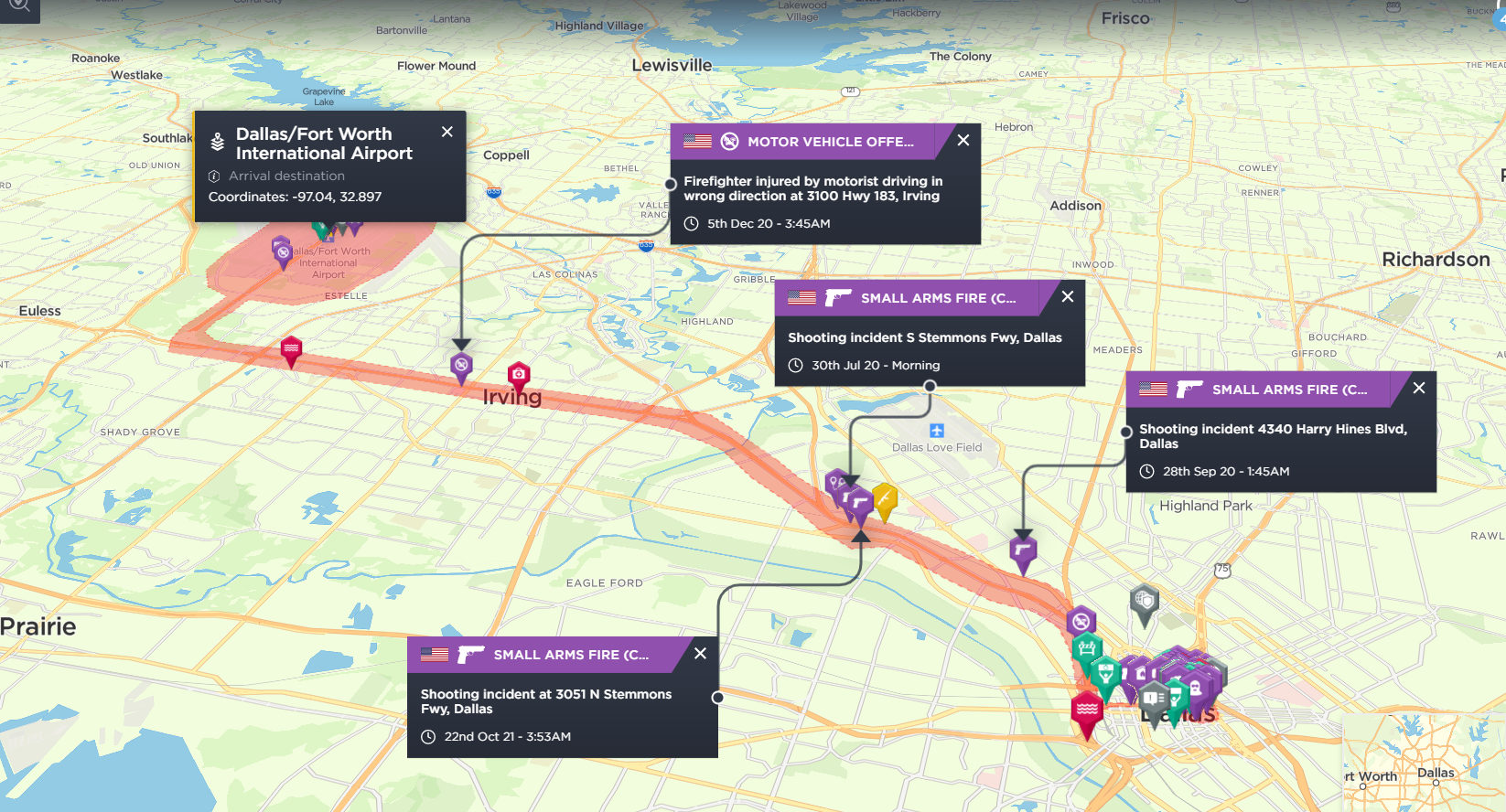

An example of lockdowns that have been reported across China in the last six months. [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

What is China's vaccination rate?

There is however one credible argument in defence of China’s COVID lockdowns – the poor state of the Chinese healthcare system and continued low vaccination rates amongst the vulnerable and elderly population. At the current rate of vaccination, it is estimated it will take until March 2023 for 90% of elderly Chinese to have had three doses of a domestically produced vaccine, giving a reasonable degree of protection from Omicron.

High levels of vaccine hesitancy particularly amongst the elderly and a nationalistic narrative against Western-developed vaccines have not helped the campaign, while government scaremongering over potentially millions of deaths should the outbreak go unchecked has constrained the government’s options to the change policies. Even so, a calculation has clearly been made that to change policy now would risk the lives of too many Chinese and therefore, perhaps more importantly in the eyes of the ruling elite, Party credibility. Although economic prosperity has been a key pillar of this credibility for decades, it would seem to be a price President Xi is willing to pay, in the short term at least.

While Shanghai may be opening up it, like the rest of China, is subject to snap lockdowns of entire sectors at the slightest hint of Omicron. The government’s containment strategy has proven to be damaging and likely inefficient, but also highly unlikely to change.

Indeed, at the time of writing, fresh Omicron cases have led to some restrictions being re-imposed in Beijing and Shanghai. Until this strategy changes, then, we can expect a high risk of more lockdowns, more problems for supply chains, and more economic turmoil until at least 2023.

If you’d like to take a closer look at the data that supports our analysis, schedule a demonstration of our threat intelligence platform. Providing timely, accurate incident data to security teams across the world, we can help you to better protect your people, assets and operations in times of uncertainty.