The Risk of Renewed Civil Unrest in Hong Kong

China’s latest assertive move may cause long periods of civil unrest to return to Hong Kong. Intelligence Fusion examine the risk that Beijing’s security legislation and its expected backlash pose to businesses and organisations operating in Hong Kong.

Recent Developments

Beijing has proposed new security legislation to Hong Kong, showing that it is determined to go against protesting Hong Kong citizens who demand to retain their territorial autonomy. Beijing’s first draft sets out the principles of the new bill, which will be designed to ban anything the central authorities deem “foreign interference” or “activities that endanger national security”, making it more difficult to organise political opposition against China and potentially also to conduct business operations in Hong Kong.

The fact that new security legislation was proposed does not come as a surprise. As has been stated in Hong Kong’s Basic Law (art. 23), a new piece of security legislation should be introduced as soon as possible to facilitate its return to China. Such a bill had already been introduced in 2003 when major riots caused Hong Kong’s former chief executive Tung Chee-hwa to step down. Similarly, a wave of protests and riots caused a controversial extradition bill to be retracted by Hong Kong’s government in 2019.

What is surprising about this latest piece of legislation is not only that it was proposed when anti-Chinese sentiments are rising high from the COVID-19 outbreak, but also that it was proposed by Beijing and not by Hong Kong’s own government. It signals that the Chinese Communist Party can no longer afford to have civil unrest paralyse the territory, which is of great strategic importance to China.

___________

Recent protests sparked by the new national security legislation have been almost unrecognisable from last year’s demonstrations due to Hong Kong’s COVID-19 countermeasures. Authorities have also cited COVID-19 public gathering restrictions to ban planned protests, such as a recent vigil in Victoria Park on 4th June 2020, which went ahead despite the ban to mark the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre.

___________

After a protracted period of civil unrest in 2019, a large portion of Hong Kong’s businesses now support measures to quell the city’s protest movement, hoping that Beijing’s new laws will help Hong Kong to stabilise and recover economically. Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement, on the other hand, has strongly opposed China’s latest proposal and quickly organised new protests throughout the city. They quickly gained support from many Western governments, who warned that the new legislation could erode Hong Kong’s autonomy under the one-country, two-systems principle.

As a result, the British government suggested it would ease immigration rules for citizens of its former colony and the U.S. administration even went as far as announcing to end Hong Kong’s preferential trade and travel status. If the U.S. Congress agrees to withdraw Hong Kong’s privileges, the territory will eventually become subject to the same tariffs as China, which is in an ongoing trade dispute with the U.S. Besides trade regulations, this would also affect shipping access and aviation rights across the Pacific.

How exactly these successive blows from Beijing and Washington will affect Hong Kong will remain unclear until the new national security law is finalised. What is already clear to see, however, is that Hong Kong will likely experience renewed periods of civil unrest every time Beijing attempts to exert its control over the territory, which will be a gradual process until Hong Kong officially returns to China in 2047.

Security Risks Stemming from Civil Unrest

What can the events of the past year tell us about the risk that returning civil unrest poses to businesses and organisations in Hong Kong post-COVID-19?

On the 9th of June 2019, mass protests broke out in reaction to an attempt by Hong Kong’s government to pass a highly controversial bill which would allow the extradition of criminal suspects to mainland China. Many Hongkongers took to the streets fearing that the bill would be used to target political prisoners and opponents of China. More broadly, it heightened concerns amongst Hong Kong’s population that their civil and political liberties are being gradually eroded as Beijing’s influence in the territory increases.

The protest movement kept up its momentum, even when the controversial bill was eventually withdrawn at the beginning of September. This is because the movement was about much more than just the bill. Ever since the riots in 2003 and the Umbrella Movement of 2014, it has been about the future of Hong Kong’s democracy as a whole. The only reason that protests and civil disobedience came to a temporary halt this time around was due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

___________

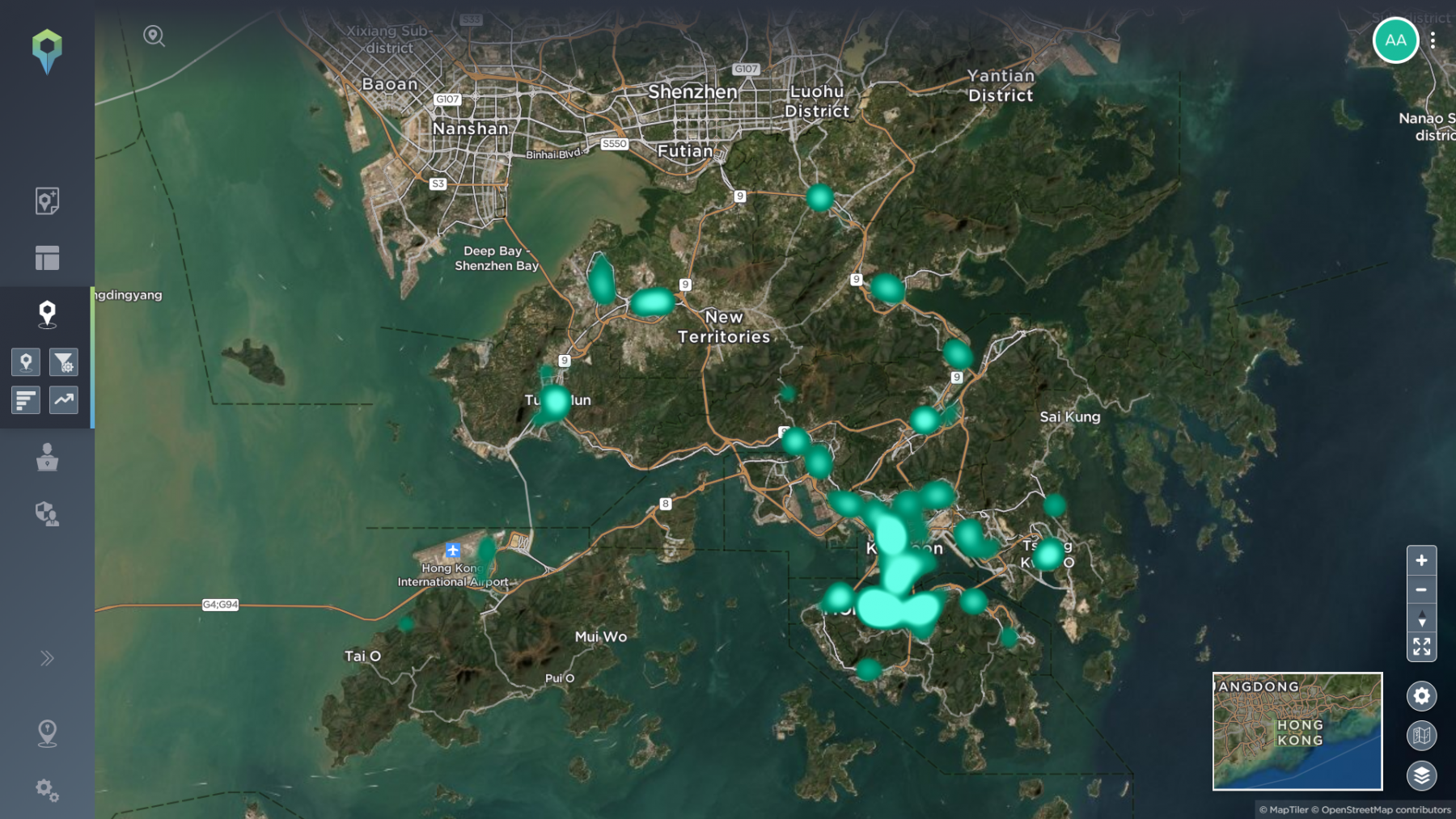

2019 saw civil unrest concentrated around the central areas of Hong Kong Island, where most of the government and administrative buildings are located (Admiralty, Central and Wan Chai). However, incidents of civil unrest were recorded across the territory, from the busy commercial parts of Kowloon to the more quiet residential areas of the New Territories, not to mention the significant disruption caused by protests at the airport on Lanzhou Island.

___________

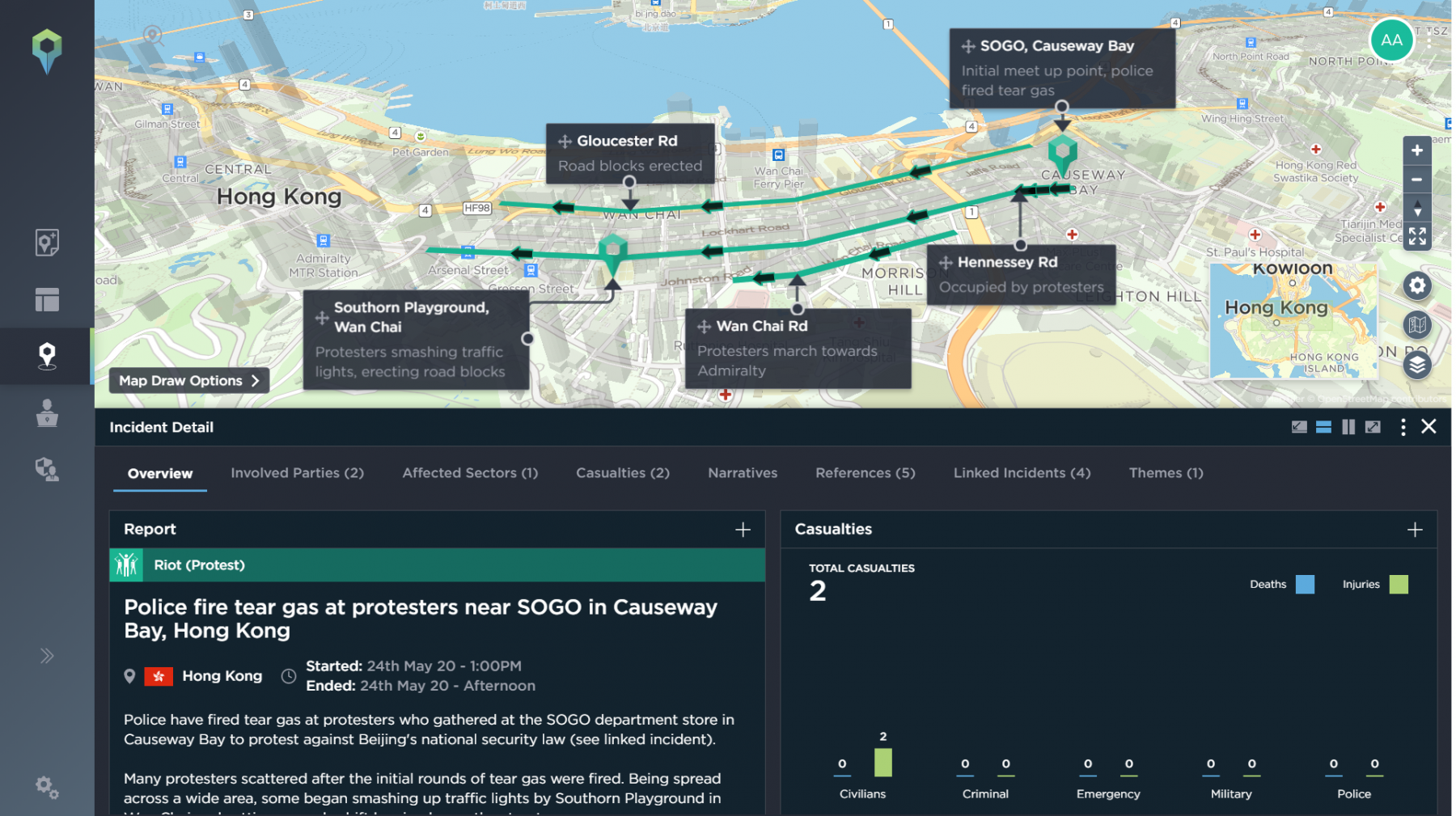

On a tactical level, protesters in Hong Kong have mastered their dense urban environment. By taking advantage of the city’s modern infrastructure and digitally well-connected population, protesters have been able to adopt the tactics of guerrilla warfare and adapt them to modern-day activism. After police disperse initial large scale gatherings, protesters would often retreat by using the city’s efficient subway network, only to pop-up again and stage rallies at multiple new locations. Acts of vandalism would often be committed elsewhere specifically to draw police attention away from gathering sites. By using encrypted messaging tools such as Telegram, protesters would coordinate their movements to outmanoeuvre riot police, frequently quoting Bruce Lee’s advice to be like water.

However, civil unrest in Hong Kong has grown to encompass much more than just marches and rallies. Although the majority of protesters continue to gather peacefully, hard-liners have adopted multiple strategies to cause targeted commercial and economic disruption, hoping that this will put pressure on the local government. For example by blocking access to roads, public transport and the airport, or by targeting private property. Private businesses have been attacked by protesters for saying or doing anything that appears to discredit the pro-democracy movement, often by having their storefronts vandalised or by being boycotted (HSBC, MTR Corp, Maxim Group, Activision Blizzard). In some cases, staff members or their relatives would have their personal details published online in so called ‘doxxing’ incidents (HSBC). Meanwhile, businesses who spoke out in support of the protests have been penalised by Beijing (Cathay Pacific, Zara, Houston Rockets).

Throughout the year, escalating levels of violence have increased risks further. Animosities grew as battles between protesters and police became routine. After some important political concessions from Hong Kong’s government, police brutality and their lack of accountability became the predominant reason for protesters to continue organising. When calls for an independent investigation into police violence fell on deaf ears, protesters resorted to violent forms of retaliation.

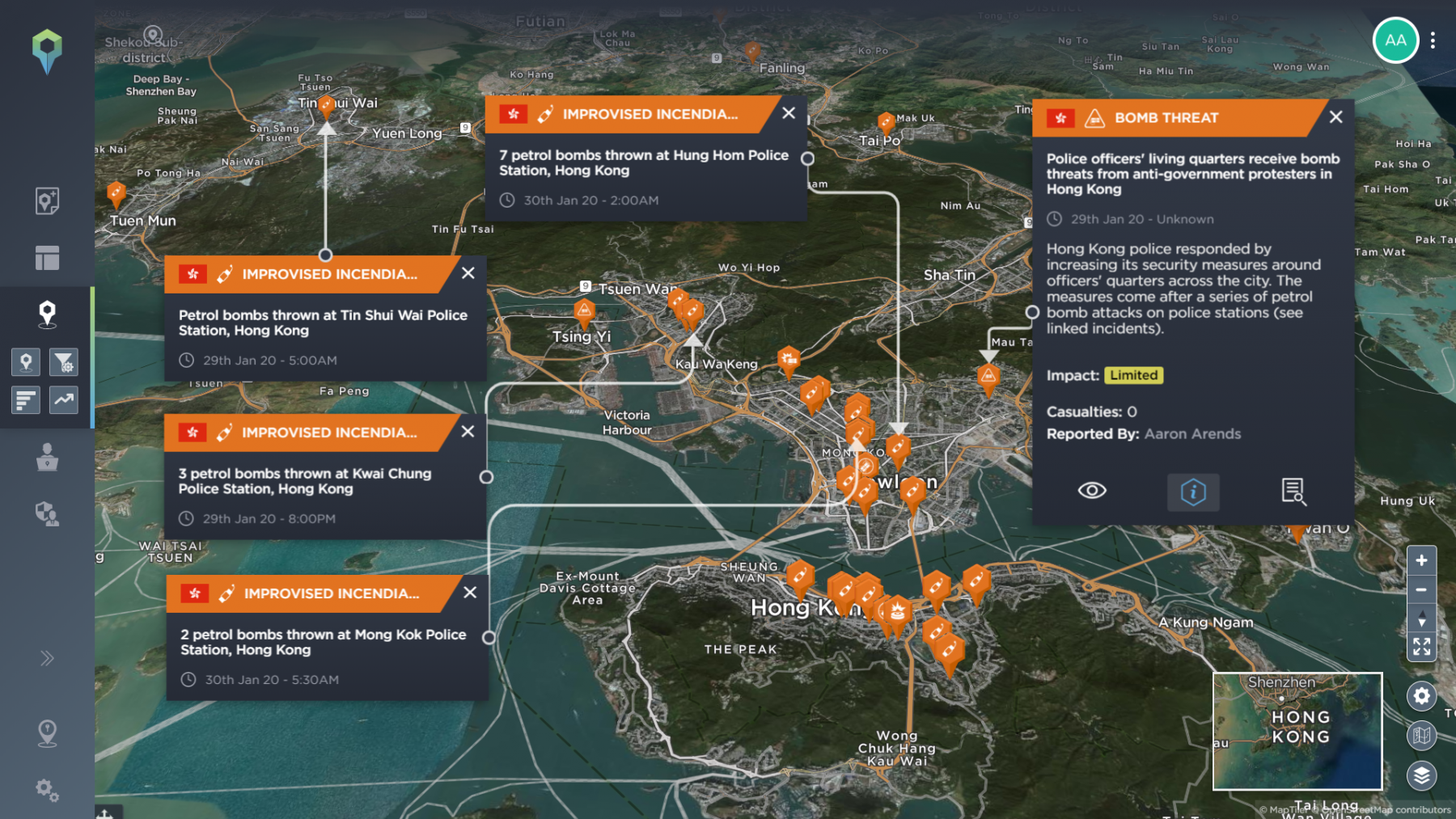

Police frequently received letter bombs and anthrax hoaxes, whilst their premises became vandalised by petrol bombs overnight. Although initial anxieties over the government’s response to COVID-19 saw the bombing campaign expand to include targets such as hospitals and quarantine centres, the hard-liners slowly began to retreat into self-isolation during the spring of 2020.

___________

Petrol bombs have been the preferred offensive tool by hard-liners, whilst most protesters rely on non-violent defensive tools such as laser pens to blind out facial recognition cameras. Protesters have also used umbrellas, traffic cones and leaf blowers to shield crowds from tear gas, tactics that were quickly adopted by the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S. after the death of George Floyd.

___________

A significantly different Hong Kong seems to be emerging from the lockdown. Unprecedented crowds of over a million have turned into a few thousand at most. Since the height of Hong Kong’s resistance, several thousand passionate activists have fled out of fear of prosecution. The latest developments and ongoing Chinese encroachment will likely push more natives to migrate to Taiwan and elsewhere, whilst mainland Chinese authorities are playing the long-game by incentivising Han Chinese to settle in the city, a strategy that has proven to be effective at quelling dissent in both Tibet and Xinjiang. Whether or not apathy eventually sets in amongst the population of Hong Kong, its pro-democracy movement is likely to die a slow but violent death in the coming decades.

Intelligence Fusion will continue to monitor the civil unrest as it evolves across Hong Kong. If you’d like to take a closer look at the intelligence and data that supports analysis like this, we’re offering 14-day free trials to eligible businesses. Request a demonstration of our platform online.