Insurgency in Mozambique: Oil and Gas under threat?

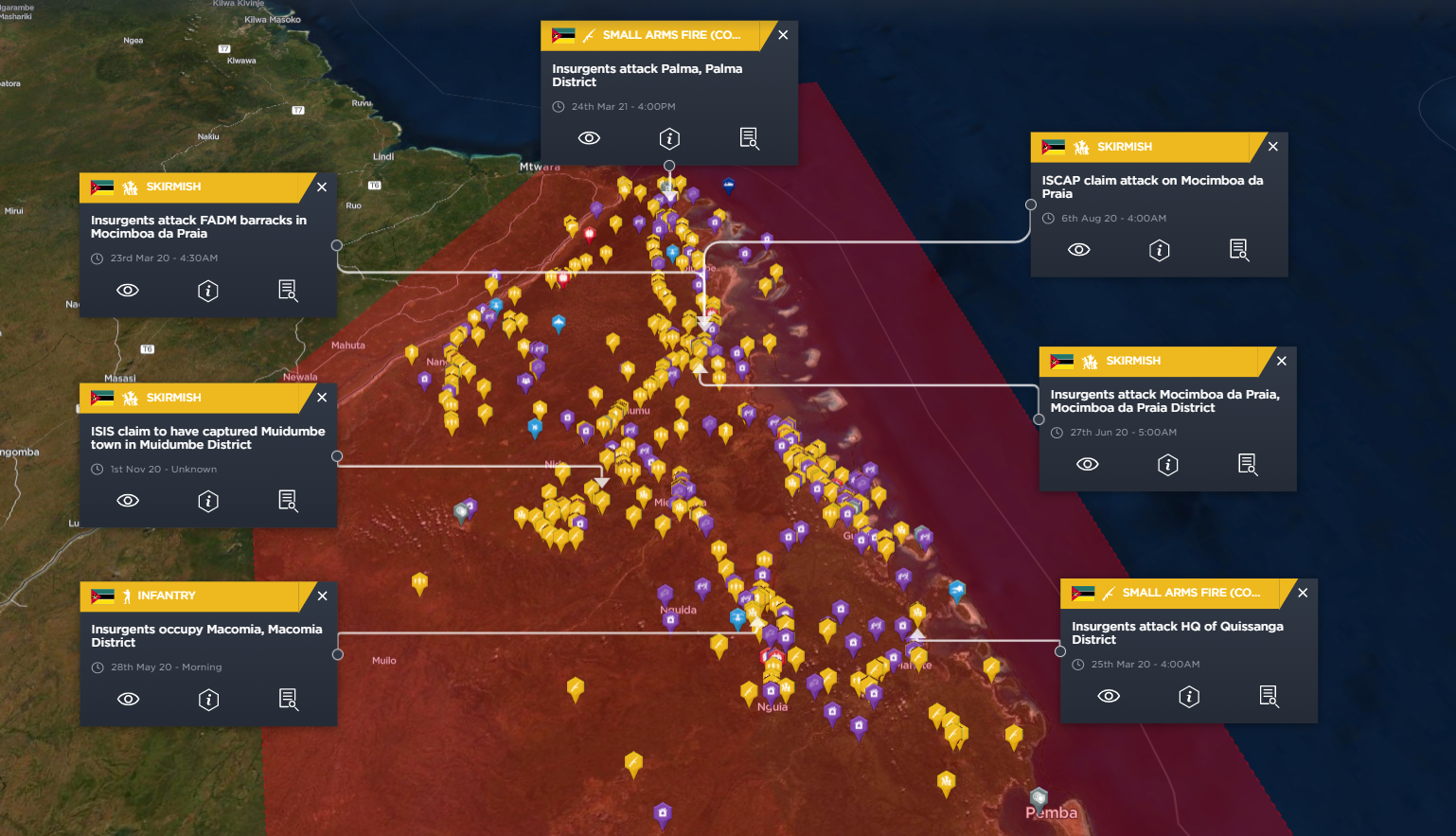

The insurgency in Mozambique hit international headlines in early 2021 following a multi-pronged, well-organised and deadly attack on Palma - just a few kilometres away from one of Mozambique's oil and gas interests at the multi-billion dollar Total Energy site in Afungi. This report will explore the origins, background, tactics, targets and significant activities of the group behind these attacks, and take a look at some possible scenarios going forward, and the threat level presented by the Mozambique insurgency.

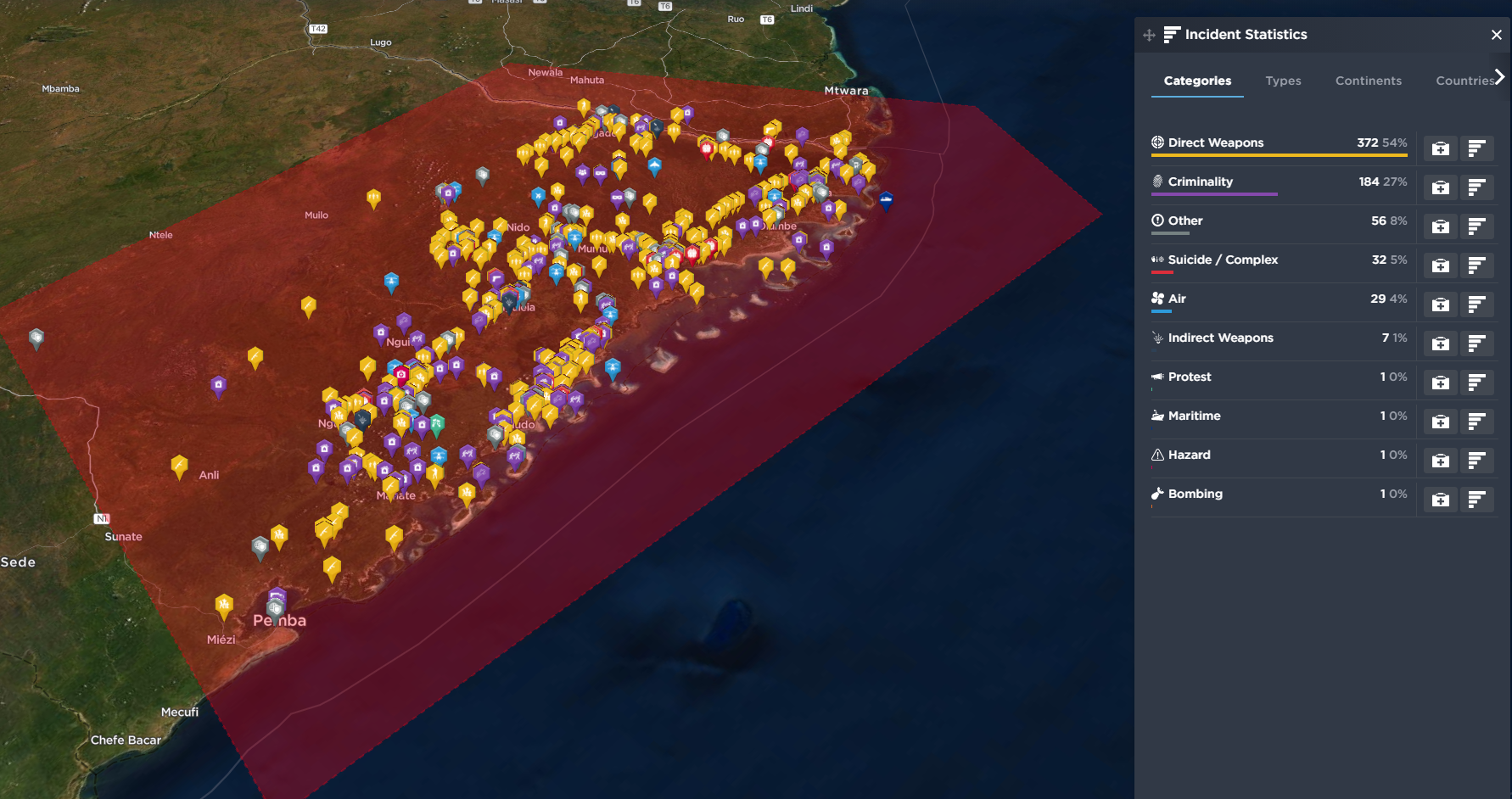

In October 2017, about 30 hooded and armed men carried out three overnight attacks in Mocimboa da Praia District of Cabo Delgado Province in northern Mozambique, the first in a series of escalating attacks in Mozambique’s Islamist insurgency. While most attacks have gone unclaimed, the group behind the attacks is known as Ahlu Sunna wa Jama (ASWJ) or by the local population and by some members of the group, as Al Shabaab (the youth), and since 2019 have also been referred to as part of Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP), a designated Terrorist Organisation by the United States as of March 2021. The degree to which the group can really be seen as ISIS in Mozambique remains a question for now – but the group have at the time of writing conducted at least 552 attacks leaving at least 1,198 civilians dead; and a total of 2,480 people (security forces, civilians and insurgents) have been killed since October 2017 in actions attributed to security forces and ASWJ. Since the start of 2020, ASWJ have conducted more than 300 attacks in Cabo Delgado Province of Mozambique, a significant escalation in the number of attacks and a sign of their growing threat in east and southern Africa. United Nations agencies have warned of a protracted humanitarian crisis as result of the insurgency in northern Mozambique. Close to 700,000 people have been displaced due to the conflict in Cabo Delgado Province.

Brief History

Although ASWJ carried out their first attacks in October 2017, concerns surrounding extremist ideologies taking hold in the region began to grow in the early 2000s. There are reports that the group indoctrinated young children sent by their parents in the 2010s. Local Islamic leaders believe extremist ideologies arrived from Tanzania and Somalia via foreign nationals but also through young Muslims indoctrinated in Wahhabi Islam while studying abroad in Sudan, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. As noted by Eric Morier-Genoud, similar movements to the ASWJ sect have were identified in 1989-90 in Nangade District and later in 2007, when a young man named Sualehe Rafayel of Makua ethnicity returned from Tanzania and attempted to convert members of a mosque in Muape village in Balama District. He is known to have rejected the secular state. According to Morier-Genoud, the Al Shabaab sect began in Chiure district and was founded by a man called Abdul Carimo. Following clashes with police and other local Muslims angry at the sect, Carimo was imprisoned but later escaped. He was recaptured in 2017 and reported to have died in 2018. The sect then expanded across the province.

According to an ISS (Institute of Security Studies) study, the first signs of extremism came to light in 2014 and 2015 in Mocimboa da Praia when young people from local mosques started mosques of their own. The group is reported to have set up at least two mosques in the Nanduadue neighbourhood of Mocimboa da Praia. By the end of 2016, according to research carried out by Morier-Genoud, the Al Shabaab sect was active in Palma, Nangade, Mocimboa da Praia and Montepuez districts of Cabo Delgado province with signs of its presence in Macomia and Quissanga. The sect had also been expelled from Balama, Ancuabe and Chiure districts as Muslim leaders and the state repressed the activities of the group. After violent clashes between authorities and members of the sect, two Kenyan and Tanzanian sect members, who according to the police called for people to reject the existence of the state and called for non-attendance of schools and use bladed instruments for protection, were deported from Mocimboa da Praia.

Research on the group carried out in 2019 found that leaders of the group are both local and foreign, some with informal and formal business networks in Mozambique and Tanzania. They are said to have links with fundamentalist Islamic cells in Tanzania, Kenya, Somalia and the Great Lakes region including with Al Shabaab networks in Somalia and Kenya. Leaders of the group are also reported to have links with the now deceased Kenyan Muslim cleric Aboud Rogo Mohammed (who had links to Al Shabaab in Somalia) and used his material to radicalise youths in Al Shabaab madrassas. In March 2021, the United States named Abu Yasir Hassan, a Tanzanian national, as leader of the group. In early 2018, the police reported that a foreigner of Asian origin was shot dead and that three other foreign nationals were being sought. Between October 2017 and March 2018, the FDS claimed that criminal proceedings had been brought against 370 individuals; among the 370 were 52 Tanzanians, three Ugandans and one Somali. Videos of the group have shown its members speaking in Kiswahili. Arabic is also reported to be spoken by members of the group along with local languages.

President Nyusi has claimed that the government have been tracking the group since 2012 and that they identified Tanzanian Abdul Shakulo as promoting anti-government disobedience, banning children from attending schools and making attendance to madrasas mandatory. The police in 2018 identified Abdul Faizal, Abdul Remane, Abdul Raim, Nuno Remane, Ibn Omar and a sixth known only as Salimo, who they claim are leaders of ASWJ.

Individuals with radical ideologies had been reported to the government and the group’s strict interpretation of Islam was rejected by most mosques in the region, while local authorities began to dismantle mosques where such ideologies were taught, as was reported in late 2017. The group existed in a non-violent form until 2015, when it began to incorporate military cells. According to research carried out by Saide Habibe, Salvador Forquilha and João Pereira after the October 2017 attack, the group finances its activities through donations, received through mobile money transfers such as M-Pesa, and the illicit economy.

Root Causes

The levels of poverty in the northern provinces of Tete, Niassa, Cabo Delgado, Nampula provinces are higher than the southern provinces of Gaza, Inhambane, Maputo. In Cabo Delgado, there are high levels of unemployment and poor service delivery, including healthcare, education, sanitation, electricity and other infrastructure despite the province being rich in natural resources. These conditions along with ethnic divisions borne out of competition for access and control of resources by political elites are all cited as root causes that have contributed to the area’s susceptibility to the penetration of radical religious ideologies and anti-government sentiment. The group is known to reject the authority of the state and its institutions, including schools and courts. ASWJ have also exploited such conditions to recruit. After 2017, many recruits came from the coastal districts of Cabo Delgado and Nampula provinces, joining the group through promises of cash, employment, marriage ties, informal networks of friends, madrassas, mosques, informal trading businesses and community-based Muslim youth associations.

SIGACTS (Significant Activities), trends and tactics

While the size of the group is unknown, it is likely to be between 500 and 1000-strong. According to early reporting, the group is said to be composed of several semi-autonomous cells each with their own leadership but attached to a central command. Cells are also said to have been established in Kibiti, Tanzania. Early claims stating that about 30 to 40 members of the group from various cells had received training from groups operating in the greater south-east region of DRC, and others such as Al-Shabaab in Somalia and Kenya, have not been substantiated, however. Moreover, given that these other groups operate with more sophistication, such as the use of IEDs or suicide bombers, such tactics would likely have been implemented in Cabo Delgado. Earlier reports also claimed that a former expelled police officer planned the October 2017 attack in Mocimboa da Praia and that two former expelled border guards received 25-30,000 meticais (350-420 euros) to provide military training in camps in the region – some in sheltered places in the middle of the bush, others in the backyards of two supposed religious leaders, linked to the armed cells. Reports from a group of 23 women who escaped from ASWJ, revealed that at the group’s bases, children and teenagers were seen undergoing military training and machete fighting with young men eager to fight. The group is also said to be well-organised with access to technology and information. Members of the group come from different social classes, including foreign nationals, with people dedicated to healthcare, telecommunications, filming, mechanics and fighting. The women also reported of tensions within the group.

Targets

The first major attack carried out by the group targeted multiple police stations in Mocimboa da Praia. Civilians were not targeted during this attack. However, they were warned that they would only be targeted if they report the individuals to authorities. Most attacks carried out by the group in 2017 and 2018 involved the use of machetes and knives. They targeted villages/settlements located in isolated/difficult to reach areas as the FDS (defence and security forces) consolidated their positions in larger urban areas.

Trends

The frequency of skirmishes with security forces has increased since 2019. Attacks have also become more audacious and complex with insurgents targeting and controlling territory, such as Mocimboa da Praia town, and launching attacks on multiple villages in Muidumbe District. ASWJ have used squad and platoon sized units for attacks on small settlements and villages, with company sized units used in attacks on towns.

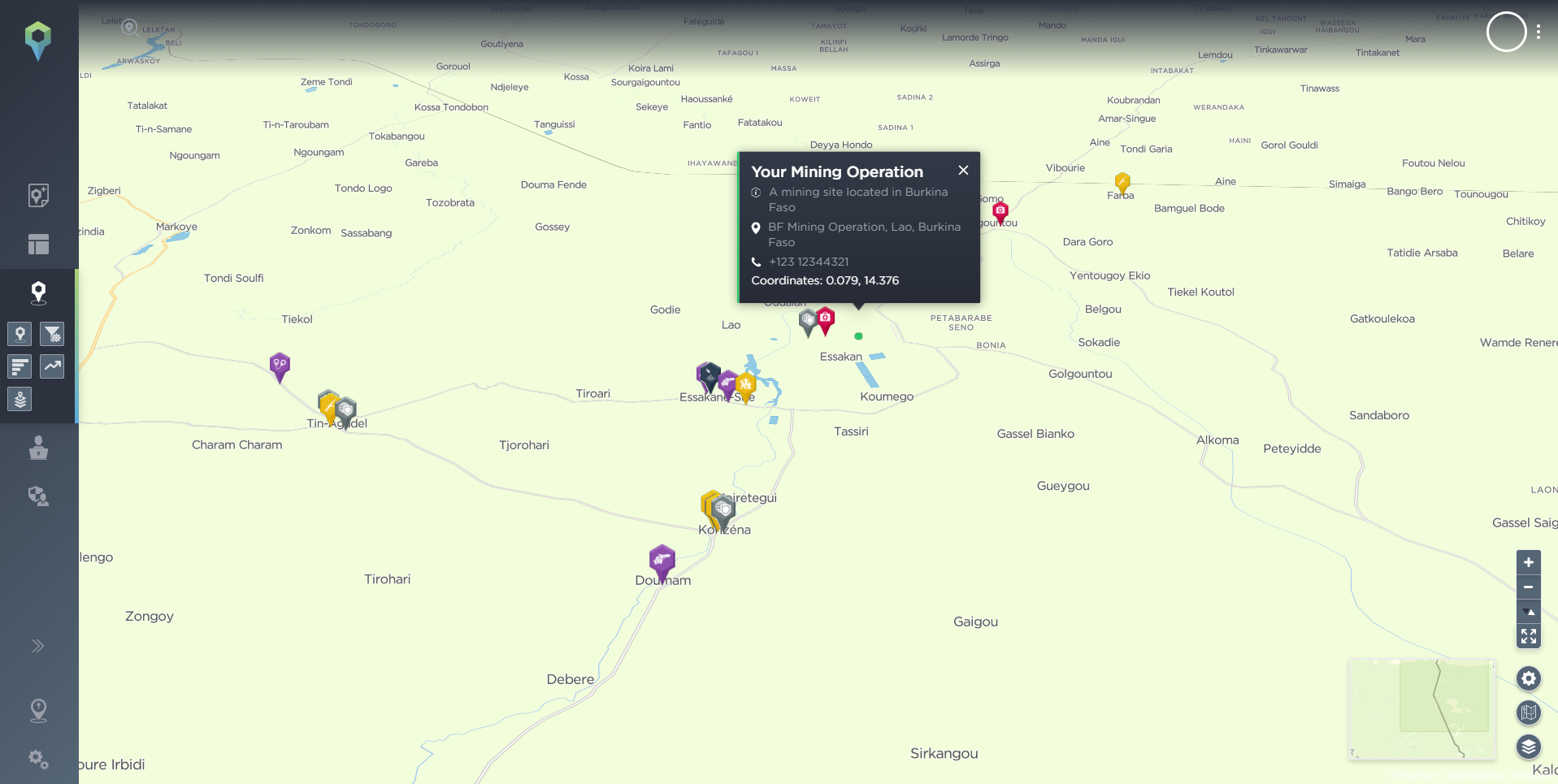

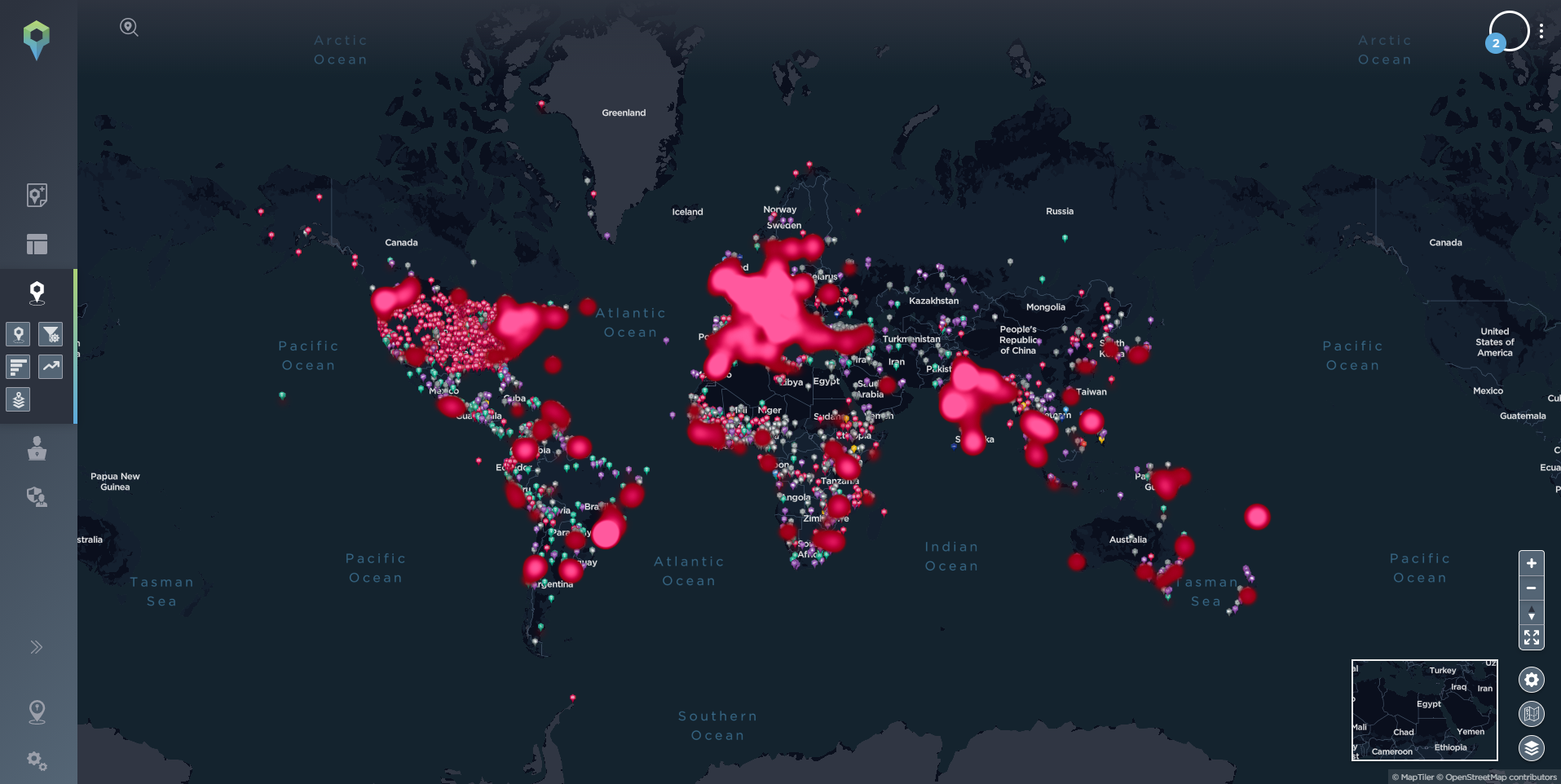

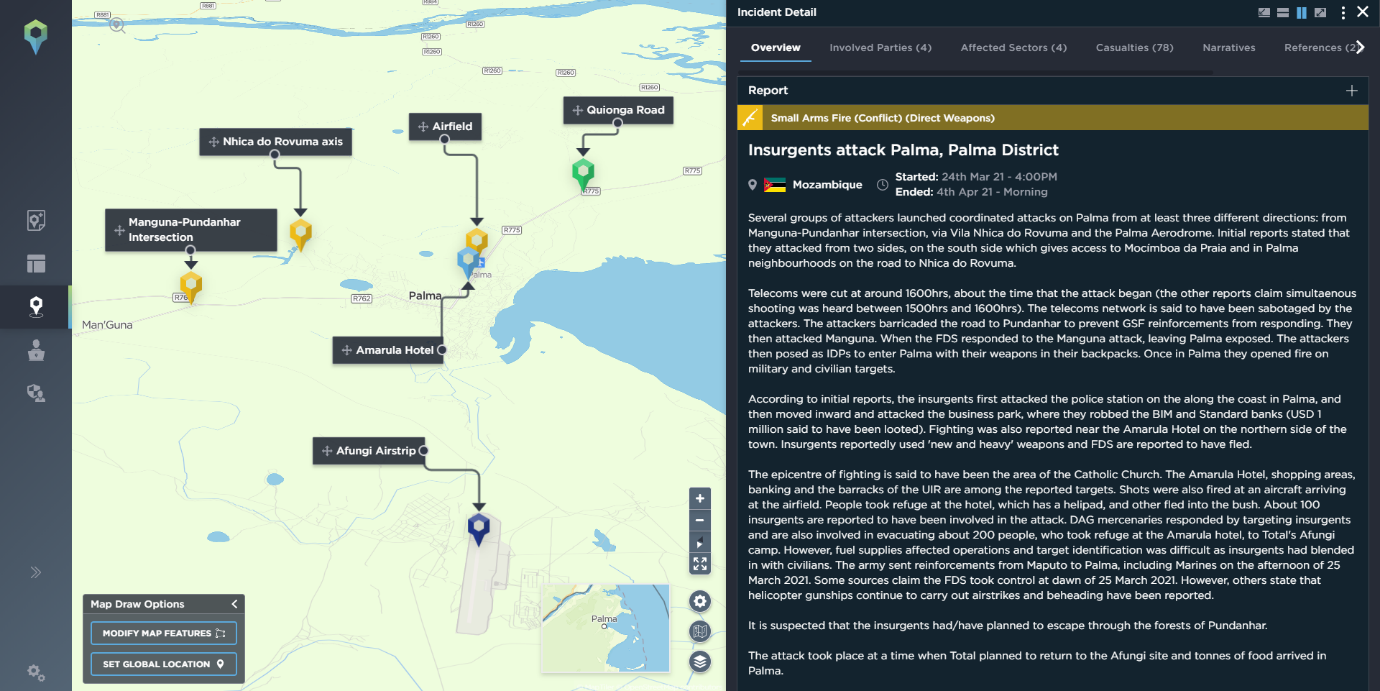

SIGACTS (Significant Activities) carried out by insurgents in northern Mozambique [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

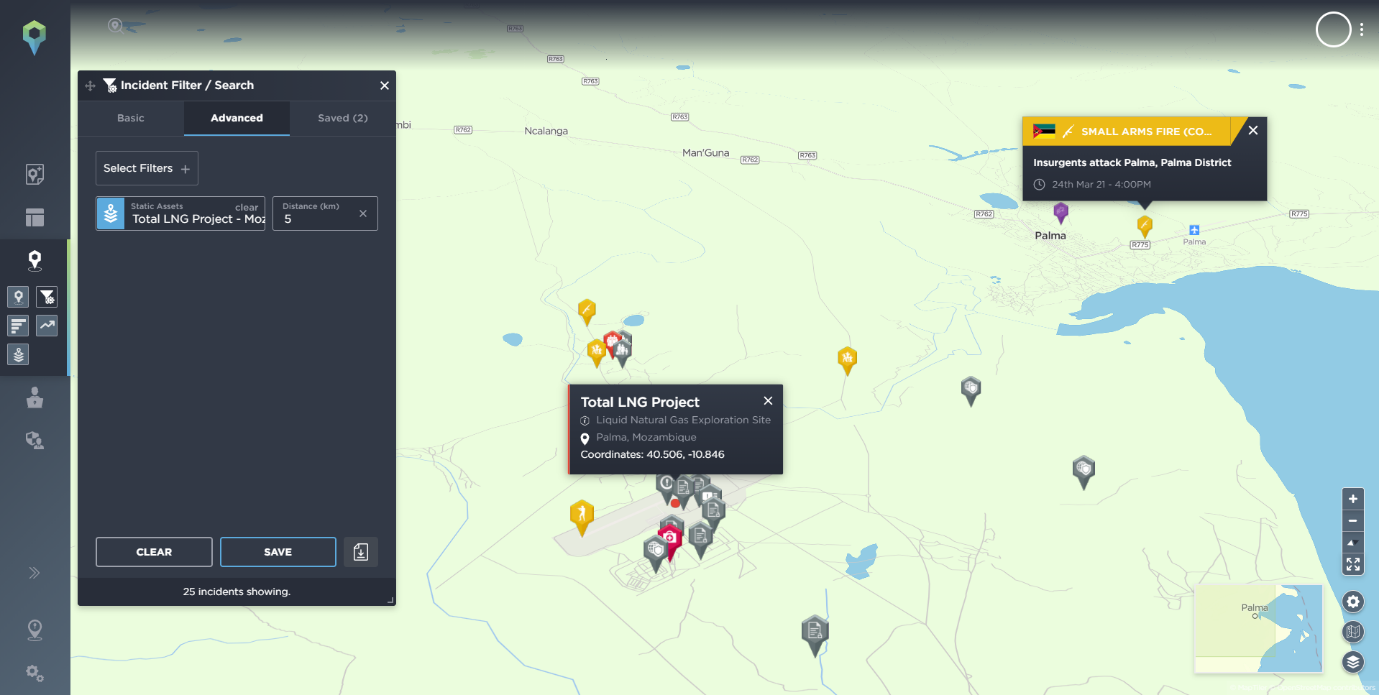

The terror attack on Palma, Mozambique in March 2021 [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

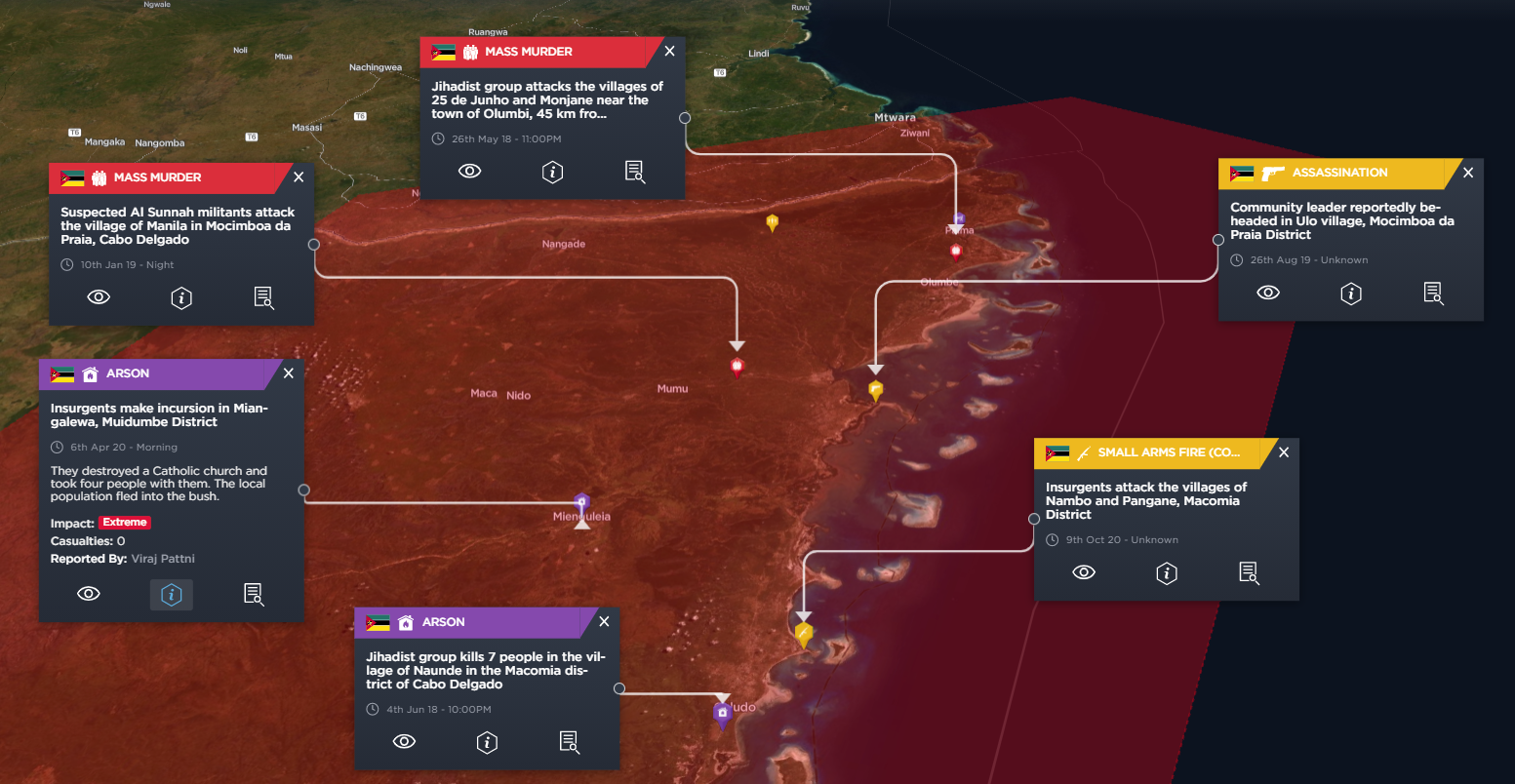

Small Arms Fire clashes in Northern Mozambique [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Attacks carried out by Jihadists in Northern Mozambique demonstrating the ethnic dimension of the conflict [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Recent Developments

Terrorist attacks in Mozambique in 2021 [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Insurgents have also been abducting IDPs, mainly off the coast of Macomia District, as well as at Ilha Makaloe, and mounting attacks on vessels carrying IDPs and fishermen.

The electricity supply to Muidumbe, Mueda, Nangade, Palma and Mocimboa da Praia districts is yet to be restored with power lines down and the Awasse sub-station damaged by insurgents on September 2020. Insurgents remain in control of Awasse, also a strategically important intersection, despite offensives launched in the area most recently in December 2020 and February 2021.

In recent weeks, a new force of well-trained and equipped units have been conducting a number of offensives aimed at regaining control of three key roads: Mueda-Awasse-Mocimboa road, Mueda-Macomia road and Mueda-Nangade-Palma road. A camp with 30 insurgents was attacked by security forces, while the FDS reportedly also regained control of Diaca and achieved some success elsewhere in Muidumbe District. While an offensive resulted in the FDS regaining control of Namacande, Nangunde and Ntchinga villages with the help of SA-341 Gazelle (reportedly used for the first time according to a Cabo Ligado report), Mi-8 helicopters and local militia, the FDS withdrew from Namacande after resupply requested by commanders on the ground was not provided.

Despite FDS successes against ASWJ, the group remains resilient, in part aided by strained resources.

Map of the DUAT/LNG site [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Response and foreign intervention

Map showing counter-terrorism-related operations and arrests. ASWJ bases have been attacked in Pundanhar, Narere, Cajembe, Mbau, Nkonga and in the Awasse vicinity. [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

The Minister of Interior admitted the existence of mercenaries, in October 2020, and that the country does not possess the capacity to fight ASWJ alone. The police, army and navy lack adequate equipment, logistical capabilities and the necessary training to counteract ASWJ. The provincial police commander recently complained about the lack of communications equipment, transportation, and adequate pay. Additionally, delayed salaries, food supplies, poor troop rotation and attacks by ASWJ have contributed to low morale. Worryingly, reports have surfaced recently of desertions among the ranks of the armed forces (FADM).

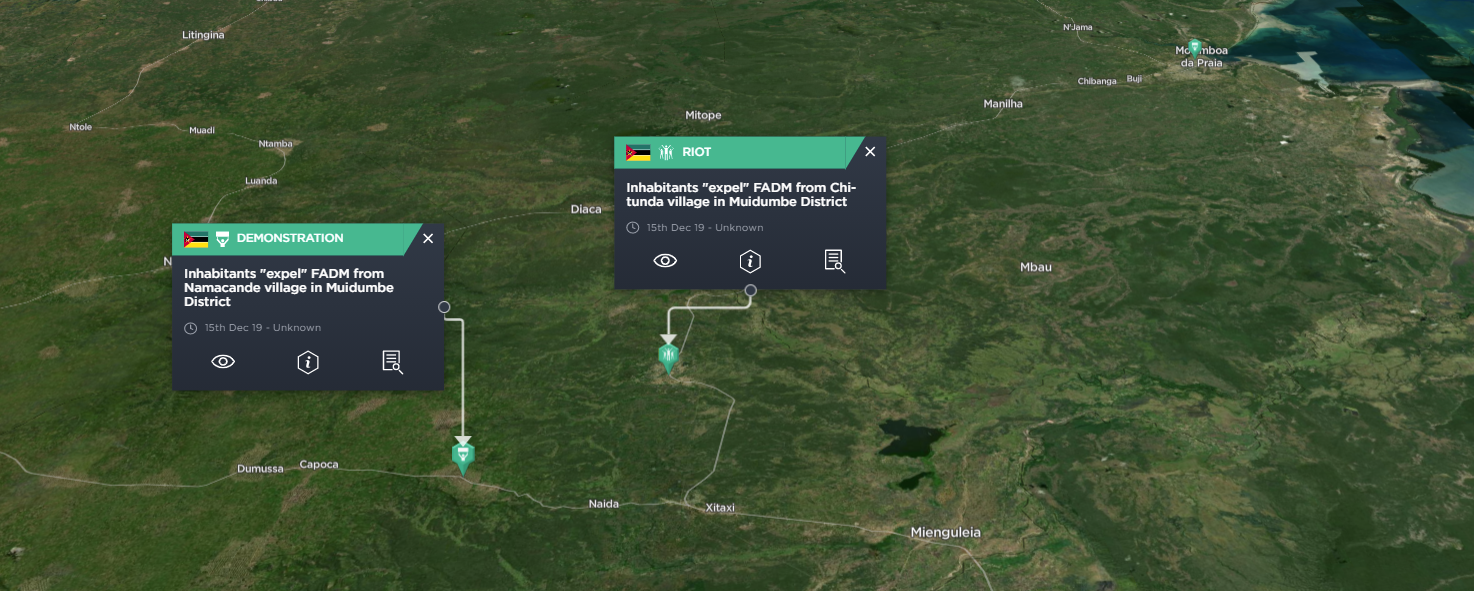

Abuses committed by the FDS against the civilian population are also likely to have hindered cooperation and eroded trust in the FDS and aided insurgents with intelligence gathering. The failure to stop attacks has also resulted in protests against the FDS, as was the case in Muidumbe District in December 2019. If continued insecurity persists, or particular ethnic groups feel they are targeted by the FDS, self-defence groups, so far most active in Nangade and Mueda District, could play a larger role or lead many to join the insurgency in Mozambique. Along with other implications, increased self-defence group activity in the operational theatre could risk compromising the state’s monopoly on the use of violence.

Protesters ‘expelled’ Mozambique’s armed forces from villages in Muidumbe District in 2019 [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

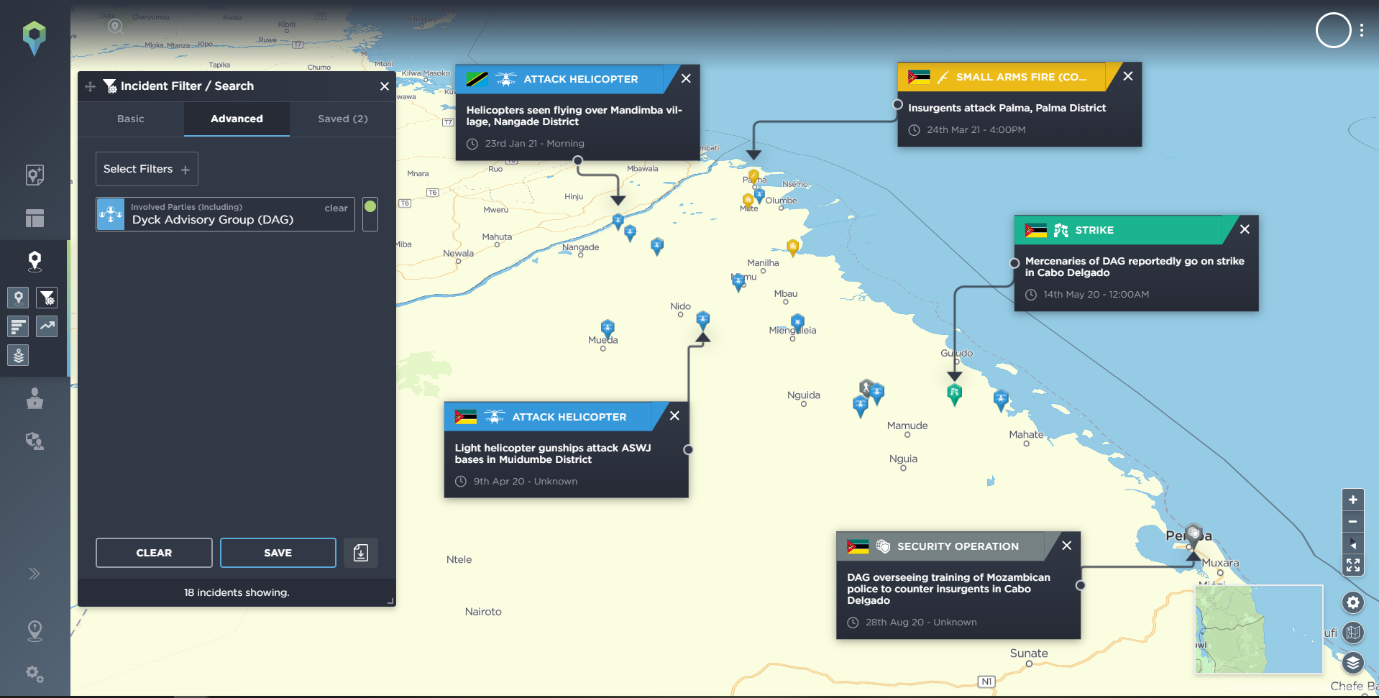

While mercenaries such as Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) have provided vital aerial support to ground troops, DAG have relied on Gazelle, Alouette III and Jet Ranger helicopters fitted with W85 heavy and Type 80 general purpose machineguns, AGS-17 30 mm automatic grenade launchers and improvised gas cannister based “barrel bombs”. During missions in Macomia, Mocimboa da Praia and most recently Palma, their helicopters had to withdraw due to low fuel reserves or fuel shortages, consequently reducing aerial presence. Additionally, attackers wearing military uniforms or mixing with civilians made it difficult to distinguish combatant from non-combatant. Before DAG’s involvement, Russia’s Wagner group also deployed to support the FDS. However, they withdrew after suffering a series of setbacks partly due to the nature of the terrain and ineffective equipment. Soldiers were are also reportedly not accustomed to fighting in the terrain and tension was reported between the FDS and Russian mercenaries after the failure of several military operations. Their withdrawal raised questions as to why they were handed the contract.

Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) mercenaries have been contracted by the Mozambique government to assist in the fight against insurgents [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Thus far, the Mozambique government has shown reluctance to accepting foreign military aid, although this position has slightly shifted. In early December 2020, before a series of attacks around Palma and the Afungi site, the spokesperson for the Council of Ministers said that military support is out of the question. However, on October 2020, the government asked the European Union (EU) for logistical support and specialised training of government forces, and a dozen U.S. Special Forces recently completed the two-month training of Mozambican marines, now ready to go into combat. Portugal has also sent 60 Special Forces to train Mozambican marines and commandos, while French President Emmanuel Macron has also expressed a readiness to provide military support if requested by the government. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) technical assessment mission proposed, after a week-long visit in April 2021, intervention of a force of 2,916 soldiers including infantry, two special forces squadrons, two attack helicopters, two armed helicopters, two surface patrol ships, one submarine, one maritime surveillance aircraft as well as other logistical support aircraft, equipment and personnel. The SADC will reconvene on June 2021 where it is hoped President Nyusi will allow an SADC force to intervene in the country. Any intervention will require the approval of all 16 SADC member states. Tanzania, meanwhile, has distanced itself from any intervention.

Possible Scenarios

ASWJ expand their geographical presence

ASWJ, in the long-term, could expand their area of operation to other districts in Cabo Delgado and provinces such as Nampula and Niassa particularly if they come under pressure from COIN operations. Indeed, ISS report that in August 2017, armed men wearing robes attacked a police station in Mogovolas district, capturing firearms in the process, and suggest this may have been the first attack carried out the group. While motivations for the attack are unknown, it could be an indication of the rejection of the state and if this is the case, then ASWJ could tap into such sentiments to expand the group in other provinces. While the group has already carried out attacks in Tanzania, the group could also increase its operation tempo in the county and/or use it as a safe haven to plan attacks. Foreign fighters could also enable the group to grow in influence in the region and conduct attacks thousands of miles from their AOO (Area of Operation). Prime Minister Carlos Agostinho do Rosário warned in April 2021 that the group may be expanding their cells across the country. The group has already threatened to open a “fighting front” in South Africa if the country intervenes in Mozambique. South Africa’s elite police unit claims that there are South Africans involved in fighting and that some have provided or are still providing the group with financial and material support.

Attacks grow in sophistication

In contrast to other VEOs (violent extremist organisation) in Africa, ASWJ do not currently possess the capability to launch devastating attacks using IEDs or suicide attacks. While attacks have been claimed by ISIS, there is no indication yet of a transfer of skills and knowledge pertaining to the assembly of IEDs, for example, that would be expected with links to a VEO such as ISIS whose branches regularly use such devices. However, the diverse range of languages spoken within the group and that it is operating in a region with jihadist networks, and in close proximity to groups such as the ADF (Allied Democratic Forces) in DR Congo and Al Shabaab in Somalia, means that it is likely that deeper knowledge and skill transfer will occur. Insurgents could also take advantage of weak territorial, coastal, and maritime law enforcement capabilities to attack shipping vessels potentially engaging in kidnap for ransom to generate revenue. There are reports the group has used kidnap and ransom: ransoms are reported to have been demanded for some kidnap victims, including foreign nationals kidnapped during the attack on Palma on March 2021, where insurgents are also reported to have hijacked two vessels, a potential sign of things to come.

Attacks on cities

In attacking major towns and having carried out simultaneous attacks in Cabo Delgado Province, ASWJ has consistently displayed high levels of planning, coordination, manpower and capabilities. Concerns have been raised over possible attacks on Pemba, the capital of Cabo Delgado Province. However, the group has not demonstrated the ability to attack an urban area the size of Pemba, a city with a population about three times that of Palma. At its current form, any attacks or incursions on Pemba could involve the use of the Inghimasi tactic and/or the sabotage of infrastructure or even attack by sea. Analysis of attacks carried out by the group show that it has consistently targeted critical infrastructure, and made use of informants and infiltration to carry out attacks. In the short to medium term, attacks on Mueda, home to a key military base, and Nangade, where the group has encountered resistance from local militias, are more likely.

Future of the LNG project

Total Energy’s natural gas project in northern Mozambique [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Threat intelligence is key to managing and maintaining business continuity during these uncertain times. Reliable, fact-checked data can provide you with an advantage not only when responding to unrest, but in terms of spotting potential actions and identifying trends through indicators and warnings. Intelligence Fusion will continue to provide timely alerts on the ongoing fighting as well as report on the wider impacts of the insurgency in Mozambique.

Stay informed on the issues facing the extraction industry around the world, as well as wider weekly and monthly incident reports, by signing up to our mailing list.

For more information or to take a closer look at the data that supports our analysis, access a free trial of Intelligence Fusion by speaking to a member of our team today.

References

https://www.iese.ac.mz/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/cadernos_17eng.pdf

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17531055.2020.1789271

https://allafrica.com/stories/202105060770.html

http://www.dailynews.gov.bw/news-details.php?nid=62463

https://allafrica.com/stories/202006230761.html

https://www.macaubusiness.com/mozambique-kidnapped-women-return-tell-of-insurgent-organisation/

https://www.portaldeangola.com/2017/10/09/jovens-radicais-sonham-com-califado-em-mocimboa-da-praia/

https://www.dw.com/pt-002/ataque-em-moc%C3%ADmboa-da-praia-ter%C3%A1-sido-caso-isolado/a-40977442

https://www.oecd.org/dev/36741703.pdf

https://www.opais.co.mz/homens-armados-entregamse-as-autoridades-em-mocimboa-da-praia/

https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/751/materials/summaries/individual/aboud-rogo-mohammed

https://macua.blogs.com/moambique_para_todos/2021/05/deser%C3%A7%C3%B5es-entre-as-fadm.html

https://www.caboligado.com/reports/cabo-ligado-weekly-10-23-may-2021

https://www.caboligado.com/reports/cabo-ligado-weekly-24-30-may-2021